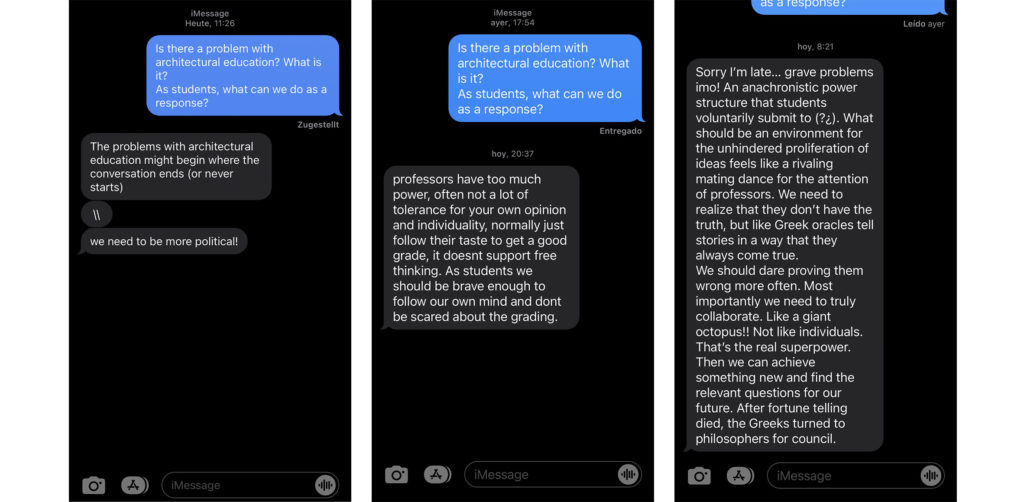

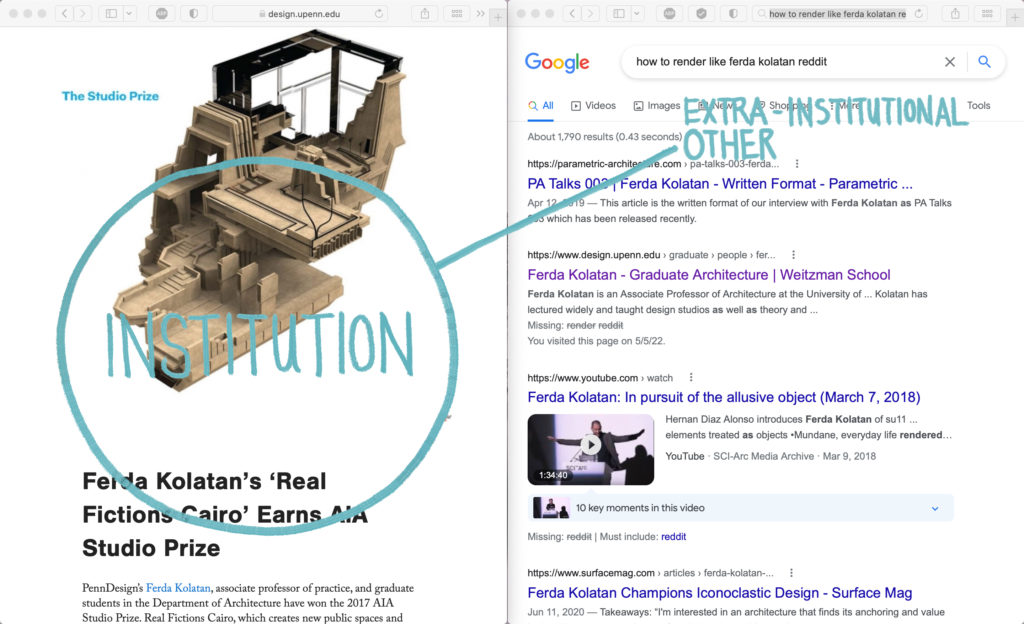

In a practice whose information is as inaccessible as that of architecture, it is a relative shock to witness the recent proliferation of external resources that pursue the exact opposite effect. This has led institutions to pose the reasonable but fatalistic question: “What is the purpose of the institution and the diploma in the face of this rising tide of change?” What they fail to realize is that extra-institutional, spontaneous acts of learning have always and will always continue to exist, occurring constantly for learners of architecture. It is only that technology has increased the urgency of these acts, while making it easier to meet their needs.

