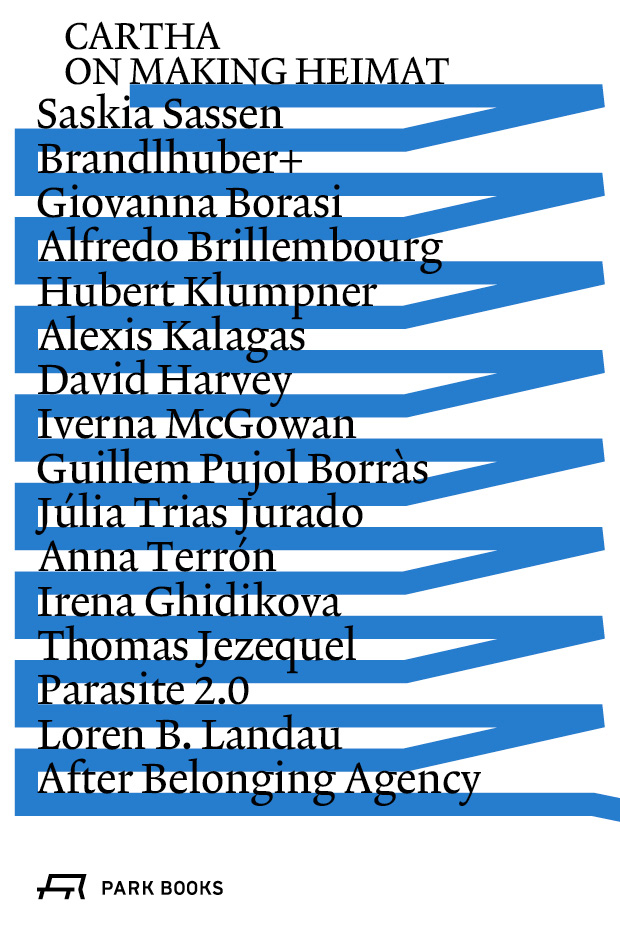

A SPECIAL ISSUE ON THE GERMAN PAVILION AT THE 15TH INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURE EXHIBITION LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

CARTHA

This is the true nature of home – it is the place of peace: the shelters, not only from all injury, but from all terror, doubt and division…” John Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies We want to focus on what we have in common rather than on what differentiates us from each other. Tzvetan Todorov’s […]

This is the true nature of home – it is the place of peace: the shelters, not only from all injury, but from all terror, doubt and division…”

John Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies

We want to focus on what we have in common rather than on what differentiates us from each other. Tzvetan Todorov’s definition of otherness understood “as the relationship between people of different cultures and countries, as well as the otherness that binds you to the closest human beings”, implies that the dependency relationships of human beings are constitutive of human identity, that the true human nature resides in the common, not in the special, that which makes us different from each other is, at its limit, accidental.

With this in mind, the relation between acknowledging others and the acknowledging of oneself as part of the same whole becomes clear. Thus, if others are not at home, how can we be?

When approaching the first edition of CARTHA on Making Heimat, it was our will to extend this notion to the contributions in order to profit from their multidisciplinary background and their diverse views on the questions raised by the German representation. With this second edition we wanted to expand on this, to add a precise set of contributions that would contribute to a better understanding of the topic at hand.

The copies displayed at the German Pavilion served its purpose within the context of the Venice Biennale but it also made us realise the potential in the extension of the discussion of its content beyond the physical and temporal limits of the Biennale.

This publication reflects on migration movements and their consequences, from the perspective of otherness. Whilst editing it, we came to understand that one valid way of creating the space -not only physical but also emotional and conceptual- where “Heimat” can be built, is through the acknowledgement and the awareness of others and the relations that bind us.

Oliver Elser

Peter Cachola Schmal

Anna Scheuermann

Making Heimat is growing. We feel delighted that our exhibition at the German Pavilion in Venice has inspired Cartha to do this special edition. But how did it all getting started? The idea for Germany’s contribution to the Architecture Biennale originated during the turbulent weeks of autumn 2015 when, every day, thousands of refugees were […]

Making Heimat is growing. We feel delighted that our exhibition at the German Pavilion in Venice has inspired Cartha to do this special edition. But how did it all getting started?

The idea for Germany’s contribution to the Architecture Biennale originated during the turbulent weeks of autumn 2015 when, every day, thousands of refugees were arriving at stations and while the German Chancellor was sticking with an iron will to a policy of no upper limit for the number of refugees coming into the country. “Wir schaffen das” (We can do it). This unexpected openness became the Leitmotiv for the German Pavilion at the Biennale. Months later, the borders are again closed. By contrast, the German Pavilion is open. Four large new openings have been cut into the heritage listed façade.

Together with Something Fantastic – a Berlin based design office – and Clemens Kusch – an architect whose practice has for years now supervised all building and renovation work at the German Pavilion – we begin to draw up detailed plans for the location and size of the openings, plus the tender documents. The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety is persuaded to back the alterations. In official channels, everything is running like clockwork. Once the Milan consul hands over building application to the German Embassy in Rome, from where it goes to the Foreign Office, who asks the Construction Ministry what on earth is going on, it takes only a few days before two federal ministries have agreed to sign it off. The German Pavilion is to be opened up.

Openness or building site?

What precise message should the open pavilion try to convey? The Ministry’s take on it is: since 2015, Germany has become a gigantic building site. By contrast, DAM and Something Fantastic feel the pavilion represents the friendly, open attitude towards all those streaming into Germany. Borders are open, walls are permeable – the country and the pavilion are no longer what they used to be. At the same time, the openings should not just reflect the current political situation, nor should they be a government-built statement sanctioning Merkel’s strategy. The open pavilion should become a meeting place. It should no longer simply be an exhibition space, but a public space, a place flooded with light that draws visitors in. A space that scoops up the lagoon view through these huge openings, and brings it into the otherwise disconnected business of exhibition-making in the Giardini.

Had this idea been proposed for an Art Biennale, one might have said: ‘OK, fine, let’s leave it at that – mission fulfilled’. Would it not indeed suffice to cut open a heritage-listed building that still carries the burden of its Nazi past as well as all attempts at dealing that period, then deem it to be a huge sculpture, and simply leave it empty? Might that be a logical move? Or would such rigorous idealism just be terribly German? At an Art Biennale, an artist would need to throw their full weight behind such a radical gesture. In the Making Heimat project, Something Fantastic took on the role of the artist.

Ethnic networks instead of ghettos!

The Arrival City concept was there right from the start of the Biennale project. But opening up the pavilion was still a long way off. The refugee situation had by no means reached such epic proportions when DAM – with Doug Saunders – began their application process for the German pavilion in June 2015. By October 2015 the world had changed. The original idea of using Doug Sander’s book as a springboard to examine what makes a successful Arrival City, and seek out Arrival Cities in Germany, had become eclipsed by the debate about the reception of refugees. However, to talk about Germany as a country of immigrants, rather than discuss the role that architecture and urban planning might now play in helping to cope with the refugee crisis, would have been absurd. Under these circumstances, with so much palpable curiosity and enthusiasm, yet scepticism too, simply leaving the pavilion empty was clearly not an option either. As a result, the exhibition Making Heimat focused on two main issues. The first chapter showcases contemporary housing projects for refugees and in March 2016 a databank, which is continually updated, was set up on the website: makingheimat.de. The second chapter on-site in Venice addresses the question of what actually happens once a refugee becomes an immigrant. First studies indicate that when refugees leave their first officially assigned locality to move to cities, they tend to move to an Arrival City in which their fellow countrymen live. Rather than regarding these Arrival Cities as posing a danger, or as problem zones, ghettos or parallel societies, Doug Sander’s book argues for a shift in perspective, regarding these places instead as offering immigrants an opportunity to start building a new life for themselves within existing immigrant networks.

