Amy Perkins from CARTHA caught up with the author of “Super-designed World” Ciro Miguel to reflect on his submission for “The Possible Progress: Answers Series” that was published a week before the global lockdown. This conversation navigated the notion of progress as inherently paradoxical, questioning these nuanced differences through the medium of landscape photography.

AP

You are an architect, teacher, photographer and visual artist currently studying for a doctorate at the ETH. Your work as a visual artist is often about bringing objects as well as ideas into a close and sometimes uncomfortable proximity. We invited you to submit to the magazine in 2019 on the topic of progress to which you submitted an epic photographic essay describing our super designed world. The series of photos you assembled was published just before the whole planet went into a global lockdown, which is part of the reason for us revisiting it through the lens of hindsight today.

Maybe you would like to begin with a brief description of what you were trying to say when you put the original submission together.

CM

The idea of this photo essay was to discuss the domestication of the planet through fragments of man-made environments. Generally, the images show juxtapositions of different temporalities, programs and scales. In a sequence, it is a critical narrative about the meaning of progress in different parts of the world through disordered samples of urban patchworks that happen anywhere.

AP

Maybe we can talk a bit about how you work: I imagine that you have an incredible archive. When you receive a task such as this one is it about sifting through your images and putting together a story, or do you go out fresh with your camera to try and capture the idea?

CM

My approach to photography is pretty much that of an architect who takes pictures as a way to investigate and formulate ideas about cities, architecture and people. Therefore I keep a big and chaotic archive, almost like a diary of images taken anywhere, anytime, with different cameras and film. By looking at this very broad collection, one starts to realize patterns and recurrences that can be organized in particular ways in order to tell specific stories. In addition, I also keep an archive of old photographs, maps, postcards, drawings and projects that I constantly use as reference.

AP

They are all photographs from your own personal archive, photographs you took yourself – how did you go about making this particular selection for the publication?

CM

They were imagined as images of the Anthropocene, images that contain traces of human activity, for better or worse. The selection itself started with a Luigi Ghirri text in which he writes that “Reality is being transformed into a colossal photograph, and the photomontage already exists: it’s called the real world.” The photographs have clear oppositional qualities or spatial discontinuities, like in a photomontage: an artificial forest next to skyscrapers, tennis courts next to a container port, a monumenta reservoir in the mountains, an ordinary swimming pool on a hill, etc.

AP

So we are looking at extremities of human action in and upon environments?

CM

Definitely. I was always fascinated by the idea of domesticating a wild river or constructing on top of a mountain. However, these extremities are not exceptional experiences, they are part of our everyday life.

AP

Part of the reason we are doing this interview is because the world has changed beyond what anyone could have imagined, due to something tiny and invisible to the naked human eye. We are revisiting these works to see whether your reflections on them have changed. Do you feel differently now about the result?

CM

My take on the subject was generally optimistic, with a certain thrill for these moments of humankind as a geological power, transforming nature into an inhabitable environment. But after the latest events this initial optimism has turned into melancholia.

In the current context, it seems necessary to question this idea of dominance of nature or landscape, and embrace some sort of coexistence, in which we are not in the centre of everything and nature is not only the backdrop to our own actions.

For instance I was reading recently how in Ecuador a law was passed in 2008 to give its mountains, rivers, forests, and air constitutional rights. In other words, it completely changes the current notion that a mountain is only a resource to be exploited or a location to build hotels.

AP

What was your take on the notion of progress when compiling the essay?

CM

My critical look at the notion of progress is that it intrinsically has side effects. When a river is rectified and controlled in a concrete channel, it is a severe intervention, with many ecosystems altered forever. The pictures hint at this ambiguity: in this “super designed world” there is also death, ruin and decadence.

AP

What’s quite special about this photo essay is that it allows so many different readings. When I first saw it there was this kind shock at the scale and the types of human activity in the most extreme places. Then also a strange feeling of joy about the juxtaposition, the fact that, yes we are everywhere but we’re also intertwined with everything else. When you are in a good mood you can see the beauty in these situations, but when you are feeling disheartened about the state of the planet they can also feel totally overwhelming.

CM

As architects I think we all feel these contradictory emotions towards these images. Building in such harsh environments feels like the pinnacle of the technique, of civilization, to be able to transform an environment and make life possible. The Brazilian architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha likes to say: “the question of architecture is to build the habitability of nature”. However, it also makes you question whether this is really the best that we can do. Is it possible to reinvent new ways to live?