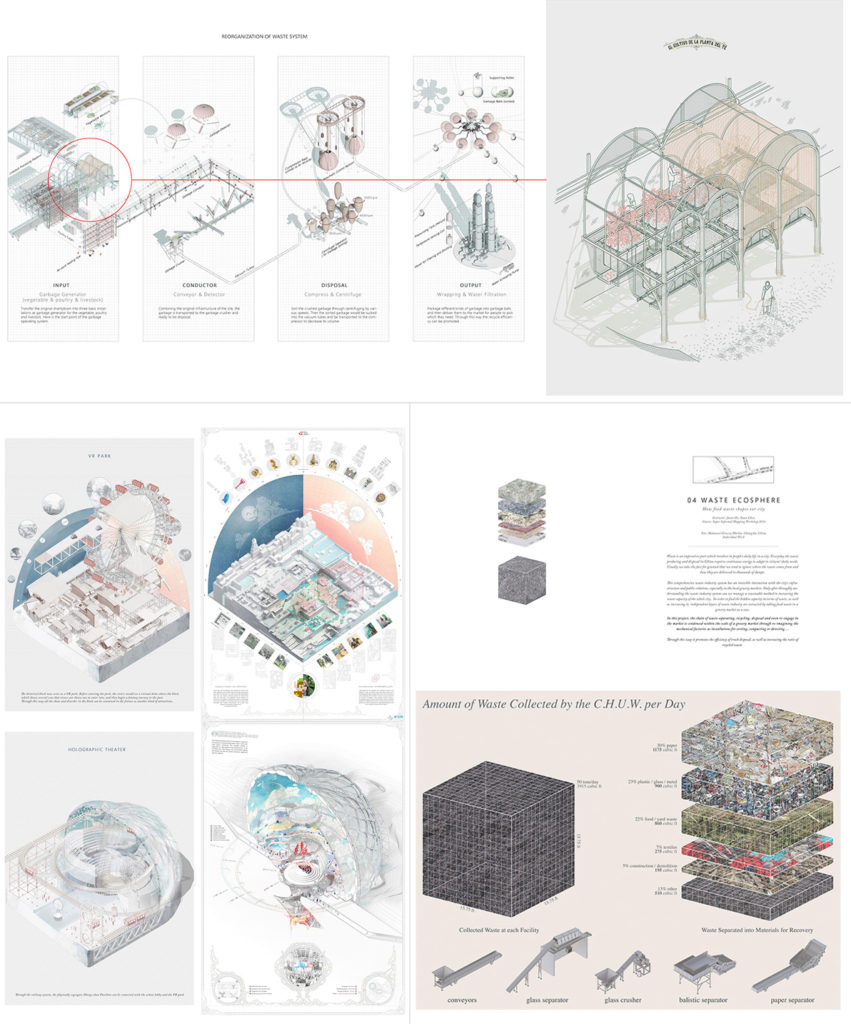

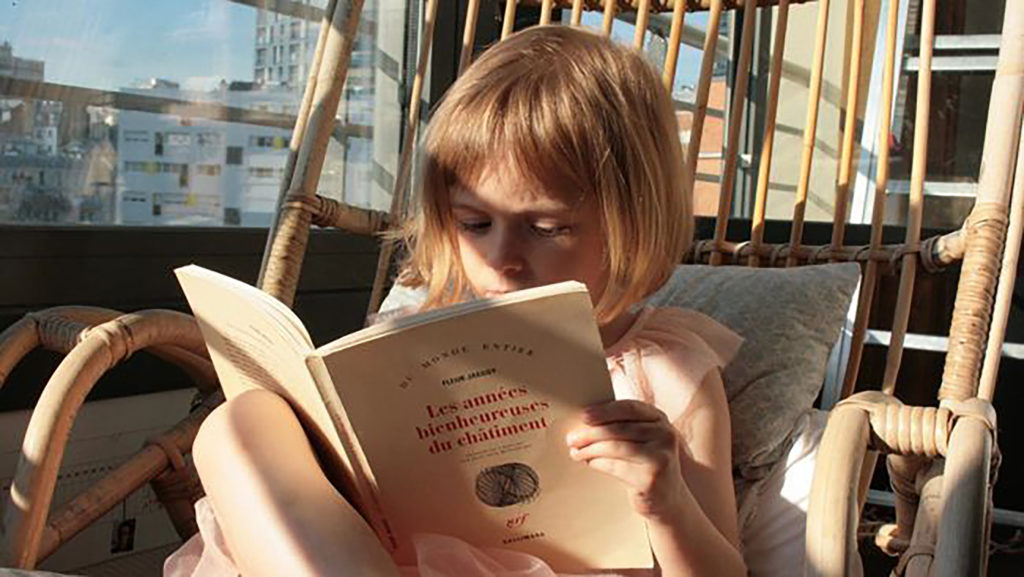

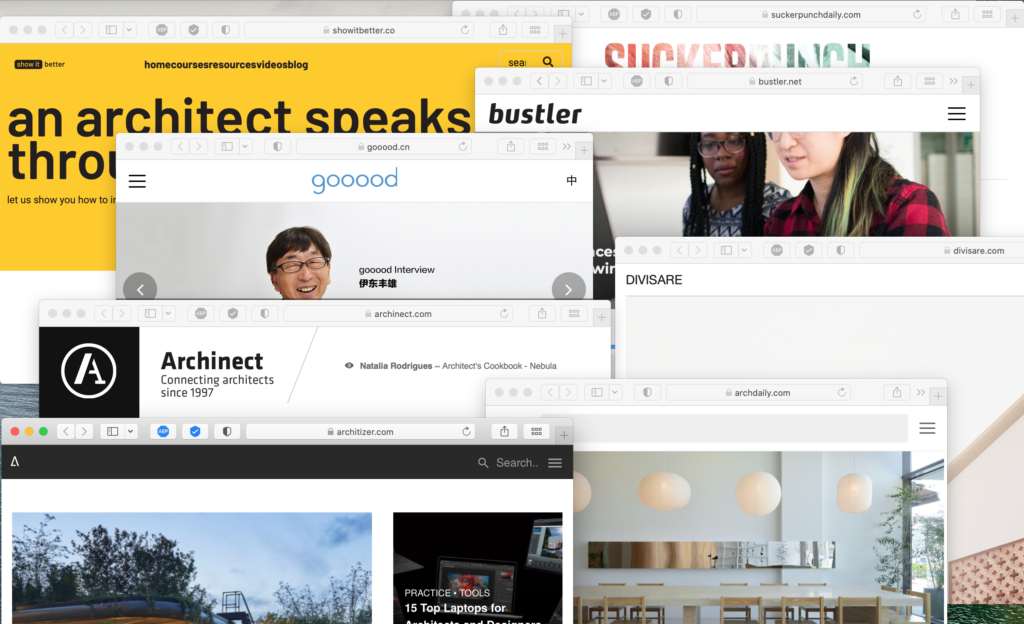

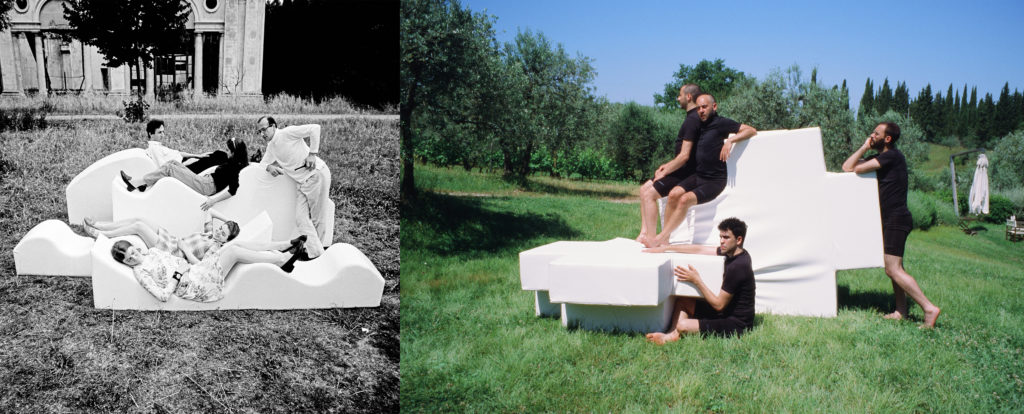

Today a seemingly limitless number of extra-institutional resources exist – from Archdaily for images of built work, to Detail Magazine for construction detail drawings, SuckerPunch for experimental student work, and Instagram for a variety of architectural content. This only scratches the surface of the new world of content; there are also those that aggregate job listings, open calls, and design requests, and those that, like Show It Better, provide educational material for aspiring designers to learn better representational strategies and ways of approaching matters of mental health. Given this condition, immediately two questions arise: one, what sort of pedagogical circumstances does this create for the learner? And two, with this surfeit of content, is this not enough to render the diploma obsolete?

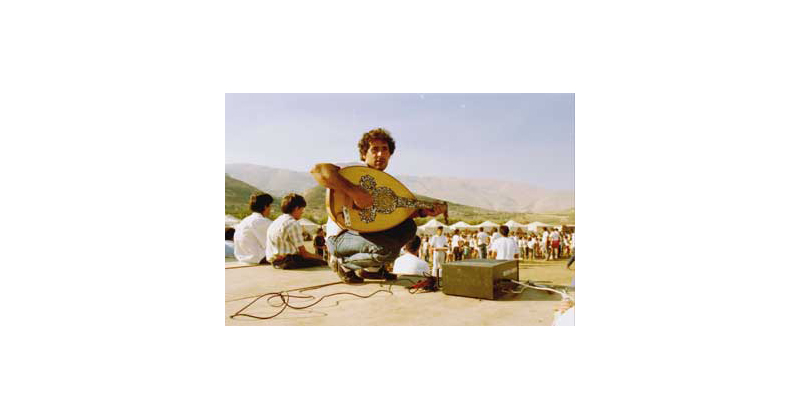

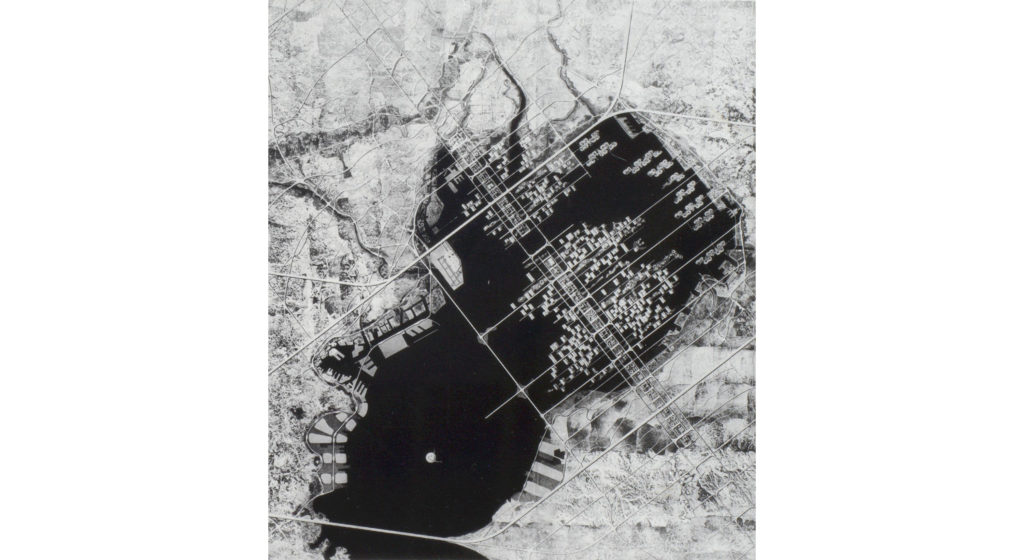

From Gooood to Archdaily, the number of extra-institutional resources available to today’s students and professionals is essentially infinite.

To the first question, we can see that at the moment, studying within the institution often requires the student to search feverishly through YouTube videos, Reddit posts, and the like for tutorials, examples, and information on how to obtain a desired effect in software, how to produce a type of drawing, how to generate clean 3D prints, and so on. In other words, studying within the institution at present often leads the student to search for information outside of the institution. However, this is not a new condition. The generation before them also looked outside – digging feverishly through copies of Detail Magazine for examples of wall sections, copies of articles with tips on model making, and so on. The generations before them as well – whether through monographs and pamphlets, magazines and photocopies, or forum posts and video tutorials, despite how present conditions appear, the compulsion to look beyond the institution for requisite information is ubiquitous and inherent.

This is because the search itself is timeless – there is always a desire to find inspiration, relate to a zeitgeist, and consume examples of contemporary architecture outside of the paywall of the monograph, museum, architectural association, or university. What has changed in our time is the number of resources, multiplied as a consequence of technology’s capability of both meeting and heightening that desire. As such, this intrinsic pull to learn is exacerbated evermore; the plethora of extra-institutional material only serves to make it more frantic. Desire is insatiable and, in psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s words, metonymic; even with a seemingly limitless supply of free information and inspiration, it remains unsatisfied. In this way it persists ineradicably, occurring regardless of the pedagogical context.

Not only is this the nature of desire vis-a-vis learning, but it is also the very nature of the practice of design. Design itself is frenetic and is, in some ways, a long list of problems to solve – problems for which it is impossible to completely prepare in advance. There is always that which is not-yet-learned, and there are always problems that require one to know that which is not-yet-learned. As such, the act of design, like and as learning, is always incomplete, always spontaneous, and always in some way urgent. It is a search at times for outlying information and at other times for an outlying desired outcome. This is design, and, synchronous with the act of learning itself, it is what stimulates extra-institutional learning.1

Of course, though the desire for extra-institutional material is timeless, this condition still points to a lack in institutional pedagogy itself – there is indeed that which institution is failing to fulfill. However, this lack is not discrediting to the institution – rather, it is immanent. Much like design, education, architecture, and life itself are continuous and unpredictable, and this remains the case whether academia is standardized or lightweight and motile. As such, the necessity for independent forms of learning and teaching will always exist. It is not up to the institution to try to encompass all existing and possible forms of knowledge, nor would it be possible; the organization and hierarchy of the institution make it too slow relative to the development of technology, the needs of each student too particular, and the time and budget provided likely far too small to accommodate every course, tutorial, or instruction that might be useful to the architecture student.