The pavilion clearly bore the marks of those particular circumstances in autumn 2015, even though – with the closure of the Balkan route, and an agreement with Turkey concerning refugees – the political framework had already changed before the Biennale opened. As a result, by the time the pavilion finally opened to the public its overriding message had already become past history.

The pavilion was open but the borders were already closed. A strange situation.

During the Venice days, the space became a place for political manifestations that were banned elsewhere. For instance, a group of french activists presented their magazine at the German Pavilion because they were not allowed to do this in the nearby pavilion of France. So in it is best moments the pavilion was a platform. It was even taken as a starting point for this special issue of Cartha.

We appreciate the selection of authors for this magazine. It might act as an intellectual backdrop for the more pragmatic, more ‘reporting’ approach of our Venice exhibition.

When we write down these lines, Making Heimat has come to Frankfurt. Coming back home, we took over a different task. Offenbach, an arrival city close to Frankfurt, is now in the focus. It is good to welcome those migrants, which were addressed as abstract subjects before, in our museum. At home we feel a different spirit. From the overview we have moved to the details of the everyday business of living together. The discussion can move on. Cartha and this special issue are a great contribution to this.

Pablo Garrido Arnaiz

Guillem Pujol Borràs

Júlia Trias Jurado

You have theorized about the incapacity of the term “migration” to define the current migration phenomena, incapable to grasp the nuances and complexities this entails. What could be a more appropriate way to define or refer to these current phenomena? There is a new type of migrant that is emerging from what I think […]

There is a new type of migrant that is emerging from what I think of as a massive loss of habitat –this is a migrant who has no home that he/she leaves behind. This is a new type of refugee resulting from destructive forms of economic development and from climate change1.

Extreme violence is one key condition explaining these migrations. But so are thirty years of international development policies that have left much land dead (due to mining, land grabs, plantation agriculture) and expelled whole communities from their habitats2. Moving to the slums of large cities has increasingly become the last option, and for those who can afford it, migration. This multi-decade history of destructions and expulsions has reached extreme levels made visible in vast stretches of land and water bodies that are now dead. At least some of the localized wars and conflicts arise from these destructions, in a sort of ‘fight for habitat’ and climate change further reduces livable ground. These are all issues I develop at length in “Expulsions”. (published in German by Fisher Verlag – 2015)

Think of these migrants as usually well educated and trained, with skills, and the will to make a new life, precisely because there is no home to go back to as home is now a warzone, a mine, a plantation, a desert, a flooded plain. Think of these migrants as having the will to ‘make’, that being to make an economy, make a culture, make a sociality. And then think of abandoned or semi-abandoned localities in Germany, and remember those migrants who have been offered to live in half empty or almost completely empty villages, and how they managed to make… yes, an economy, a culture, a sociality…3

What I described above is one way. This would be one option where architects, builders, water engineers, agricultural experts could help make it happen, and it would all add to the region, the country. I am also reminded of a group of techies, Spaniards, in one of Spain’s major cities, I think it was Barcelona, who lost their jobs and decided to go into the arid mountains, to an abandoned village. It took them two years and then they had a live economy, selling rural products to …guess what, the big cities in Spain.

What we do not want is what is happening increasingly in major cities – which is the buying of urban land by major corporations4,5.

Immigrants, with their capacity to make neighborhood economies, can be a major plus to resist this, though if a big firm really wants a plot of land they are ready for just about everything.

When we speak of urban environments –and not the under-inhabited environments I’ve described above — the picture becomes more complex. But one key fact that we know from the experience of so many immigrants across the world – from New York, to Nairobi, to Tokyo, is that immigrants, if allowed to live a normal life (not be secluded in camps) make jobs. Immigrants are famous for this: they make jobs, and if you live in any big German city you know that. The issue is the dying cities due to deindustrialization where jobs are being lost, and the residents feel that if immigrants came they would take away the few jobs that are left. There are mostly no immigrants in these cities , so its residents just know the fear of jobs, not what immigrants can do. They have a hard time imagining (and one can understand this) that if immigrants came, they would not take away jobs, because all they know is that the jobs keep disappearing from their cities. But if immigrants were given a chance to come, most of them would make jobs.

Public spaces, especially streets, are critical and I have a whole project on the street. I think of the street as an indeterminate space where even those who are not fully accepted can feel comfortable. The piazza, the boulevard, are overdetermined spaces, and many newcomers, especially if immigrants and refugees, can easily feel that it is too overdetermined and really, even if public, are not “their” Piazza or “their” boulevard. So alienation can set in. I am doing a project on this, a big project in Paris, supported by the College du Monde, a newly invented organization by Michel Wievorka which is quite exciting. And my husband, Richard Sennett is doing a parallel project there on Theatrum Mundi. So, back to your question, it has to be a mix of design, yes, but also the cultural, very broadly understood, background6.

Housing should also be a place for productive work – it cannot be reduced to sleeping and eating The work that Teddy Cruz has done on this type of housing and neighborhood on the Mexico-US border is interesting. The larger setting or neighborhood where the housing is built, should have streets that are public spaces, should have broad sidewalks and small squares where people mix, should have authorization for holding events, for making music, for teaching each other crafts and how to play instruments, so that it would draw all ages and locals and foreigners.

I think what should happen is what I have been describing above and small numbers matter, so multiple little squares and centers. This allows both immigrants to keep their culture, but also to share that culture and begin to share in the host culture, it is not a case of ‘either/or’.

De facto cities have had to engage in more local control because so much of our economies and hence politics are being urbanized. And yes, some of this authority should be formalized because that would justify central governments passing on more resources to cities.

As I said earlier, we need to bring in the rural, especially in the form of under-inhabited villages, and even completely abandoned villages. If support for infrastructures can be mobilized, there will be significant numbers of migrants who will take on such possibilities and make it work.

Definitely: we have all heard from the recent flows of desperate people coming from the war zones that having their phones mattered a lot for a series of reasons, however much more could be done. All the items I have described above, that I think matter for incorporating migrants, should have a digital platform that can then also expand across a country and serve to help and inform on situations where matters are not going well. I have worked on some of this for the case of low-income neighborhoods in major cities in the US. Also interesting is the notion of open-sourcing the neighborhood7.

I think I have answered this above, but let me add also that the migrant should be allowed to keep parts of her culture and should be invited to learn about local cultures for example in local weekend street or small square events, where small groups of locals and foreigners can actually mix. To help this there should be a central activity that can be share like music making, where everybody brings an instrument, including a pot that can be a drum, or your voice, is often something that works well. Events around cooking is another example when understood as cooking plus talking about food, demonstrating to each other, and above all-eating together. Participants should be old, young, both men and women and should always be in small numbers. When the 2000 crisis hit in Argentina, I remember in Buenos Aires fired workers re-entered abandoned factories and opened them up to the community8. They kept part of the space for working and selling what they had done before under a boss, and the rest of the space was for the community where they would meet and cook collectively etc., and it worked!

Arno Brandlhuber

The text Property Obliges is based on an interview as part of the ongoing film project Legislating Architecture, by Brandlhuber+ Christopher Roth. A discussion on the openness of society, is always about the accessibility of space for people — a priori. This inevitably leads to the debate about the right of usage and in […]

The text Property Obliges is based on an interview as part of the ongoing film project Legislating Architecture, by Brandlhuber+ Christopher Roth.