AP

Your work is so bound with the idea of going somewhere to be able to make these compositions, these real life montages, and yet during the past few months global travel has been greatly reduced. Do you think that the way you work will have to change?

CM

Not being able to travel brought me back to collecting images and to travelling through books, and to taking pictures of pictures.

As a matter of fact, the photographer that I mentioned before, Luigi Ghirri, did not travel much in his life and most of his pictures were very close to his home. And therefore one can look actively and critically at many everyday situations that normally go unnoticed. During the isolation in São Paulo, for instance, I started to be much more attentive to my surroundings because I was basically confined to a block in the city and I made some interesting discoveries.

AP

I was going to ask if you would have done it differently, were you to have been given the task today, but it seems like you almost have. To try to find these juxtapositions from the essay within the confines of a city block is a great exercise.

CM

Yes! I was almost angry at myself for never having paid enough attention to these things before, the beauty of construction sites, sidewalks, corners and gardens, that have always been there, just a few steps away from my house.

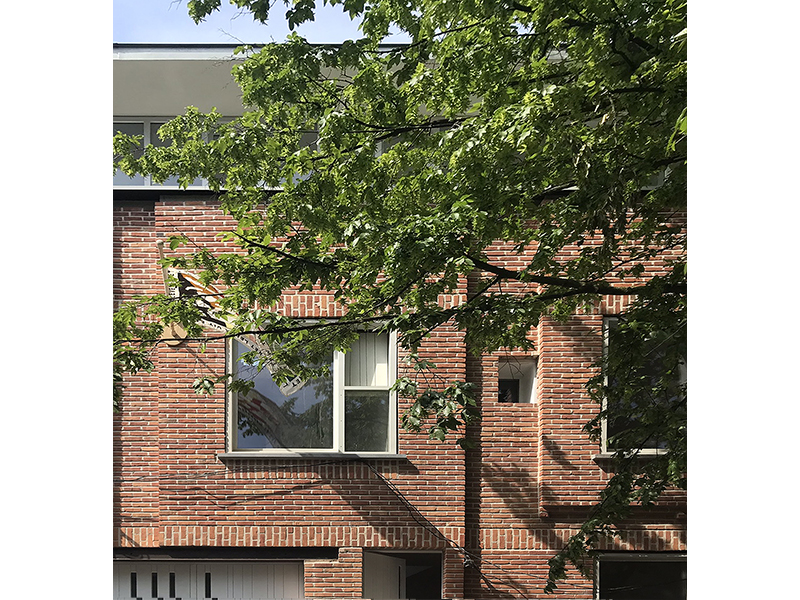

I also developed a connection with the neighbours, following their routines everyday, even though the closest building was 100 metres away. Differently from European cities, where buildings are mostly close to each other, in some areas in São Paulo neighbors cannot easily communicate across verandas or common courtyards. For this reason, I took pictures of them with the camera adapted to a pair of binocular, a home-made invention.

Isolation in São Paulo, Ciro Miguel, 2020.

AP

Coming back to the Ghirri quote and the idea of seeing the world as a montage, in some of your other work, you cut out images, placing them next to one another to create something new. There is an element of design in all your images, whether that is from montage or simply the composition of the photograph itself. What I worry about is when we rely solely on found images you remove yourself from that creative act.

CM

The photographer Bas Princen always says that a “good image” is in the lineage of other images, a good image is always connected to previous ones you have seen or will see. Sometimes a montage can be very contrasting, and sometimes very subtle, just enhancing a situation which is already present. All of the images we produce are manipulated and constructed, so I think that the method is the same.

But the so-called real world is way more dramatic and epic than anything you could actually imagine. For example in the last image, the one of the hotel on the mountain summit, many people believe that it is not real, and it really does look like a montage.

AP

What or who do you refer to? What would you say is your lineage?

CM

I have a real fascination for postcards, anonymous photographs and maps. Postcards are anonymous ordinary artifacts that portray subjects ranging from the extraordinary to the extremely banal, from the architecture icons to the everyday, from pyramids to roadside motels’ swimming pools. In the case of anonymous photography, the scenes are often composed in a way which allows them to tell very different stories of these emblematic architecture, buildings, and cities.