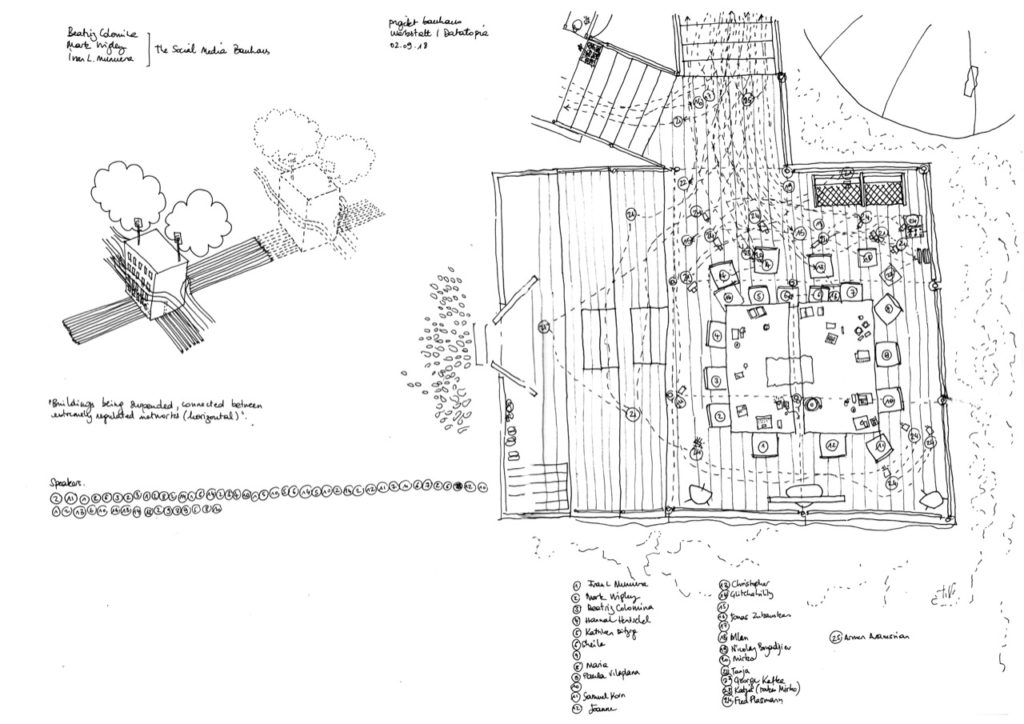

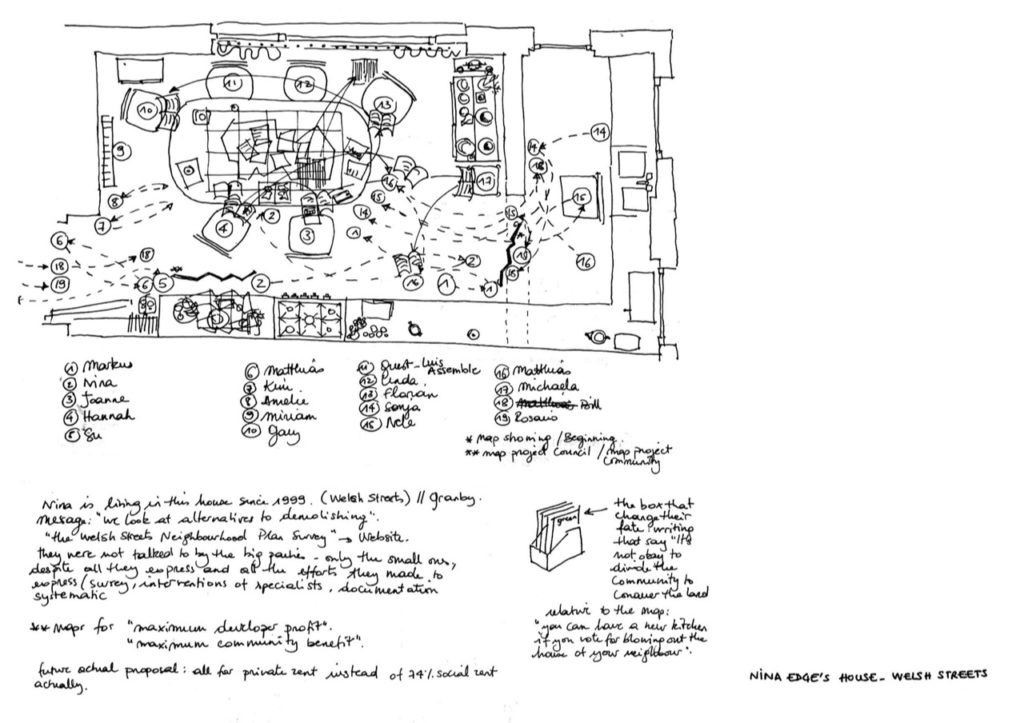

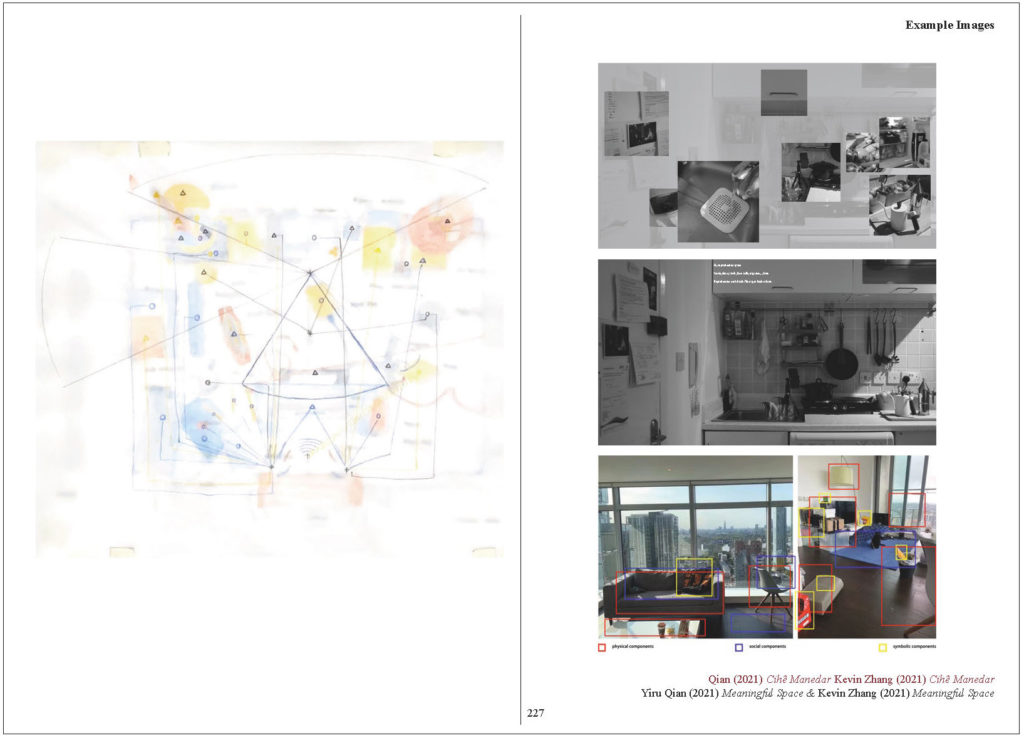

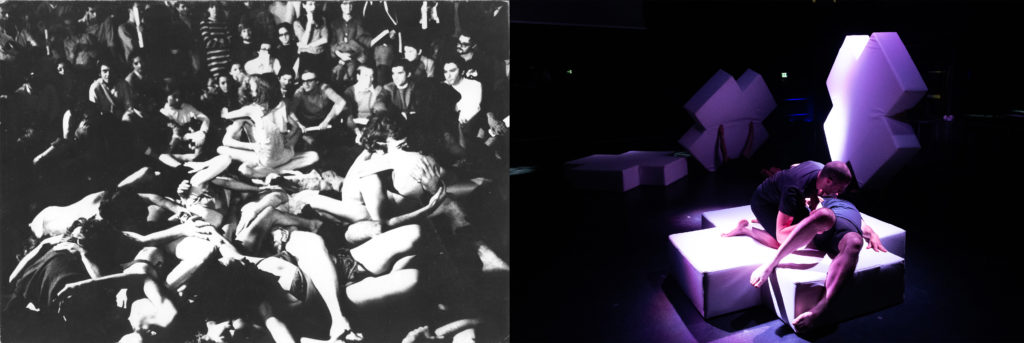

Diagram of the institution as enclosed and given identity by its other. Without the extra-institutional

– in this case, everything not part of the institution

– the institution would fail to exist as a defined entity.

Were that to be the case, this diagram would depict an open circle without a name.

To respond to the second question2, this lack does not invalidate the diploma – in fact, it is precisely what sustains it. Independent forms of learning are the outlier, the other that upholds and delineates the whole; they are what allow the institution to exist. As black makes white, and that which is alien delineates that which is familiar, that which is not institutional is exactly what gives meaning to the institution. Speaking simply, difference produces meaning. Speaking in terms of set theory, the establishment of a set requires an other, external term to provide a name and outline. Speaking practically, this idea is demonstrated in three ways. One, extra-institutional artifacts generally give rise to institutions themselves. Some of the most famous published works in architectural history were extra-institutional, and often it was because they were extra-institutional that they were famous, and because theywere famous – i.e. popular – that they were extra-institutional – i.e. popularly distributed. These works generated ideas around which schools of thought formed; later, these schools of thought either developed into new institutions or were integrated into existing ones. Institutionality is ex post facto; existence is predicated upon a clarity of concept and purpose, and death and rebirth are predicated upon a loss of lucidity and an acquisition of new clarity, respectively.

Take Vitruvius’ De architectura – both the first work of architectural theory and the first extra-institutional work of architectural theory in the Western canon. Produced roughly between 30 and 15 B.C., De architectura covers a wide range of architectural considerations, from the identity of the architect, to ideal aesthetic principles, to lessons on building technology. Only some fourteen to fifteen-hundred years later did it reach cultural prominence, appropriated by Renaissance humanists who found in it not only guidelines for building methods and designing with proportion but also the very definition of architecture itself. This document legitimized, structuralised, and affirmed the notion of architecture as a distinct practice; as such, Renaissance architecture as a school of thought flourished, and the first institutions in this tradition gradually emerged. For instance, in Renaissance humanist and Vitruvius acolyte Leon Battista Alberti’s De re aedificatoria, De architectura found a successor – the first architectural treatise of the Italian Renaissance – and in Alberti himself, the extra-institutional treatise found itself heavily influencing one of the most powerful institutions of the time – the Vatican, for whom Alberti was architectural advisor. In another instance, Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio, following Vitruvius’ treatise, wrote his own – I quattro libri dell’architettura, a document so influential it established a school of thought (Palladian architecture) that would continue to be sourced for centuries to come in municipal and educational buildings from Prussia to the British colonies.

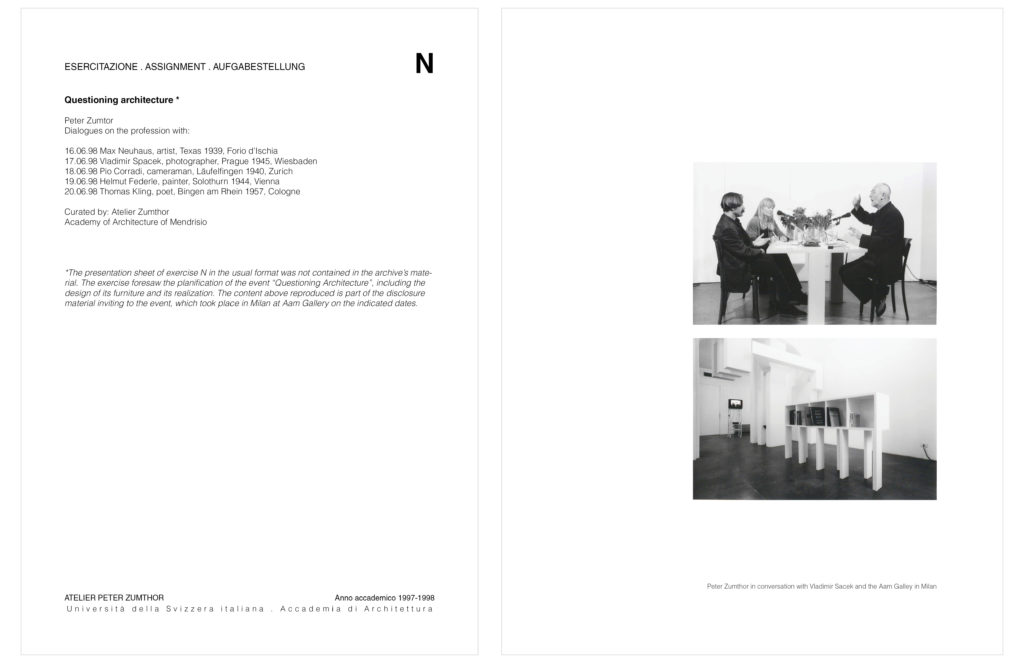

Le Corbusier is another prominent example of the extra-institutional intrinsic effect on institutions. The Swiss-Frenchman received no formal architectural training; he was more or less self-taught. Coming from a background in painting and watchmaking, Le Corbusier, through extra-institutional enterprises in the founding of magazine L’Esprit Nouveau with Amédée Ozenfant and Paul Dermée, the writing of his seminal manifesto Vers une architecture, and his many residential and urban-planning designs, has inexorably defined how one thinks about and learns architecture within the institution. He is one of the critical standard-bearers of Modernism, his identity as a polymath who dabbles in furniture design, writing, and urban planning defines the image of the ideal “architect,” and his multimedia approach, mirrored by his Bauhaus contemporaries and reaffirmed today by architects like Steven Holl, still defines the architectural curriculum in most American universities today. Like many of his contemporaries, he came from an extra-institutional background, but the establishment of the CIAM, the inclusion of his ideas in schools’ curriculums, and the reception of an offer to teach at l’École des Beaux-Arts reveals that both new institutions emerge from and existing institutions adapt to revolutionary outsiders.