A discussion on the openness of society, is always about the accessibility of space for people — a priori.

This inevitably leads to the debate about the right of usage and in our current setting to the question of „who owns the ground?”.

The issue of appropriation of ground is basic for all forms of migration, including our own.

Thus the question of land ownership is the starting point in the possible transition to an open city, country and Society.

-14 Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany / sentence 2 Property entails obligations. Its use shall also serve the public good (1)

The German Federal Constitutional Court expresses its stance on Article 14 of the Basic Law in a decree from January, 12th 1967. It refers to the protocols of the Parliamentary Council of 1948, which clearly show that the second sentence of Article 14 of the Basic Law was designed with the matter of landed property in mind. Accordingly, regarding questions of ownership of land and property, the Federal Constitutional Court is obliged to the interests of the general public to a far greater extent than regarding other property assets. The fact that the use of land is unavoidable and indispensable, shall prohibit it from being left to the inestimable free play of market forces and to the discretion of the individual. (2)

Subsequently, thoughts from a dialogue between Dr. Hans-Jochen Vogel and Arno Brandlhuber should provide an impulse for reflection on this topic. Hans-Jochen Vogel (SPD, Social Democratic Party) former Mayor of Munich (1960-72), Federal Minister for Regional Planning, Building and Urban Development (1972-74), Federal Minister of Justice (1974-81) and Governing Mayor of Berlin (1981), inter alia focuses on questions of landownership and their direct link to the German Basic Law and the levy of unjustified land assets. Vogel envisions a land management which enforces ecological and social objectives in municipal and regional spatial planning. (3)

Article 14 discloses the still unresolved tension between the rule of law and the welfare state. The social injustices which are caused by the rapid rise of land prices to a significant degree, affect us all. According to Vogel, in Munich, the land price has increased by 36.000 per cent over the last fifty years. Consequently, therefore, he not only raises the question of affordable housing but also of unpredictable expenses for municipalities when buying land for necessary infrastructure and building projects.

The profiteers of this upward spiral are landowners, who themselves do not provide any services like investments in reutilization or infrastructure. Profits from land ownership largely derive from the growing demand for land or from taxpayers’ investments in infrastructure. Vogel does not see any justification for the enormous revenues of this small group of fortunate landowners.

In this respect Hans-Jochen Vogel provides a first approach to solve the problem of steadily increasing land prices and the privatization of land,

by suggesting the division of land ownership rights into usage-rights and freehold- rights: “The existing ownership of land is divided into usage- and freehold property — whereby the latter would belong to the community. It establishes a contractual right of usage, which can be terminated or granted only for a limited time and regulates the nature and duration of the use, as well as the usage-fee. If this is not in conflict with communal interests, the usage-right is to be awarded by public tender. “(3)

This new property management would restore the flexibility needed to meet the challenges we are facing today. A dynamic urban development that is beneficial to all groups of society, first and foremost requires a mobile land management that can adapt to social realities.

—

The idea of a new land management was a recurring matter for Social Democrats as well as for other parties. In 1989, this important debate became a topic of political discussion and part of Berlin’s SPD’s policy program. Since then, however, the discussion about a potential reform has died down, and disappeared completely from the political debate.

Francisco Moura Veiga

In the Journeys exhibition with the great title, How Travelling Fruits, Ideas and Buildings Rearrange our Environment, you approach the topic of migration as something inherent to our nature. Migration is, after all, a constant in human history. My question would be, how do you perceive the current situation regarding migration in the Mediterranean Sea? […]

I curated this show in 2010, and I think the context was very different then. This sense of emergency was maybe already present, especially in the Mediterranean area, but it was years before we came to have a kind of critical flow at this pace. The idea was to look at migration as an inherent part of human history. When I decided to work on this topic, I realized there have been many exhibitions and research projects that dealt with the flow of people: how people move from one place to another, how many immigrants a country has and so on. Beyond the basic fact that people move, I was more interested in what the tangible consequences of these displacements would be with respect to architecture and the built environment. What are the traces and the inevitable cultural changes that this movement implies? More than responding to the question, “How do we deal with this emergency?” the exhibition addressed some key aspects of what migration means and, more specifically, the idea of people moving with cultural baggage like techniques of building that a community brings from one culture to another. How do these techniques influence the new place and what is the impact in the long term? I think it is also important to mention that this show took place in the context of Canada, where migration has a certain meaning. It is very different from the European situation. And it is very different from the United States, where there is the idea of the melting pot, where, in the end, everybody becomes American and the previous culture is set aside. In Canada, the idea is that your own culture stays with you. Even if you enter into a set of Canadian values, your own culture and identity are still very much respected.

Today we realize that Europe is the destination for many migrants. The amount of people arriving is critical. How then are these people integrated and helped? How do we deal with all of these questions? So the show—and the title alludes to this—tried not to be specific to a certain time or certain flows of migrations, but to tackle the more general and universal issues caused by these flows. Quite deliberately, a human body was not represented in the exhibition. I was always referring, in a metaphorical way or in an abstract way, to ideas moving through building techniques, ideas of architecture, or even fruits and vegetables. Basically the intention was to address these topics, referring always to our human history, but never really to relate directly to a certain group of people or to a specific set of cultures. For me, it was very much about, for example, people moving from Italy to Vermont because they were particularly skilled in working with granite. And they changed the culture in the area around Barre, Vermont: many of the migrants were anarchists, and in Vermont today there are still many institutions that are very much left leaning. This development can be traced to this period of migration. So it was not just about these Italians coming to Vermont with their expertise in carving; they also brought their political ideas that had an influence in certain communities.

So if I return to your question about what is happening today, I think the conditions are very different. I feel we are facing an emergency. We have to deal with a situation that we perhaps aren’t prepared for and do not have good answers for. It’s tempting to propose an immediate answer to respond to what is happening today. In addition, we have a Europe that doesn’t have a unified idea of how to deal with issues of migration. In the Mediterranean, historically populations coexist with flows and continuous cultural exchanges. For example, the story I wrote for the book that accompanies the exhibition—which is not a series of essays or academic case studies but rather fictional writings—I focused on Mazara del Vallo, a small town in Sicily where the language is mixed with Arabic due to centuries of exchange with Tunisia. Italians fished in Tunisian waters, and vice versa. This has changed the town’s culture and has also left traces in the built environment and structure of the town, where the main core has distinct Arab characteristics. I think there is a very different approach in countries that are at the edge of the Mediterranean. I would say that in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, there is an understanding of migration that is different from the understanding of the issue elsewhere in Europe. I think the emergency now is happening in a Europe that is certainly not unified in its approach; each country deals with local policies in a distinct way.

As I said I think now we are treating situations like this as emergencies. For immigrants, there is a city where they first arrive, where they are helped at the first level. But then there is no clear vision of a future and how they can be integrated into society. There are also many people who arrive in a country but actually want to reach another European country. Can we say these people are choosing to migrate to this first country as if they wanted to stay, or are they just escaping? This is just the first place they land; any safe place is fine from this perspective.