AP

So is that a big part of your work of, collecting and visiting archives to make yourself kind of a backdrop?

CM

Yes, I spend a lot of time casually image-hunting in online archives, libraries and old magazines.

AP

In your text you talk about the conversion of the megalomaniac and the everyday. Your work on the São Paolo Biennale focussed on the everyday, yet your photo essay is anything but the everyday, it talks more about megalomania. Is this oscillation between the two always on your mind?

CM

There is an interesting interrelationship between the megalomania and the everyday. For instance, in the São Paulo Biennale one of the works at Sesc 24 de Maio was about the consumption of water. This intervention, designed by EMI, was located in Sesc’s bathroom and it questioned how daily routines of body maintenance, like washing hands, can have a deep impact on the planet. Another work, by Andrés Jaque, connected architecture’s obsession with transparency with dystopian landscapes of extraction of ultra-clear glass materials. So in a way, the small scale of the everyday and the big scale of infrastructure are deeply connected.

Currently I am investigating pictures of colossal infrastructure projects through the presence of ordinary people in the images. Besides their compositional role as ‘human scale’ to reinforce the bigness of the architecture, my interest is to discuss who were in fact these invisible individuals and how their everyday tales can challenge narratives of architectural history.

AP

Do you think the visual essay as a social or anthropological research method is an underused tool by architects?

CM

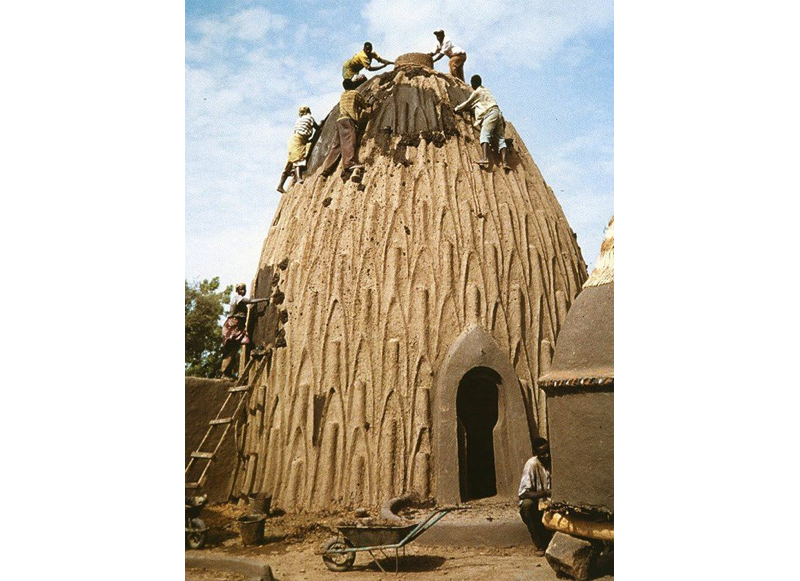

Perhaps. This is actually the topic of my phd at ETH, to look for alternative stories of mainstream modernism, to expose what the monumentality of modern architecture imagery tends to conceal: the marginal characters, the maintenance routines, the collectiveness of construction, ordinary events, the juxtaposition of the archaic and the modern. These images, taken by photojournalists or anonymous photographers were not under the scrutiny of architects, so by looking at them, one begins to find stories in opposition to the literature you would read about this particular building or period.

Another visual essay I’m working on is about the images of the land clearings at the initial phase of Brasilia’s construction, the early displacement of earth for creating the city. In all these scenes there was no sign of the architecture as we know it today, just tractors, trucks and the vast territory that the architects insisted on calling a “desert”. However, by looking at the photographs, one can see the physical reality of that amazing landscape with a rich fauna and flora. The images are very ambiguous as to whether it is construction or destruction.

AP

And my guess is that it is both. It is the destruction of a habitat.

CM

Exactly. It was seen at the time as an image of progress and development. The word ‘progress’ is constantly repeated during Brasilia’s construction, reinforcing the idea that a modern city could bring ‘civilization’ to the country’s hinterland. However, looking at the pictures today, progress seems much more like a story of destruction and violence.

AP

This idea of finding archive images where the focus is not necessarily the architecture or humans, but is activity, especially when you are an architect, you start to see yourself and your work as parts in much greater scenes, you start to read the architecture as part of the background to these scenes. It gives you this feeling of being just one of the players in a rich habitat.