Through Vitruvius and Le Corbusier, we can see how extra-institutional ideas both create institutions and cause profound change within existing institutions. Institutions, however, are not passive affects of extra-institutional ideation – nor is there a 1:1 relationship between the two. Institutions are agents interacting with and appropriating external ideas, attaining not only ideas but also excess content; that is, exceptional status and meaning. The revolutionary other, from self-published manifestos to YouTube videos, does not merely establish the institution; it enriches it and thereby creates it as a remarkable entity. What makes the institution and its experience so edifying, enjoyable, and challenging is the inclusion of and confrontation with external resources. Whether it is the provocation of Vers une architecture, the revolutionary air of 1968, or the rise of computer-aided design software, institutions are inevitably faced with do or die moments; it is in how they confront such moments that determines whether they survive and to what extent they remain significant. Why degrees at Delft, Harvard, or SCI-Arc are important and why such universities continue to exist is largely due to how they and their students engage with extra-institutional resources. Consistently forced to face new external opposition, their relevance is predicated on how they choose to incorporate new ideas. The result of this conflict is what gives meaning to the diploma.3

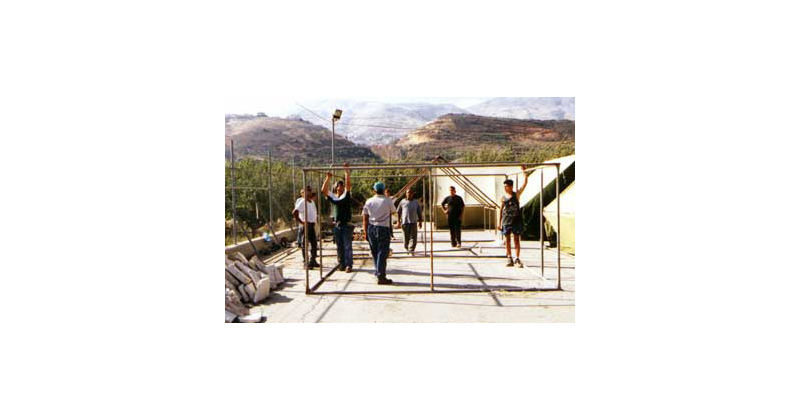

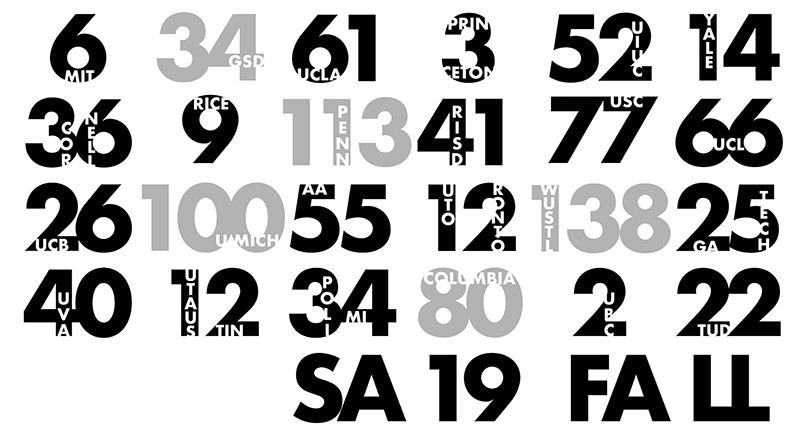

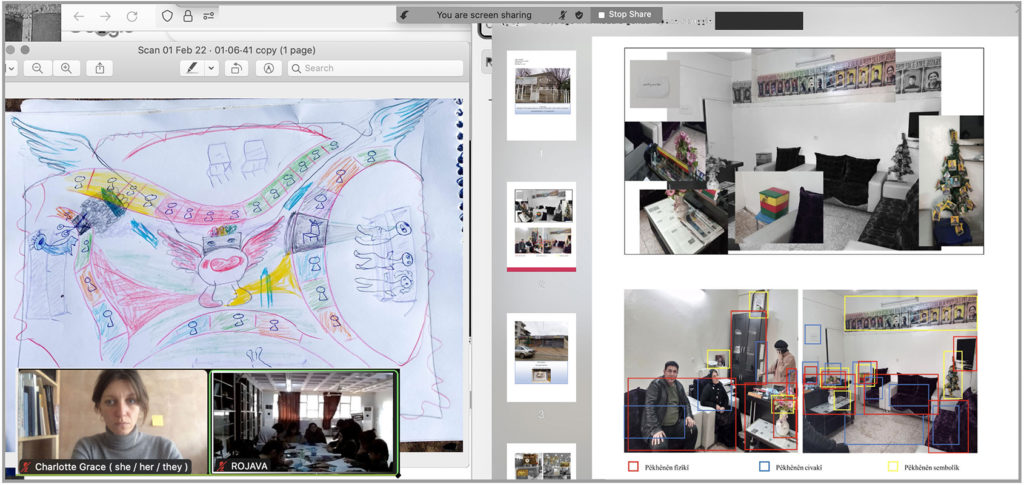

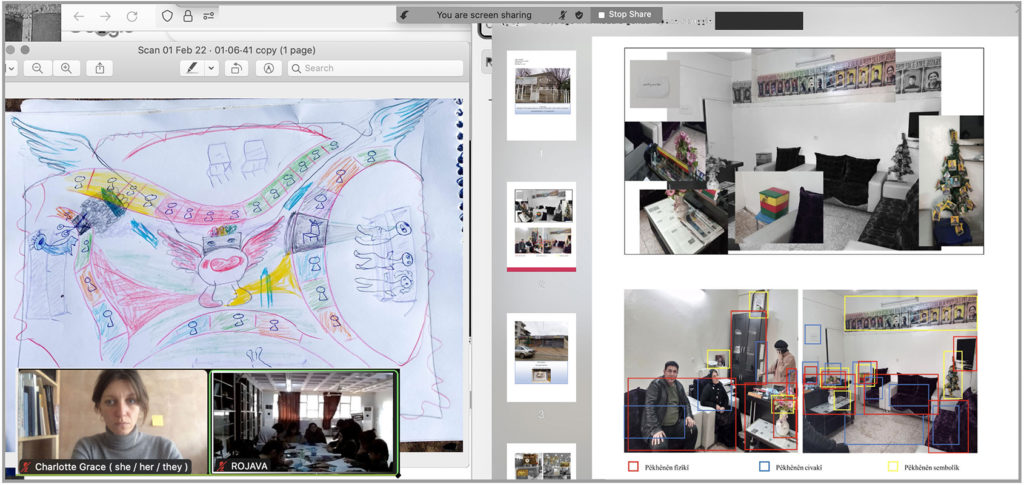

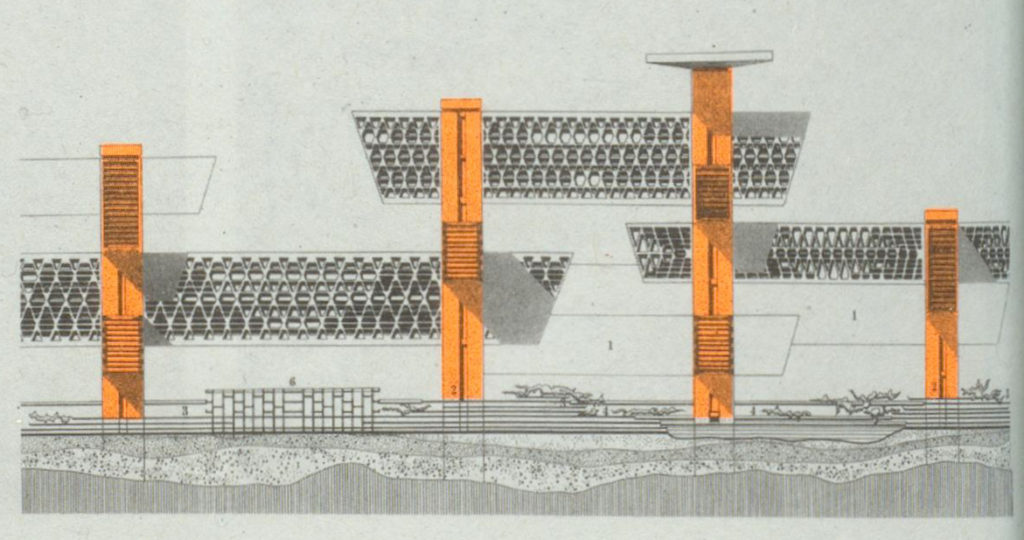

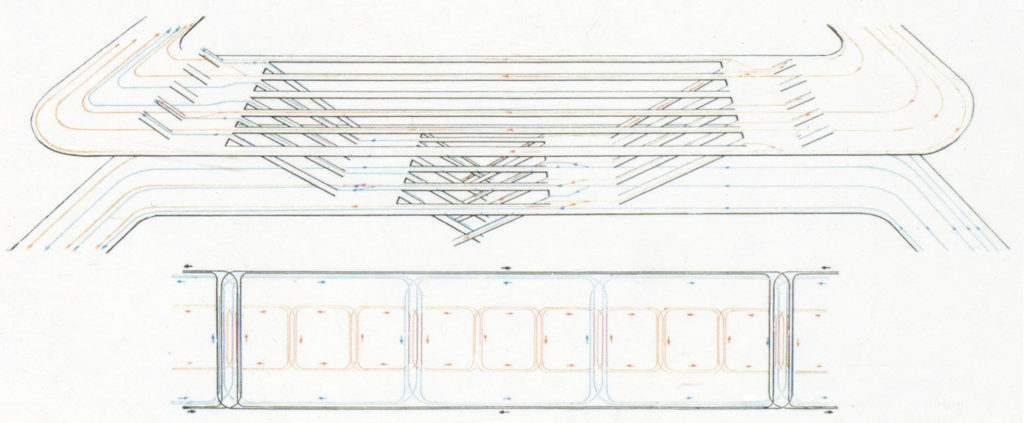

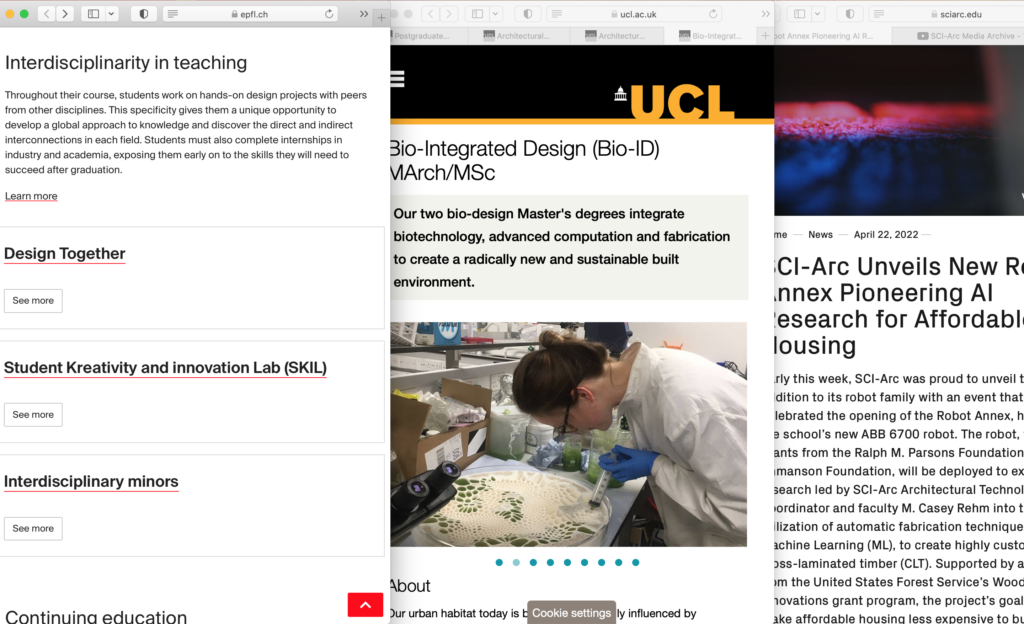

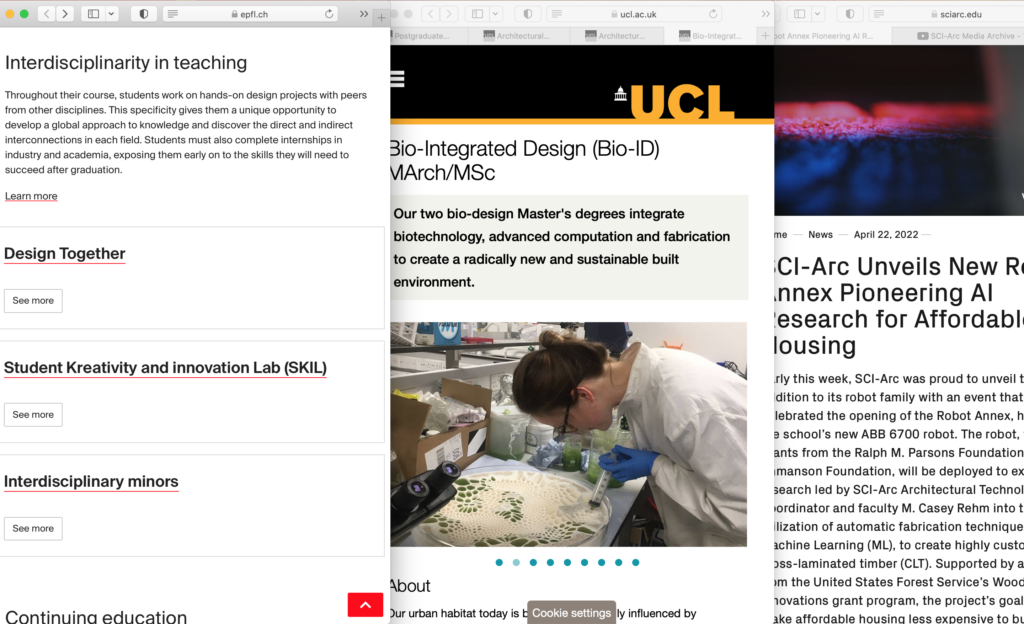

Institutions such as l’École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne, the Bartlett, and the Southern California, Institute of Architecture have attempted a variety of ways to integrate extra-institutional ideas and contemporary trends into their degree programs and facilities.

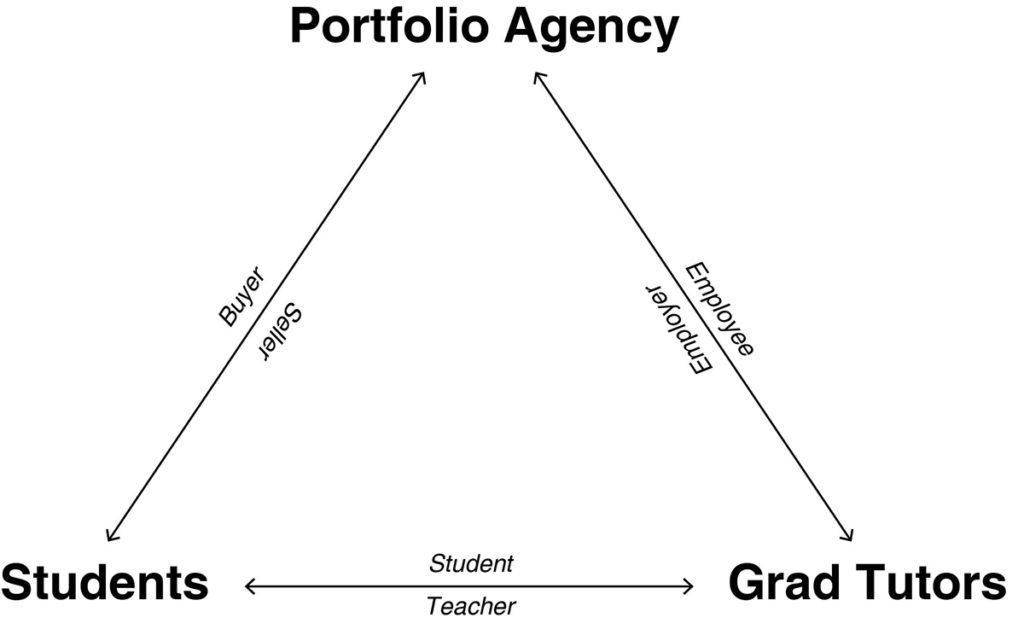

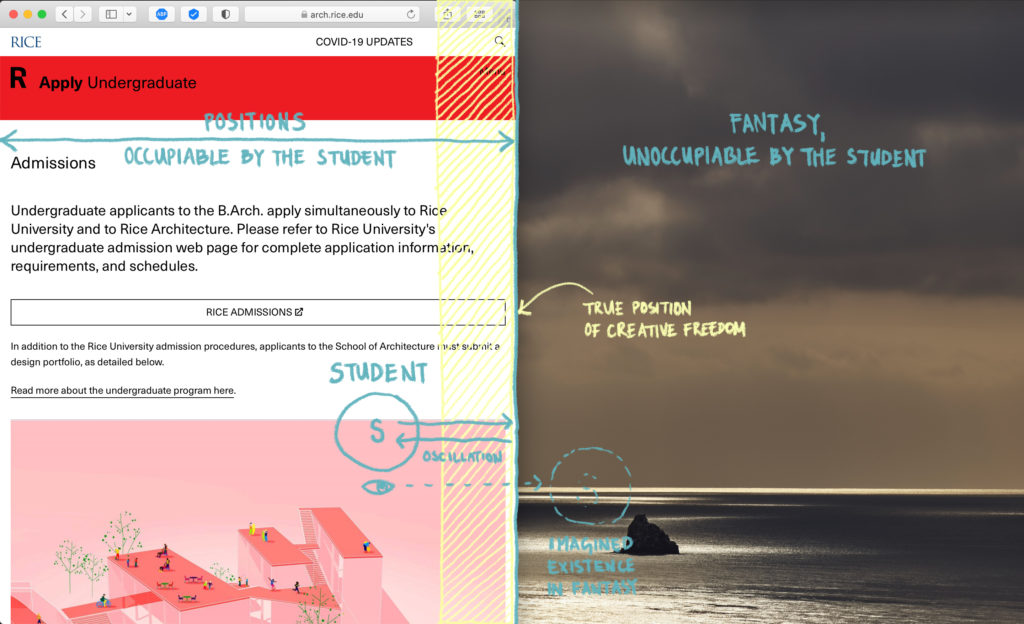

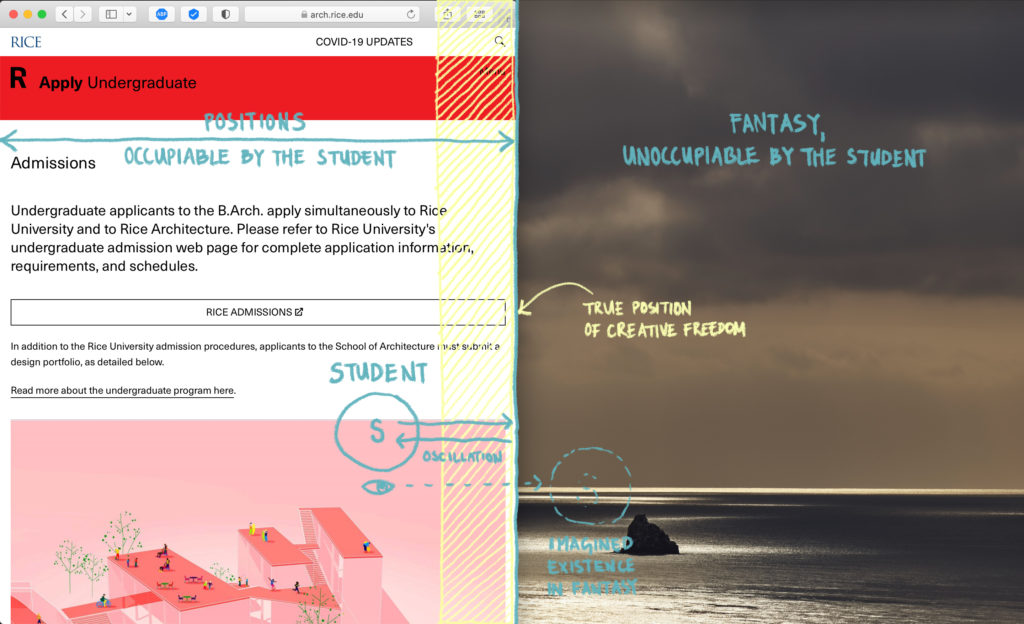