At the CCA last year, we had a show on two projects by Álvaro Siza from the 1980s that address this question of the integration of migrants, in the context of Berlin and The Hague. Siza remarked that the Dutch government asked him to design two different types of housing: one for Dutch people and one for Turkish migrants. But he refused to comply with this, as he thought it was a sign of a double segregation. The immigrants would never really be integrated if the attitude is, “You are Turkish, so you live in an apartment that is tailored—supposedly—to your culture.” The migrants will always be different because they will never have the opportunity to understand what living in the Netherlands is really like. I have to say that I find this idea of defining a specific architecture or a specific part of the city as dedicated to an incoming population extremely problematic in the long term. I understand there is an emergency—all these people have to live somewhere—but I don’t think is the way to solve the problem.

In the Journeys exhibition we also had an example that focused on a Dutch urban context: the Bijlmermeer, a modern neighbourhood of Amsterdam that promised a very pleasant life. But when in the 1970s the people of Suriname (a former colony of the Netherlands) were offered Dutch passports and the possibility to move to the Netherlands, there was a sudden migration to Amsterdam. As the government didn’t really know where to put all these people, the Bijlmermeer became an immediate answer: it transformed very quickly from a modern, white, middle-class neighbourhood to a Surinamese ghetto. It is interesting to see how this community used Bloemenoord—a modern building in the Bijlmermeer with a structure similar to l’Unité. The immigrants immediately started to densely occupy and use the building’s corridors for markets and other public functions. So it became an animated city. The government, preoccupied with how to deal with this kind of new ghetto, decided to impose a very precise percentage of the kind of people admitted. A maximum of 30 percent of the residents could be of foreign origin. This became a very racial program, concerning what was considered the “healthiest” percentages of different communities possible to maintain a kind of Dutch livability. It’s interesting to see how the migrants used the Bloemenoord megastructure in a very creative way (maybe even in a way that was nearer to the project’s initial intentions), but also to see how this structure transformed itself quickly into an arrival city for the migrants, pushing out the previous inhabitants.

I think it was just a bureaucratic strategy to regulate an “acceptable mix,” but I don’t think it really worked. The Bijlmermeer is now a more elitist neighbourhood again because of the quality of the apartments and so on, but there were a lot of discussions about this solution. It was in fact a very top–down experiment.

If we look at the problem from a social perspective, we could say that there is always a sort of “good intention” that covers all of these housing programs. So then the responses are similar to what the Red Cross or other similar organizations do after an earthquake. What are the immediate priorities? Giving these people a roof over their heads, for example. And so any answer is fine as long as shelter is provided. But if you start to look at this from a different perspective, if you consider the city as your problem and not just the people (let’s forget about the people for a moment), then you might find other answers and other strategies. If you look from the point of view of the city, you might ask, “What is right for the city?” The new condition is that many migrants are arriving, so most probably we have to expand city structures and we have to develop our urban system. What is the right way to do this? In the past, cities dealt with this question by adding to the existing texture, augmenting the density. I think it is important to challenge the current mindset that tends to create a set of different conditions for the newcomers; the understanding is they will stay in a temporary way. We must take the city’s point of view and imagine how to deal with this. What should be the answer? A denser urban tissue, more building, more satellite communities, or new cities? I’m not aware of any discussion of this sort these days. For me, the real question is: if this is the current situation and Europe gets these additional millions of people, how will you face this, beyond the social emergency, focusing on how the model of the city might adapt to such rapid growth? That, for me, is the interesting discussion, to take this crisis as an opportunity to change urban settlements and their structure.

First of all, I would like to draw attention to the character of the countryside nowadays, especially in Europe where it is a very urbanized place. Often it’s the place where there is a lot of work to be done and where many workers end up finding jobs. Some years ago there was an advertisement from the Minister of Internal Affairs in Italy, which tried to counteract a kind of racist, right-wing attitude. These ads showed all the things that you, as an Italian, would not have if migrants were not there to produce them. So forget about Parmesan cheese; that is produced by immigrant Sikh communities who take care of the cows. Forget about tomatoes and oranges. You would think, “This is my culture,” but in fact it’s all managed by migrants. I agree with you: we focus a lot on this very old idea that everybody moves to cities because that is where the jobs are and where there is a concentration of everything. But I think the countryside is an interesting place to look at in terms of how these immigrant communities can be integrated, how they find opportunities for work and a different kind of integration with the local communities. In this sense, there is a very interesting situation in Canada now, and I think the government has a problem with it. Many small Canadian communities have decided to invite Syrian refugees to live. So these small communities in the middle of nowhere, in the Canadian prairies, raised money to, let’s say, adopt these families. It’s a very different attitude; people, as a community, decide to welcome immigrants and confront the need to think about how to handle these people once they arrive. I gather that in the countryside, this would very much be possible. I think this could be the topic for one of the next shows at the CCA: the idea of the countryside as a place where a lot of new technologies have been developed, and where social experiments have been carried out. AMO/OMA is working on this, and in Japan there is a new tendency to consider going back to the countryside because of the growth of the aging population. It is very specific—there is virtually no migration in Japan—but the country is facing the issue of an aging population in areas that are completely abandoned because the young population wants to live in big cities and to be connected to a completely different condition. Therefore there are very interesting projects being developed now to try to understand how to bring communities and work back to the countryside. I think that, in Europe, this is not happening at the level of policy but it is happening simply because of the fact that a lot of people find jobs in the countryside. But in these cases housing and living conditions are not really addressed.

Alfredo Brillembourg

Hubert Klumpner

Alexis Kalagas

BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME Migration is a defining challenge for architects and designers today. But migration has always been at the heart of urban change. Cities are fundamentally places of opportunity – urban migrants continue to be drawn in their millions by the promise of security as well as upward mobility. As Doug […]

BRINGING IT ALL BACK HOME

Migration is a defining challenge for architects and designers today. But migration has always been at the heart of urban change. Cities are fundamentally places of opportunity – urban migrants continue to be drawn in their millions by the promise of security as well as upward mobility. As Doug Saunders has suggested, the unprecedented urbanization patterns to which we bear witness are, at their core, an epic story of human movement, set in motion by the common search for a better life. The ‘migration crisis’ that burned so brightly in the collective European consciousness for months before being overtaken by fears of violence and ‘homegrown’ terrorism represents just one chapter in this story. But far from a simple narrative of unanticipated arrivals exposing chinks in the armor of Europe’s fortress. As architects we must understand our role in the refugee ‘crisis’ in broader terms. It is a role that spans countries and continents.

A HOUSE IS NOT A HOME

In the last year, European architectural discourse and activism has been dominated by a simple humanitarian impulse – the need for fast and effective emergency shelter in cities and towns struggling to cope with an influx of newcomers. Exhibitions like Making Heimat, however, allude to more intangible questions that resist a design quick fix. What exactly makes a built environment feel like home? What material deprivation and sense of danger must be experienced to push someone to flee that home? How can a person continue to retain a sense of identity and connection to a wider community as they move in fits and starts through unfamiliar landscapes and territories? Does the process of settling in a new city – however long – necessarily lead to the establishment of a new home? And after years of conflict, destruction, and absence, is it possible to return ‘home’ and rediscover what was lost in a place that has been rendered unrecognizable?

For those engaged with the full reality of the refugee issue these are challenging questions and impossible to ignore. Rather than a linear journey from A to B, ending with successful long-term integration into a welcoming ‘host’ society, forced migration is often a circular phenomenon. Architects and designers have crucial roles to play in the places that migrants leave, the spaces through which they travel, the urban environments where they will attempt to build new homes, and the transformed places to which they may eventually return. Our forthcoming edition of SLUM Lab magazine is dedicated to this theme, and explores the way in which conflict urbanism, internal displacement camps, border fortifications, liminal settlements, informal transit camps, planned camps, detention centers, reception centers, first step housing, social housing, and various phases of post-conflict reconstruction each reveal the way built space shapes, and is reshaped by, the refugee experience.