Two, without the exception, what might we consider to be the difference between the institution supporting the diploma and other established structures like an apprenticeship at a workshop or work at a practicing firm? We might say that the empirical difference lies in how the authority figure demands of the learner. To the apprentice, at least in contemporary situations, the master says, this is how to do this, repeat after me. To the employee, the firm demands, do that for which you are paid; you are welcome to offer your own thoughts only if there is time. To the student, the school asks, given a design prompt and some criteria, what can you produce from the depths of your imagination? In the diploma, the student is given a degree of independence and the ability to work on their own solution to a relatively abstract prompt. Perhaps, then, this is how the diploma stands apart; compared to the apprentice or the employee, the student is freer in the pursuit of a personal design project.

Nevertheless, the student remains ensnared within the institution and what the institution considers good, complete, or otherwise qualitatively superior. Inexorably caught between the freedom offered by the institution’s unique conditions, and the institution’s authoritative “no” – its authoritative evaluation of work and particular preferences – what is the student to do? Perhaps the student should renounce the diploma in the pursuit of total freedom, as plenty of ambitious and/or financially incapacitated students in other disciplines have done. In the case of architecture, however, this nexus on the frontier of total freedom, where the student oscillates between enticing glimpses of a glittering Garden of Eden and the steadfast demands of the instructor, is perhaps the truest position of creative freedom. It is only upon encountering the institution that the student begins desiring for a world beyond the institution; to both reverse and reiterate a previous point, it is the institution that creates the extra-institutional fantasy. It is through responding to the imposed demands and imposed structure of the diploma that the student learns to iterate – to repeatedly attempt to produce proposals that aspire to satisfy the figure of authority. It is in doing so that the student learns to demand in response, “che vuoi?” – “what do you want from me?,” “what more can i do?” Through this, the student learns to struggle, and in struggling, learns to think critically about both their own work and the work preferred by the figure of authority. Whether or not they choose to agree with such preferences is a critical consequence of, though not exclusive to, the institutional process.