IDENTITY AND ARCHITECTURE

At Urban-Think Tank, we have also engaged with some of these questions in our design projects. On a conceptual level, our involvement in Hello Wood’s annual design-build workshop ‘Project Village’ has explored ideas of temporariness and collectivity. Most recently, the ‘Migrant Hous(ing)’ project grew from the desire to devise a structure that was itself migrant in nature. Each individual arrived to the site with an individual unit – a series of rotating frames that could configure into a multitude of spaces based on personal need. These units had material limitations that prevented the individual from building complete solitary housing. However, as individuals began to form relationships the units transformed. Only through a collective force could they fulfill their structural potential and exert their limitless combinatorial possibilities, testing the true nature of community building. The project questioned how displaced individuals begin to establish relationships with other traveling migrants.

More concretely, our Empower Shack housing project in Cape Town is, on a basic level, a response to the long-term struggle of migrants to establish a foothold in a new city. In this case, however, the pattern in question is rural to urban, rather than the fraught cross-border route traced by refugees. In many ways, Khayelitsha is a classic ‘arrival city’. But the particularities of post-apartheid urbanism, combined with persistent barriers to effective informal settlement upgrading, mean even after 20 years most residents of our pilot site in BT-Section live in a perpetual state of tenure insecurity and spatially entrenched poverty. Pulled by family networks and pushed by the promise of a better life, the community – transplanted largely from the Eastern Cape – has found themselves disconnected from public services and employment opportunities. The ‘home’ they have forged is fragile, marginal, and rife with personal dangers and environmental risks.

The aim of Empower Shack is to develop a scalable settlement upgrading methodology that offers immediate access to dignified shelter and basic services while establishing a clear pathway to incremental formalization. The project integrates community participation, a new housing prototype, spatial planning, and urban systems that contribute to a sustainable economic model and new livelihood opportunities. Beyond meeting immediate needs, the project also has symbolic value. The post-apartheid South African constitution enshrined a ‘right of access to adequate housing’. But this bureaucratic language masks the deeper promise – an end to deliberate structural inequality and exclusion, where the idea of ‘home’ was contingent on the whims of government planners and strictly circumscribed. For refugees and internal migrants alike, the ability to integrate goes hand in hand with the ability to imagine and build a brighter future. In its fullest sense, this means the ability to participate in a city’s political, economic, and social life.

THE SPACES IN BETWEEN

As Europeans decamp en masse for beaches in Greece, Italy, France, and Spain to escape the summer heat, more migrants than ever before are dying attempting to cross the Mediterranean. In the meantime, the March resettlement deal agreed between Turkey and the European Union has seen land borders across the continent slam shut. The conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and elsewhere fuelling a persistent wave of refugees continue, but Europe is closed for business. At the opening of the Biennale in May, the world of architecture descended upon Venice under the guise of ‘reporting from the front’ – to fight ‘the battles that need to be fought’. If urbanization is ultimately a story of migration, then the frontlines of architecture have always been located along the shifting routes and in the liminal zones traversed by people seeking a new home. Whether in Central Europe or sub-Saharan Africa, architects and designers have much to offer.

Pablo Garrido Arnaiz

Guillem Pujol Borràs

Júlia Trias Jurado

The design and planning of physical urban spaces is deemed crucial prior to the arrival of new migrations. How can architecture and urban development contribute to the integration of refugees and economic migrants in arrival cities? Migrants and refugees bring with them a whole host of cultural presumptions, habits, religious beliefs and forms of […]

Migrants and refugees bring with them a whole host of cultural presumptions, habits, religious beliefs and forms of sociality (e.g. of family and kinship). While it is not the duty of any receiving country to replicate such conditions (an impossibility in any case when refugees come from multiple and very diverse backgrounds) some sensitivity has to be shown to the idea of creating footholds within an existing urban fabric for creative integration and self-management of the spaces in which people live and eventually find and create employment opportunities. There is no formula for this, but close working with migrants and refugees on the ground and coming up with experimental designs can be exciting as well as challenging work.

The theory of urbanization is an attempt to show how the laws of motion of capital and capital accumulation are involved in city building. The aim is the maximization of accumulation of capital (along with the maximization of land values and rent extractions) no matter what. The trend is to create cities for people (particularly privileged elites) to invest in and not necessarily cities for the popular classes to live in. The right to the city views this same process from the standpoint of the popular classes where the aim is to create decent living environments for all through democratic forms of governance. Obviously these two visions clash and the struggle over the right to the city ensues.

The eviction of low-income populations from whole neighborhoods in favored locations to make way for megaprojects or higher value land uses favored by financiers, developers and construction interests is almost everywhere in evidence.

I don’t see the intrusion of alternative aesthetic preferences and judgments as necessarily bad. Indeed, I find the local differentiations created through migratory movements far preferable to monotonous and boring developer urbanization. The real estate development lobby often destroys character whereas anarchists, squatters and cultural workers along with immigrants often play a role in creating a much more interesting urban fabric. It is not always so of course but here too it is the dynamics of open struggle that should be allowed to flourish.

One of the biggest unsolved and underdiscussed aspects of urbanization is the role of property markets in general and private property markets in particular in shaping urban life. I believe a great deal of effort must now be put into designing alternative property arrangements, common property regimes, and other ways of securing people’s rights in the city.

I think transnational alliances at the local scale are an excellent idea but I don’t see this supplanting relations developing at broader scales and that will certainly involve some level of interaction like that of the state.

The self-organization of refugee groups should be a priority. Assembly style self-governance would seem particularly well-adapted for such decision-making structures.

They are never “aligned” but always a productive, disruptive and potentially creative force.

The advent of a crisis of refugees and migrants creates many stresses at the same time as it offers opportunities to explore new forms of social housing, with the emphasis upon the nature of the sociality involved. Training migrants in construction so they can self-build their own communal housing would seem a good idea. Too often migration is seen as a problem whereas historically it has more often than not turned out to be a great opportunity.

I am all in favor of the kinds of explorations that improve the efficiency of movement and social provision in urban settings and the mining of big data sets and the pursuit of Smart city agendas is helpful. Unfortunately, if this is all there is then the results will be disastrous. Smart City thinking cannot get at the radical transformation of social relations and of practices required to turn our cities into eminently liveable environments in which everyone has the right to decent housing provision in decent living environments. Smart city thinking cannot challenge the habit of big capital to build cities to invest in but not to live in. Smart city thinking leads to the illusion that solutions to global poverty and environmental degradation lie in new technologies. This has never worked in the past and I see no reason why the pursuit of some techno-utopia will succeed in the future. We need a right to the city movement grounded in an anti-capitalist ethic if we are to succeed in the quest for better urban living for all.

Question the authority of received wisdom and conventional practices and make sure that the transformation of social relations in constructive ways is the central motif rather than technocratic and bureaucratic preferences.

Pablo Garrido Arnaiz

Guillem Pujol Borràs

Júlia Trias Jurado

According to the UNHCR, over 60 per cent of the world’s 19.5 million refugees and 80 per cent of 34 million Internal Displaced People (IDPs) live in urban environments. What are the main causes that underpin forced displacements? Very often the causes for internal displacement are the same as those which cause people to […]

Very often the causes for internal displacement are the same as those which cause people to flee across borders. Take Afghanistan as an example, the intensifying conflict there has taken a devastating toll on civilians. As of April 2016, a staggering 1.2 million people were displaced within the country. This is a substantial increase compared to the end of 2012, when these numbers stood at almost 500,000. In the first four months of 2016 alone, 118,000 people had fled their homes of whom approximately 80% required emergency humanitarian assistance – this is an average of nearly one thousand newly displaced people per day. Other causes can also lead to internal displacement such as economic crises, drought, famine etc. One of the challenges that IDP can face is that there is a risk of deprioritisation of responding to their plight as they are still within their own country and therefore are often not seen as obviously in need of humanitarian relief as refugee camps which are in other countries. In Afghanistan the conditions of IDPs remain woefully inadequate partly due to the governments political difficulties and to the fact that international donors have not yet put enough focus on the needs of IDPs when looking at longer term strategies for Afghanistan.

We must be very clear that when we talk about Europe there is no refugee crisis. There is a crisis of politics, policy and humanity perhaps but in terms of tangible numbers arriving there is no refugee crisis in Europe. There are currently some 20 million refugees worldwide. The vast majority are hosted in low and middle income countries, while many of the world’s wealthiest nations host the fewest and do the least. We cannot in the EU, the world’s wealthiest political bloc with a population of over 500 million people, rationally explain why 50,000 refugees remain stranded in Greece in appalling conditions, nor why the resettlement figures into the EU remain so painfully low. All this is to say that the most challenging thing for Amnesty International in this context is the lack of political leadership. Mainstream political leaders, also at EU level, are pandering to extremists and trying to support the idea that there are no other options left other than to abandon international obligations and damn millions of people to misery.

Earlier this year Amnesty International conducted the Refugees Welcome Index which ranked 27 countries across all continents based on people’s willingness to let refugees live in their countries, towns, neighbourhoods and homes. The results were staggering with four in five people saying that they would welcome refugees to their country. It seemed that UK and Australian governments were more out of touch than any other leaders globally: an astonishing 87% of British people and 85% of Australians are ready to invite refugees into their countries, communities – even their own homes. So although we see on an individual human level inspiring levels of compassion from ordinary people, lazy political leaders instead use their own people’s lack of willingness as an excuse and even try and pin their own political failings as leaders on refugees and migrants. That is one of the largest challenges we face. Of course the sheer scale of the global crisis with more people on the move since the Second World War also means that we have to work around the clock to monitor, report on and challenge new harmful policies and practices as we see them when it comes to refugees. The scale on which to do this poses its own challenges.

This is not something we would have official commentary on.

Segregation is highly problematic, look for example at the treatment of the Roma people in many countries across Europe. In many countries (EU has opened infringement proceedings against Czech Rep. and Slovakia for this) Roma children face segregation in education. Equal access to housing and education let’s not forget are human rights. It will be vitally important also in the case of refugees and migrants that a strong anti-discrimination approach is used to ensure that segregation and the potential accompanying rights violations are avoided.

It is challenging enough for anyone to move to a new place, new culture, new language often away from networks of family and friends. Refugees have often fled very traumatising situations and therefore its desirable that they receive further assistance to help their transition such as counselling, training etc. Resettlement processes when done properly can hugely help in this way by speeding up and facilitating the transition process, this can also (depending also on whether they are allowed to work) increase the transition time to economic self-sufficiency and integration into society.

Having studied German philosophy and culture at University I understand that the German word ‘Heimat’ carries with it an emotional weight, going beyond the physical place of home to the broader psychological and cultural links to a social unit. Myself an Irish person living in Belgium, and having lived in many other countries over the past number of years I do believe indeed that a temporary Heimat is possible. Home as we say in English is where the heart is, so once you are willing to emotionally and intellectually invest in the place where you find yourself you can build a sense of Heimat in that place. Making new friendships and social connections is vital to this process I believe.

Indeed Amnesty International collaborates with a research agency to use Forensic Architecture to document and analyse breaches of international humanitarian law and human rights law. It allows us even in densely populated urban areas, for example in the case of bombings, to dissect and model dynamic events as they unfold to ensure that evidence of any international crimes are fully recorded. With regard to refugees of course it is often conflict that they are fleeing. We hope by using this evidence in the long-run that there can be justice and accountability for breaches of international humanitarian law and therefore a reduction going forward in such violations in the future which would hopefully lead to a reduction in the number of those who need to flee in the first place.

More broadly architecture can be used to remind us all of the stories of migration from our own histories or reflect current events. Often in European countries you can see a historical trace of the migration history through the buildings that still stand. Whether it’s the relics of ancient Roma buildings in northern Europe or the beautiful gardens of the Real Alcázar Palace in Spain we can see how movement of different people through generations has influenced in beautiful ways our surroundings. This should serve as a reminder that the phenomenon of people moving is as old as human history itself and perhaps challenges some of the irrationally fearful narratives we hear today on the ‘dangers’ of migration. Marvelling at architecture brought to Europe by different cultures can also serve as a positive enforcement of the richness that a more diverse society can bring.

The Convention is not outdated, it is extremely currently relevant. The problem is the lack of political will and leadership in today’s world to hold up the Conventions noble ambitions and to respect the rights that people hold under it. When we look at what is happening on the ground in Greece at the moment, we must despair. Men, women and children including elderly people, sick people and pregnant women are forced to live in circumstance that are not fit for the human person. Nothing is undermining their autonomy and empowerment more than this dehumanising treatment. It is vital that their needs and voices are directly listened to by policy makers. All too often at the moment political deals are made which will have huge consequences on peoples’ lives with little thought for what the people themselves want and need.

Of course it is human nature not to wish to live a life on hold – to be left for years on end in a camp. We all aspire for a better life. The camps unfortunately persist due in part to the lack of willingness globally to provide resettlement places to those living there. They have nowhere else to go, they cannot return to the conflict zones but have no safe and legal routes such as resettlement to a more sustainable life either. This is why we are seeing so many people embarking on often dangerous irregular routes.

Early detection and triggering of protection procedures is key. The EU’s Fundamental Rights Agency has also pointed to the problem that we do not have a fully functioning guardianship system in Europe, with each country operating a different system. What is very concerning is the cynical approach we see from certain politicians towards child rights in this situation. Some cite the ‘anchor child theory’ whereby children are sent alone with the sole purpose of abusing family reunification laws later. These allegations have never been backed up by any research. The sad reality is that war and conflict has created many orphans, led to families being separated. In addition to this and perhaps more importantly is, irrespective of the circumstances these children are highly vulnerable and have rights which are not being taken seriously enough by certain authorities. We need to treat every child as an individual with rights and have policies and practices that hold up their best interests given their particularly vulnerable situation.

Not something we would officially comment on.

Guillem Pujol Borràs

Júlia Trias Jurado

At the beginning of the 16th century, Nicolò Machiavelli introduced one of the key concepts of modernity that contributed to building the idea that human beings are capable of engaging with their future, in contradiction to the prevailing God-centric notion of the time. According to the Florentine thinker, fortune was accountable for half of the […]

At the beginning of the 16th century, Nicolò Machiavelli introduced one of the key concepts of modernity that contributed to building the idea that human beings are capable of engaging with their future, in contradiction to the prevailing God-centric notion of the time. According to the Florentine thinker, fortune was accountable for half of the actions of nature, whilst virtue was responsible for the other half. The former continued to be a force beyond human will, but virtue referred precisely to unique human skill. Machiavelli explained this through the following example: you cannot predict a storm (fortune), but you can build a dam to prevent the flood (virtue). Let’s say for the sake of the reasoning, that Europe and its member states incarnate the symbolic figure of the Prince, the ruler who has the capacity to take the decision.