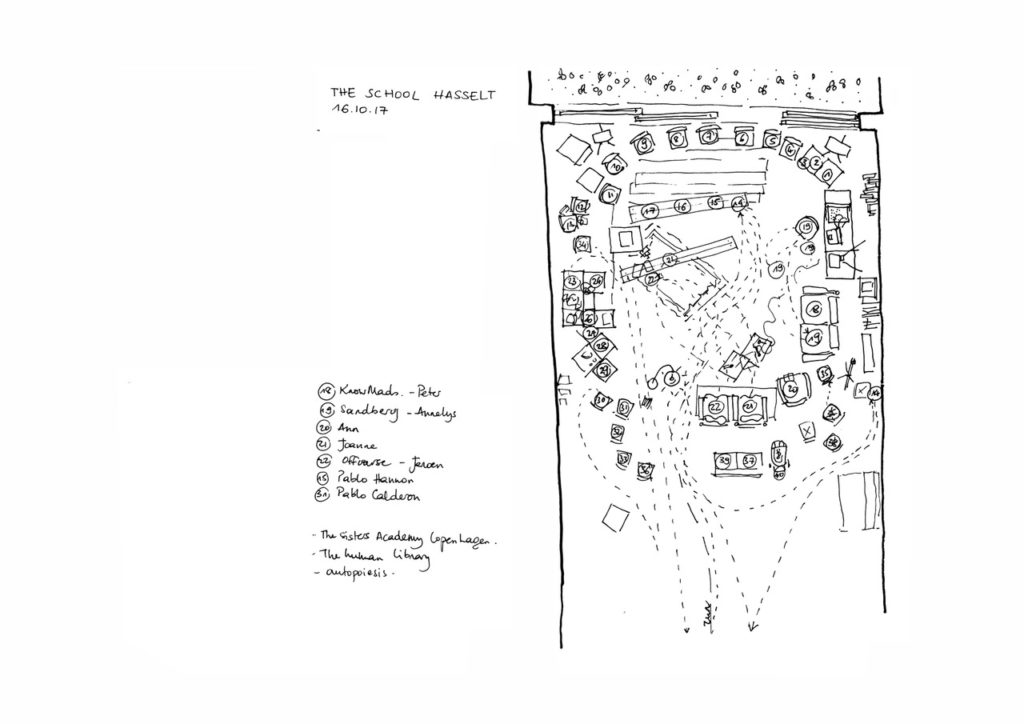

The true position of freedom is on the boundary between the institution and its consequent fantasy of an idyllic other.

Immanuel Kant’s notion of freedom is imperative here: true freedom arises from discipline. The structure imposed by the institution generates the conditions for the acquisition of true freedom; it is in the desperate struggle against and within it that they discover what it is to be creative – that is, to flow, to fly. Through struggle, and as a rejoinder to the instructor’s abstract requests, the student falls upon extra-institutional resources for inspiration, support, precedent, and a competitive advantage – whatever it takes. In struggling to sift among the torrent of material covering the entire qualitative spectrum, the student comes to terms with what they think is good and bad. Thus, the student, through the institution and experience with extra-institutional material, ideally comes to understand their own project and practice – coming to understand what it is to think seriously about architecture. The institution and its other go hand in hand; it is the diploma that makes the enticing world beyond the diploma, and the world beyond the diploma that underlines and bolsters the diploma. Within their gap lies the position to be free, a position that simultaneously conceives of and strengthens both extremes.

The most important figure that the diploma endows is that of struggle, and the most important quality that it incites is that of critical thinking. The niggling question that asks whether a diploma is necessary given the increasing number of readily accessible online learning material implies that the diploma’s value lies in a name attached to a garrisoned quantity of exclusive information. Without such exclusivity, the diploma is reduced to a mere name. This misses the point. A diploma is and remains valuable not for the trust embedded in the name of the institution that administers it; a diploma remains valuable precisely for the struggle that occurs against, within, and beside the institution from which one receives the diploma.

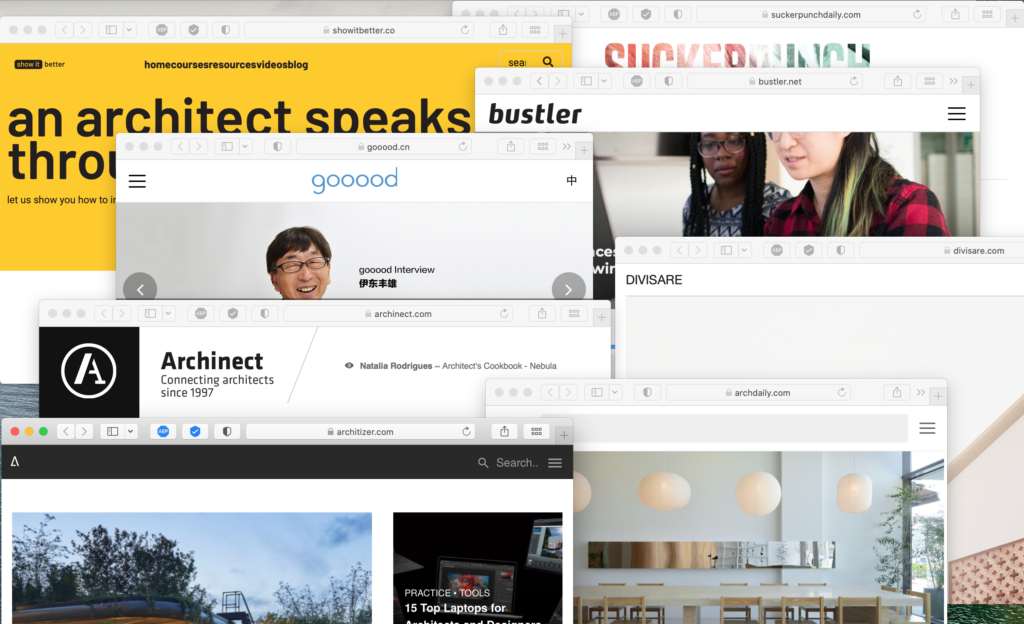

This is the third way in which the extra-institutional other sustains the institutional whole. What is the YouTube tutorial? It is not a group of students crowded around a studio desk in jovial conversation. What is a detail from a magazine? It is not observing an instructor mark up a classmate’s detail. Ostensibly these comparisons are entirely contingent – one could just as easily say a YouTube tutorial is not thousands of dollars per year in tuition or that a studio critique and review is not the extra-institutional ability to decide one’s own hours of learning – but the point remains the same. However sizable the lack is in the diploma, there is an equally sizable lack in the study of external resources. The diploma is as special as its other because of its unique struggle – it is years of work, afternoons spent huddled over a model, pizza parties in studio, rampageous scrawlings in a sketchbook before class, a cry over a project, and a cheer at the end of a semester. It is a fine arts degree, a furniture design degree, a history degree, a philosophy degree, a degree in interpersonal relationships, and a coming of age – it is all of these things. What makes the diploma in this instance is both additive and differential; it is the sum of communal experiences of joy, struggle, and longing – experiences that are conspicuously absent, or at best, desultory, from extra-institutional learning.

This multifaceted experience, this multifaceted struggle, and this struggle against this multifaceted experience is ultimately what produces the architecture student and what prompts them to think critically. As aforementioned, this is what the diploma does by definition, but it must go further – expanding and enhancing this capacity in acknowledgment of contemporary conditions. The struggle of the student against the authoritative Other has always existed, as has the struggle against the qualitative spectrum of the extra-institutional other. The ability to think critically as a point of clarity developed in riposte to the struggle has also always existed. Struggling against the will of the institution and struggling with and against one’s classmates – the degree of this more or less remains the same; however, struggling amidst a deluge of resources and information – the severity of this increases evermore.