The political dysfunctional management in the current so-called refugee crisis challenges Machiavelli’s thought. In 2015, more than 1 million people arrived in Europe by sea and 35,000 by land. In the same year, more than 3,700 died in the Mediterranean trying to reach European shores. So far in 2016, more than 250,000 people have entered Europe by sea and more than 3,000 have been reported dead or missing. Europe is facing one of the biggest political crises in its history: after the relocation plan for a total of 160,000 people failed in that EU Member States didn’t comply with their quotas, the EU externalized its borders with the EU-Turkey agreement, sending people to a country where there is no guarantee for the respect of human rights. Where did virtue go? How should a virtuous Europe react? Why is it relevant to create a new “Heimat” for the people arriving in our countries?

Starting with the latter question: if there is any ontological feature that defines human nature, it is its relational characteristic. We are a relational species: we exist to the degree that we recognize ourselves in others . There is no “Self” without the “Other”. We learn, grow, and develop through mimicking, and we do that by using language, an inherited common knowledge. Avoiding “the Other” implies the negation of a constitutive part of ourselves, thus neglecting our intrinsic relational characteristic. Making Heimat addresses this same idea. In order to create a real Heimat it is not only necessary to provide the material needs such as a house, food and education, but also to generate an integrative narrative in which the newcomer can identify itself in it and feel “at home”. This is why it is important to expand migrants and refugees’ effective choices about their livelihoods. Making Heimat should incorporate mechanisms where the perspectives and intentions of both refugee and migrant communities would take a role, as well as their political context and outlook for solutions. Structuring participatory assessments taking into account age, gender and diversity approaches are essential for achieving a successful integration process.

The idea of creating a space of horizontal cooperation and popular participation within refugee and migrant communities responds to two essential aspects of a process of integration and of the creation of a Heimat: on the one hand, the self-identification of refugees and migrants within the host city and community, and on the other, the opportunity for the Heimat project to adapt to their potential needs and, by reinventing itself, achieve a successful process of integration. In this regard, the articulation of monitoring mechanisms with a space for migrants and refugees is important since they would allow both popular participation and their input as policy recipients. While ‘Heimat’ refers not only to the inhabited physical space, but also to a place with emotional ties of belonging, it is essential that the beneficiaries can make their voice heard as one more actor of the project, within municipal authorities, civil society groups, and so on. These kinds of participatory programmes would help to have a more comprehensive understanding on the impact of policy and the changes that may developed, and, more importantly, they would be directed at the identification of the newcomers with their daily environment.

Yet building Heimat should not discriminate among individuals. Participatory programmes should also be open to local urban residents with similar needs in order to bring into line local standards and newcomers’ heterogeneous objectives. While in some cases useful, separating the mechanisms performing a ‘Heimat’ for newcomers such as migrants and refugees on the one hand, and on the other for local communities, does not conform with the same idea of ‘Heimat’ since it may not construct a sense of belonging to the broader local community. More importantly, while institutional actors have an important role in this, they are the same migrants, refugees or local communities that need to be identified with a ‘home’. And so, the articulation of participatory mechanisms is essential for a successful process of integration. Indeed, whilst the challenge ahead should be to conceive how to set up institutional and social mechanisms in order to create a new or second ‘Heimat’ for migrants and refugees, it should also not be forgotten that this is to be directed towards the totality of the community. A virtuous Prince would understand that societies are formed by something else than merely the sum of all their individual members: namely, that there is a human need to symbolically identify with a safe place called home.

Pablo Garrido Arnaiz

Guillem Pujol Borràs

Júlia Trias Jurado

What experience can you draw from your former or current professional positions with regards to EU urban development projects directed towards the integration of migrants and refugees? According to my experience, local authorities are key actors for migration management. All over Spain, migrants have access to city registers, irrespective of their status. That’s been […]

According to my experience, local authorities are key actors for migration management. All over Spain, migrants have access to city registers, irrespective of their status. That’s been of the utmost importance in recent Spanish migration history, when millions have arrived in a short period of time. Migrants immediately become city dwellers, and the city is their first space for interaction both with administration and neighbours. The quality of public spaces and public services are key points for newcomers’ integration, as it is for the rest of the city’s inhabitants. Inclusive cities keep public spaces open for all and promote citizen and neighbour interaction. I would see urban development as a powerful tool for that to be done.

Cities need the capacity (which includes financial resources but not exclusively) to strategically plan their responses to mobility-caused urban development challenges, such as the provision of public services and proactive accommodation programs for all. However, local authorities are too often neglected by national (and EU) migration governance, which is focused on border issues. Governing migration effectively to address the challenges of mobility and diversity requires getting cities on board.

This is a tricky question. In many cases, refugees have been forced to leave their own ‘Heimat’. They’re now just looking for shelter, understanding their own feelings and shaping a new life will take time for them. We all guess they want to stay and they wish to stay, but data shows that a majority of them have it in mind to go back to their cities. It will take time for them to work it out.

Having said that, welcoming programs are needed. Housing, child education and healthcare are services that need to be provided on their arrival, while employment is a key point for their social integration. Over these obvious and basic human needs there’s also the need to feel safe and to feel at home, as you suggest. A proactive public policy is needed for that to be achieved. An intercultural strategy can be promoted both by local authorities and civil society for newcomers to be part of the community. Avoiding isolation and promoting participation and interrelation between newcomers and the host society is important for social cohesion. An example of this can be found in the anti-rumors strategy tested in Barcelona and now being developed in other cities. The strategy is making a difference for both newcomers and residents in being an active part of the integration process.

Cities can take advantage of migration, as they’ve been doing so for centuries. Migration has always been the driving force for cities to grow. The journey from rural areas to cities was first happening at national level and today it is an international phenomenon. Jobs are not there waiting for newcomers, as they never have been; local communities have to take advantages of increasing populations to create new economic activity, for the mutual benefit of newcomers and all the local community. Local authorities can promote it. Increasing diversity should be an asset for the city’s position in the global economy of people constantly coming and going.

Migration is the oldest human strategy to improve own life conditions and to give the best expectations to descendents. Globalisation is fueling it, people mobility is an increasing phenomena in the global world. Like it or not, it’s there. We can manage migration or just let it happen. Managing migration is not only about border control. Managing migration means legal channels for entry and accommodation, and that’s very important for hosting countries. It is about labor market and social policies, cities and housing, education, economic policies and economic strategy in the global market. The paradox of anti-migrants is that they do not prevent migration from happening, they worsen the conditions in which migration processes take place and they increase social tension related to it. Managing migration in a multilevel strategy which goes from local to international level is a more sensible option as long as it benefits host countries and countries of origin as well.

This so-called Common Asylum System does not establish a European framework for refugee protection, but instead represents an internal agreement concerning which country should examine an asylum application and under which criteria, and how it should ensure protection is offered in its territory when the application is approved. In other words, the European response to the international obligation of protection and asylum is rerouted to the national sphere and limited to a single default country. Without violating the division of powers, it is possible to go much further in the construction of the common asylum policy provided for in Title V of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which governs the Area of Freedom, Justice and Security. Moving towards ‘more Europe’ means breaking past taboos and daring to establish a real and commonly governed European asylum system. This system could detach the review process for asylum applications (conducted according to pre-agreed criteria and procedures) from effective access to one or other (sub)systems of national protection. The question of where this right of protection would become effective could be determined later, and the joint responsibility of the different member states should be added to the list of determining criteria, and taking into consideration the cities and local authorities, which have a key role in welcoming and accommodating refugees. Such a system could eliminate incentives for non-compliance in countries and encourage newcomers to immediately apply, allowing better management of flows and avoiding secondary movements which engender serious repercussions for both newcomers, particularly the most vulnerable, and the larger society.