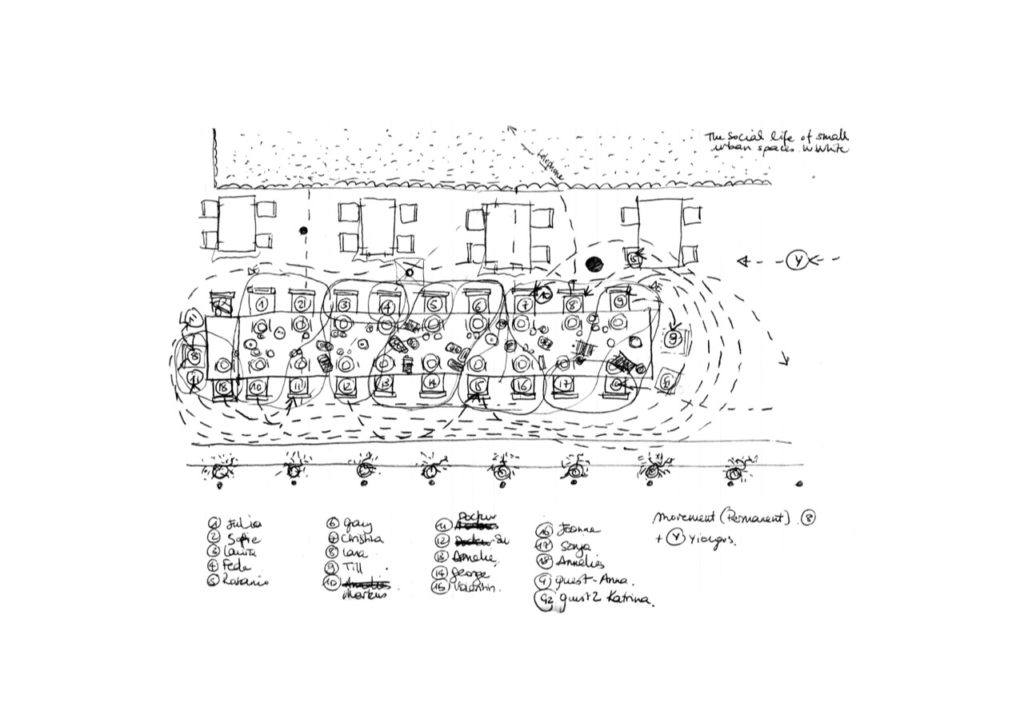

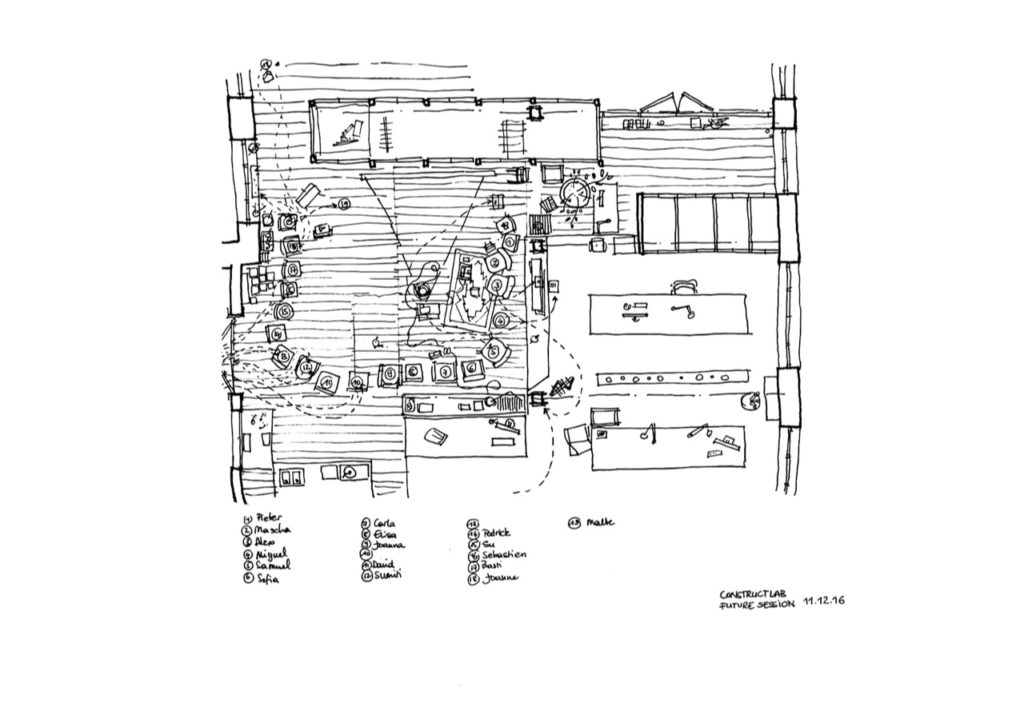

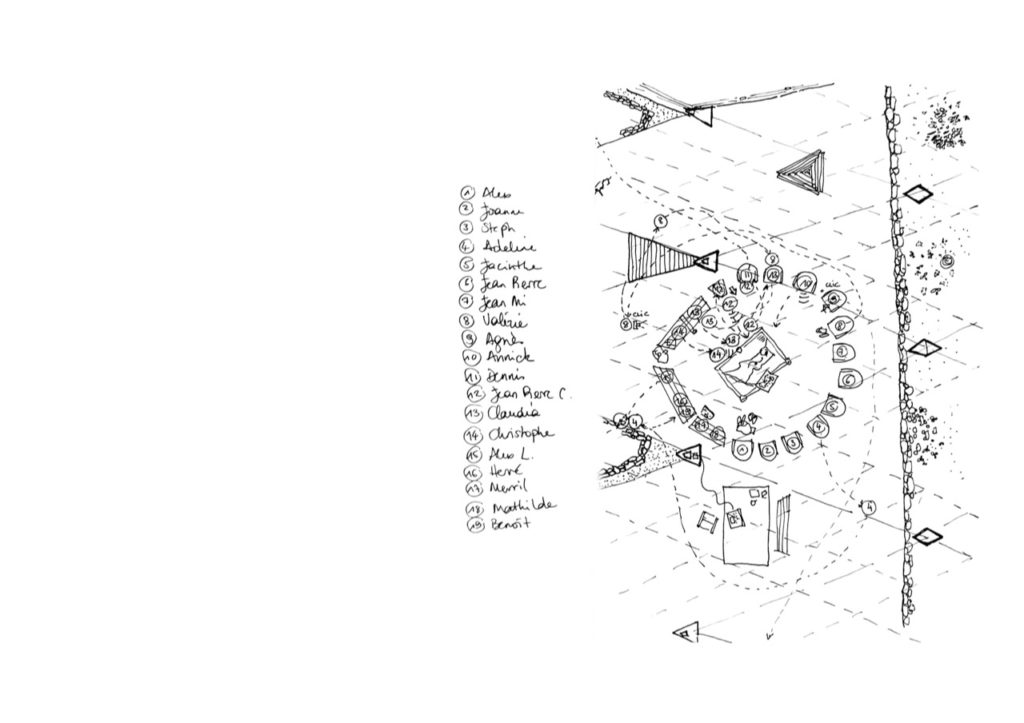

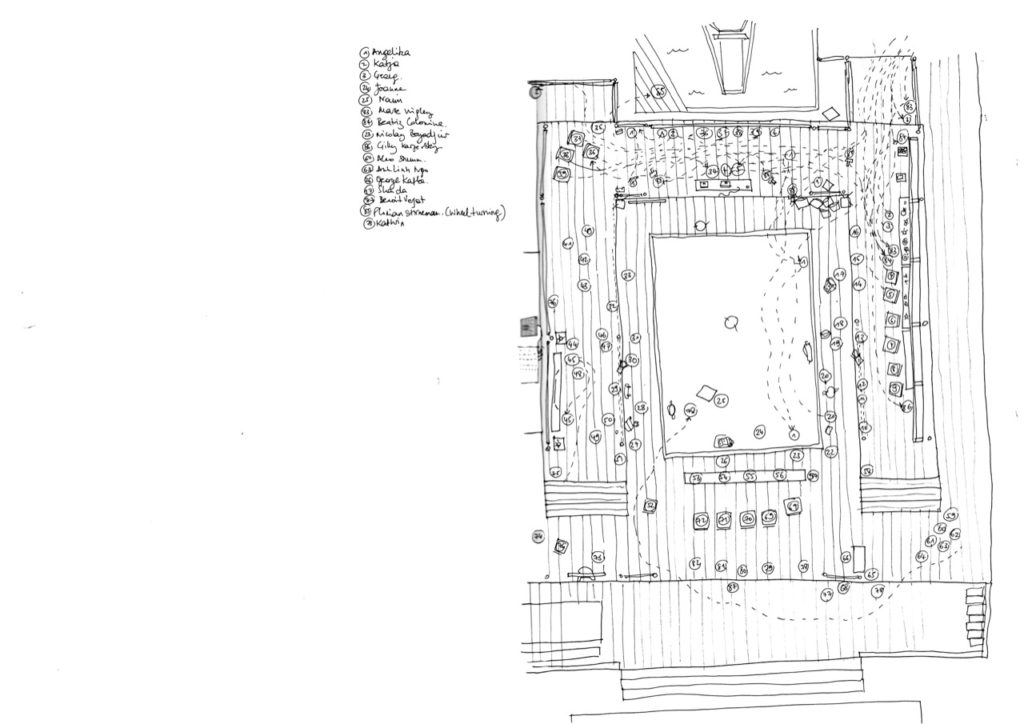

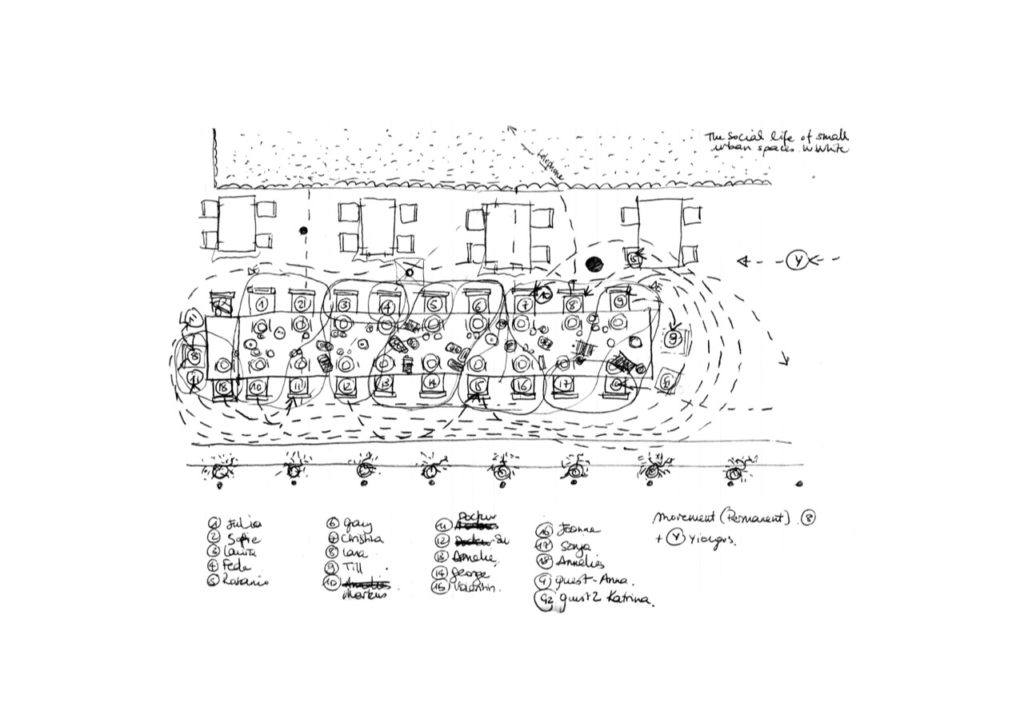

The struggle, joy, and absurdity unique to the diploma experience.

As a consequence, perhaps the university, rather than relying on handfuls of youthful instructors (under whom only a select number of students can study), or following the capricious tides of developing technology and academic and aesthetic trends, should revise its pedagogy to include critical thinking as an explicit component. Of course, there is a cap to how much the university can teach, but, imagining if the total curriculum were a loaf of bread, perhaps as a bulwark and a more robust (but nevertheless futile) endeavor to futureproof, the university ought to remove a few slices and replace them with some that guide students through the torrent of information, providing suggestions on how to find their bearings within. If the institution does not intend to follow its natural cycle of birth, decay, and death privy to the genesis and developed obsolescence of extra-institutional ideas, its salvation lies in a balance between the contemporary and the timeless. To survive, the particular institution will appropriate the radical and the new; perhaps more importantly, and more valuably for its graduates, it should also augment its enduring lesson – how to think critically.

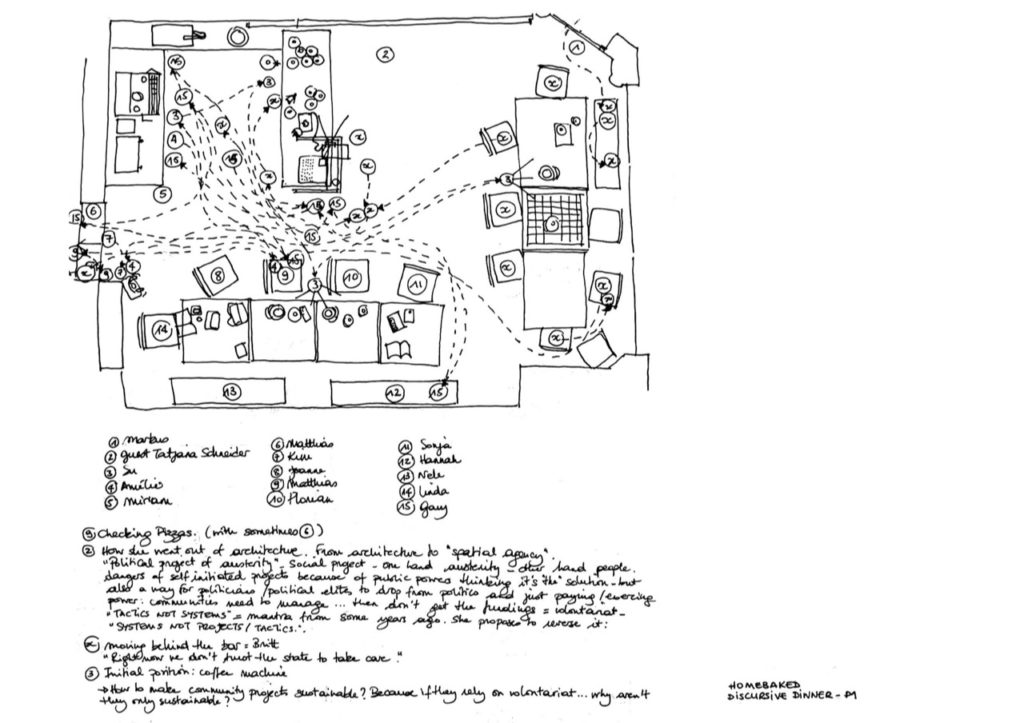

In a world of ever-increasing, easily accessible information, to aid students in developing their own filters, perhaps the university ought to revise its curriculum to include more critical thinking courses.

In learning to think critically and understanding what it is to struggle through the framework provided by the institution, one learns how to think architecturally. This – architectural thinking – is the summation of the experience and curriculum of the diploma, and is perhaps its greatest enduring endowment; it is precisely that which maintains the diploma’s importance. Even if the student chooses not to pursue a career explicitly in architecture post-graduation, the lesson remains – in fact, more than that, it persists, structuring all thinking, consciously or not. This is evident in both architects and non-architects and in both designers and those who pursue careers in other fields. It is evident in classmates who pivot towards other disciplines but maintain the rigor they learned at university, it is evident in international firms whose design processes seem not unfamiliar from those learned closer to home, and it is evident in the workflows of public figures who graduate with architecture diplomas but choose other paths.

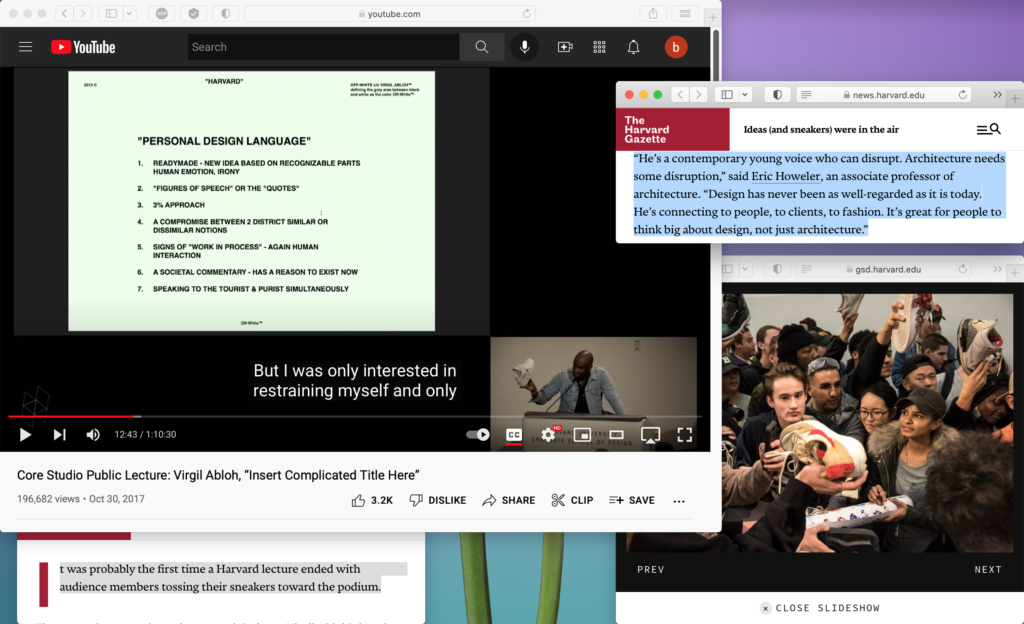

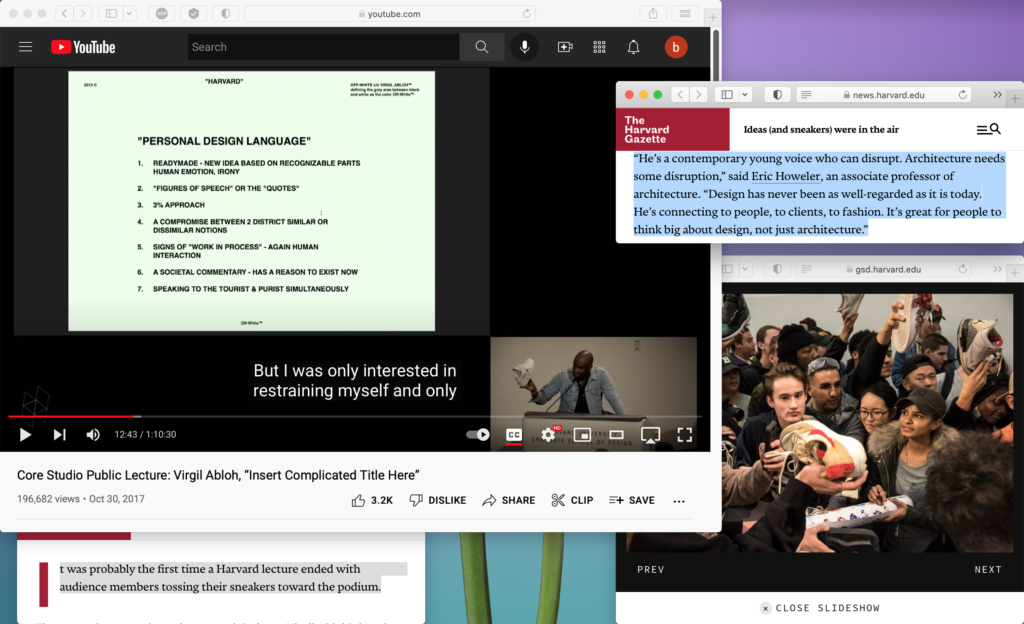

The methodology and immense body of work of the late Virgil Abloh is a prime example of the latter. Because though he may not have practiced as an archetypal architect – working for a prolonged period in a firm, as a professor, or in a traditional capacity of building buildings or writing papers – any cursory reading of his work or watching of his lectures reveals that he is indeed an architect through and through. His designs and his speech exude architectural thinking. In one lecture alone, he discusses developing a personal design language, using an incremental rather than radical approach to new design, and, in the redesign of ten of Nike and Converse’s most iconic sneakers, choosing to maintain the essential qualities of the sneakers’ forms while exposing their materiality and construction.4

The notion of a personal design language is so obvious to the average architecture student – from Palladio, to Gaudi, to Le Corbusier – that it is practically assumed. The conservatism implicit in an incremental approach is profuse in the practice – the de facto method in a discipline so immersed in code and context. And maintaining the essential qualities of a thing or setting while exposing materiality is yet another pillar of the architectural education – it speaks of Ando, in some ways of Gehry’s first house, and of Kahn. Abloh spent less than a decade in the conventional architectural discipline. He did not intern without pay for a starchitect, learning code and correspondence, obtaining a license, and rising through the ranks. For this reason, most would call him a fashion designer and few an architectural one – for what are his credentials? What makes him an architectural designer? His credentials are his diploma – not as a rubber stamp, but rather the years of active learning and struggle that constitute and result in a diploma. It is this experience that taught him to think architecturally, providing him with a systematic methodology, a holistic approach, and a beacon through the miasma of interdisciplinary uncertainty. It is precisely this that makes him an architectural designer.5

“Architecture, I used to think, was building buildings, but me navigating my way into this institution [IKEA] that provides furniture to real people — if I can bring an ounce of an idea, that’s already an idea.” – Virgil Abloh

Virgil Abloh is a stellar standard for the future of architectural education for two reasons. One, what is aforementioned as obvious to the average architectural student is absolutely not to the average person; his work makes architectural thinking both more accessible and readily accepted by those outside of the discipline. Two, he reveals the possibility of practicing as an “architect” both beyond the institution and as a result of it. On the one hand, the teenager with a passing interest in fashion design, aware of Abloh’s ties to architecture and through watching some of his interviews, is exposed to architectural ideas, potentially becoming interested in an architectural education. The diploma they may then pursue, although held behind a curtain of high tuition, is – cynically or not – validated by Abloh’s holding of one. On the other hand, the architecture graduate who finds themself embittered at their limited career possibilities and the imposition of ever more time requirements, fees, and other institutional and systemic blockades in the pursuit of a license – perhaps wonders, given the accessibility of information online today, if it was at all worth it after all. The example of Abloh elucidates that, if not financially, spiritually it was indeed worth it, for it holds the potential to be a through line through the pursuit of any possible future interest.

Much as readers of John Maynard Keynes’ 1930 essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren” may have been reassured by his attempts to counter contemporaneous pessimism in an era of great change, one should neither be paralyzed by nor resent this bewildering time. One should realize that it is precisely this institutional architectural education created and informed by extra-institutional resources that will hold one in good stead, continuing to be relevant in some form or another, and precisely the foundation provided by this education that will guide one through a future of learning and interdisciplinary explorations. Architects, architectural institutions, and students often lack disciplinary confidence because of imposed mental limits to what they are and are not allowed to do and capable of doing, restricted by an implicit agreement on what constitutes “architecture” and “the diploma.” They need not be troubled by this and they need not weep. As independent methods of learning give shape to popularly accepted ones, they need not fear what they do not know, for what they do not know will give shape to what they do know – and what they do not know is in fact what will give them ever more agency.

1 As opposed to extra-institutional learning as an act of rebellion against prevailing orders and so on, which, though occurring, does not take up the majority of the cause.

2 “With this surfeit of content, is this not enough to render the diploma obsolete?”

3 At the time of writing, in March 2022, SCI-Arc is very much faced with such a do or die moment, its relevance put completely in question in the wake of the publicizing of its litany of financial scandals, abuses of power, and other intensely immoral actions, past and present. The fact that this new student movement demanding accountability arose from: 1) A video published by the institution to its YouTube channel as part of its ongoing campaign to maintain media relevance that also attempts to be educational material for its students and the community at large; 2) Student protests, the publicizing of students’ traumatic stories with SCI-Arc faculty, and a student-organized town hall concurrent with extra-instutional organizational work by Instagram meme accounts like @dank.lloyd.wright and a group of SCI-Arc alumni points to the unavoidable interplay and inextricable connection between the institution and its other in the evolutionary process or collapse of the institution.

4 “Core Studio Public Lecture: Virgil Abloh, ‘Insert Complicated Title Here’”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-qie5VITX6eQ

5 And, arguably the kind of drive and personality that led him to pursue an architecture degree in the first place.

Boneless Pizza is a designer, writer, artist, and DJ based in Los Angeles. Their design work blends Lacanian theory, linguistics, pop cultural criticism, and digital media in the creation of parafictional worlds meant to investigate the contingent nature of the built environment.