Perception is very important on migration issues, as it is on every single issue likely to be extremely divisive, in terms of ‘them and us’. It is very easy to amalgamate in a toxic narrative elements like migration, religion, and terrorism, whether the connections are proven or not, and even if causal relations cannot be established. Nonetheless, populist and xenophobic movements make the case for this relation in a very effective way and with a very dangerous outcome: they create new problems and do not solve the ones they pretend they are addressing. Internal and external security policies need to be developed at EU and international level to protect all of us. We do not have room here to develop this point. Just let me add that besides security policies, social action is needed to engage citizens, including newcomers in isolating terrorists, and terrorism as an option, especially among young people. Pretending they’re all potential terrorists and representing them as such is precisely the wrong approach.

From a legal perspective, there are two main regimes, economic migration for which states have discretionary power, and asylum, which falls into the sphere of rights protected by international legislation. I’m well aware that there’s a thin line dividing both categories, but I do think we must keep a privileged regime for those in need of urgent and effective protection under the Geneva convention. That does not mean keeping migration on the dark side. As I said, we must manage migration.

The so-called ‘illegal migrants’ are not a category at all, but we should discuss and cope with the fact that a number of asylum seekers and migrants will fall out of both categories. When repatriation is not an option we should find a way out. Protracted situations of legal limbo are dangerous for migrants in such situations and for hosting societies. Cities are especially concerned by this, as they have neighbours not recognized by the State but effectively living there.

I do think migrants should be seen in a city just as residents and neighbours are. The more the city and its urban public space promote inclusiveness and cohesion for all, the more it will ease integration processes. Over the very short term welcoming strategies to remove barriers and obstacles, all residents should be included in local services planning. In that sense, I do not think multiculturalism is a good strategy for local integration strategies, understanding it as a set of ‘communities targeted’ public policies. The existence of high quality services and inclusive public spaces for all is the relevant question. Indeed, a proactive policy is needed to accompany newcomers on their way to effectively becoming city dwellers, that meaning public policies aimed to remove barriers for them to get access to services and to public spaces, making intercultural relations possible.

Irena Guidikova

What the great imperial, commercial and intellectual centres of the world have had in common throughout history is the diversity of people they attract, and a talent for stimulating and managing cross-cultural exchanges. They success is to a large extent due to what Charles Landry and Phil Wood have called the diversity advantage (the diversity […]

What the great imperial, commercial and intellectual centres of the world have had in common throughout history is the diversity of people they attract, and a talent for stimulating and managing cross-cultural exchanges. They success is to a large extent due to what Charles Landry and Phil Wood have called the diversity advantage (the diversity concept Landry, C. and P. Wood: 2008).

For centuries, human mobility and the resulting diversity of languages, religions, lifestyles, ideas and skills have been drivers of knowledge generation, growth and productivity in destination cities. For the most part, these benefits have been the result of organic processes of inter-cultural mixing and interaction in the context of daily life. However, they have usually come at a significant human cost. Creativity and innovation have often been driven by friction and conflict between ethnic and religious communities, the expression of both a survival instinct and the will to succeed despite formal and informal barriers and exclusion mechanisms between culturally defined communities. Until a few decades ago, community cohesion was not an aspiration or even as a possibility, neither was dealing with cultural diversity seen as a task for public authorities.

Today governance, in particular at the local level, is (in principle) more informed, ethically enlightened and resourced than ever before: nations and cities can use benign social engineering in order to reap the benefits of diversity while minimising its costs. But nations and cities are not equal vis-à-vis the demands of diversity management. While weakened nation-states tend to fall prey to populist leaders conjuring the cultural homogeneity of an imaginary golden age to mobilise voters’ fear of change, cities embrace diversity as a motor of development. In urban centres, the laisser faire of old is increasingly replaced by urban diversity strategies in an attempt to counter the natural processes of segmentation and segregation that foster inter-group mistrust and animosity and accentuate socio-economic divides.

Even in countries with a strong multicultural tradition, a strong awareness is emerging of the need address ethnic segregation – both special and mental – and focus urban policies in creating mixed public spaces and inclusive institutions competent in managing intercultural relations in a proactive, positive way. Such awareness is welcome as in the multiculturalism’s own showcase countries Ideological and social divides run deeper than ever. More and more people lead segregated lives, only meeting and communicating with those who think like them. Pluralist, open-minded public space is shrinking.

Urban diversity and inclusion strategies are growing increasingly sophisticated and intercultural (it no longer makes much sense to speak about majority and minorities in cities like Geneva, London and Amsterdam), less reliant on massive regeneration projects and iconic landmarks designed to attract strangers, not build communities, and more on fine-grain “eco-systemic” approaches involving inhabitants as architects and masterminds of their own place-making. The humbling of urban planners has coincided with the rise of community developers skilled in creating substantive dynamics connecting people around designing shared spaces which can foster a pluralist urban (neighborhood) identity and a sense of belonging. Some of these dynamics are so profound and sustainable that they effectively convert into lasting mechanisms taking cities into the dimension of participatory democracy.

We are just in the beginning to building a nuanced understanding of how such open-minded spaces emerge and the importance they hold for the local community. Publicly owned, flexibly defined in their function, sometimes managed by the users, these are spaces where unexpected and unplanned things can happen – from a flash mob to a pup-up civic agora, guerilla gardening: spaces where risks can be taken, where people can engage in doing things together rather than just talking, going over the barriers of language skills and low self-confidence.

Cities like Reggio Emilia in Italy and the London borough of Lewisham, when engaging in bottom-up neighborhood regeneration of “problematic” or unsafe areas (in many cases in the aftermath of traumatic events such as urban violence or racist murders), have found that in order to ensure a democratic and inclusive process, it has been necessary to go door-to-door with interpreters, so that people of different backgrounds and levels of mastering the local language, could contribute to the consultation process and voice their concerns without having to take part in formal meetings. Making the effort (and the expense) of involving everyone in a more than formal community consultation not only sends a signal to residents that everyone matters, but also helps shape a project which resembles the local community in more than one way.

Some cities are even considering imposing a special “tax” on developers for an artist-led community engagement process throughout the entire urban regeneration process, instead of, as usual, involving artists as an afterthought, for superficial “embellishments”.

Artists-led regeneration is a way of giving the city back to the citizens but also bringing the cities to the spotlight. Loures and Nuremberg involved famous graffiti artists in creating the mural paintings based on the stories and narratives of the inhabitants in the districts of Quinta de Mocho (Loures) and Langwasser (Nuremberg) in an attempt to change the image of these diverse and rather deprived neighbourhoods and give them a new impetus using diversity as a source of inspiration. These initiatives have successfully managed to change external (feeling of insecurity, fear of migrants) and internal (lack of self-esteem, lack of ownership) prejudice around the neighbourhoods. Such developments are inherently intercultural as they harness the creative power of diversity by intent, seeking to dig out and blend unique cultural perspectives and personal stores into a potent narrative of a pluralistic place which is happy to accommodate many different identities and be constantly redefined by its changing demographic realities.