CM

Definitely, this is very interesting. By pushing the architecture to the background, buildings allow these stories to unfold, supporting the unpredictability of life.

AP

But there’s also a problem in the language architects use as well. Describing some things as “deserts” for example, the words conjure ideas of emptiness, of a lack, which leads to the opinion that these places are somehow less worthy.

CM

And it’s actually a myth. Rainer Banham’ text Scenes in America Deserta describes the desert as full of life, as a very rich environment. Architects tend to use these words “desert” and “tabula rasa” to justify their projects, but there is no neutral landscape. This exploitative, destructive thinking is so embedded in our western culture, and architecture is not immune.

By looking at the photo essay after all the changes in the world which followed, it seems we have only one story being told, that of progress, of advancement. However there are other ones, from those who have always been marginal to these processes and have different perceptions. Perhaps the answer to the planetary crisis will come from them.

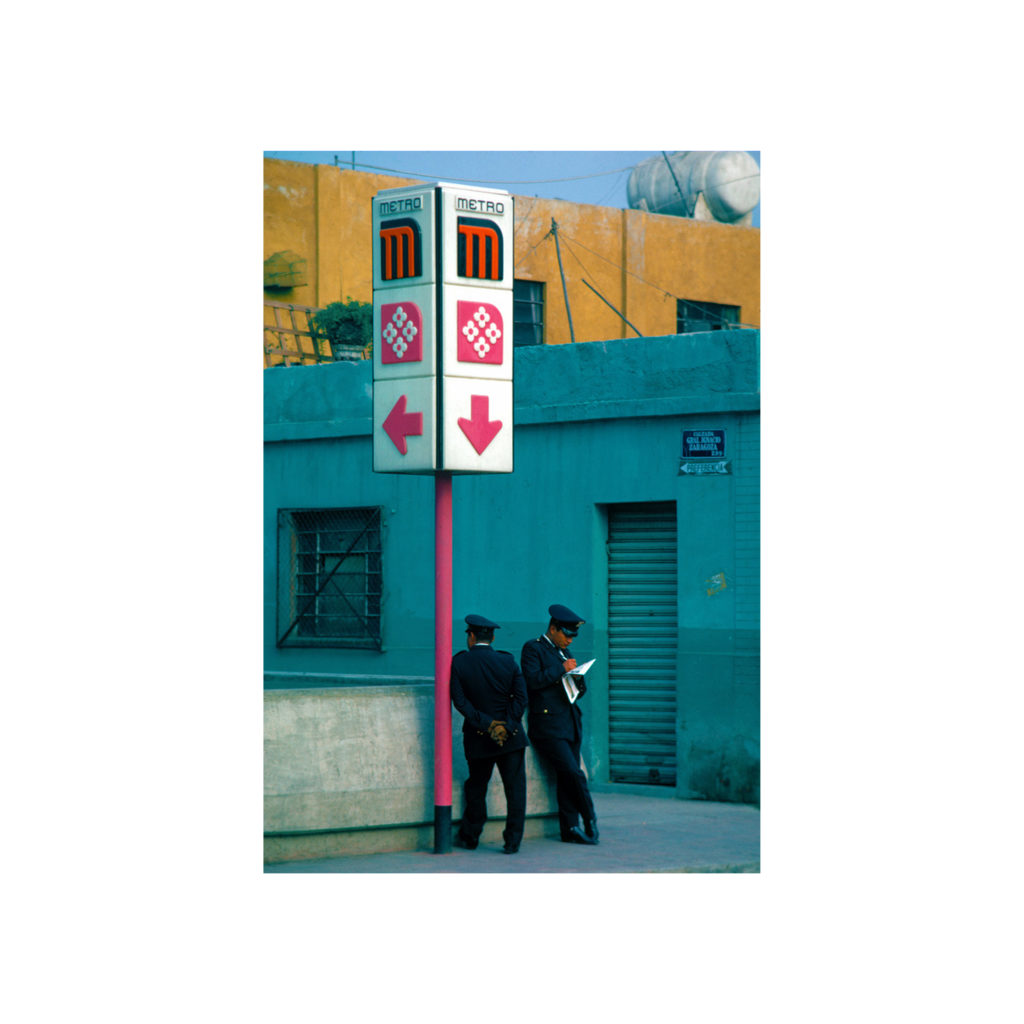

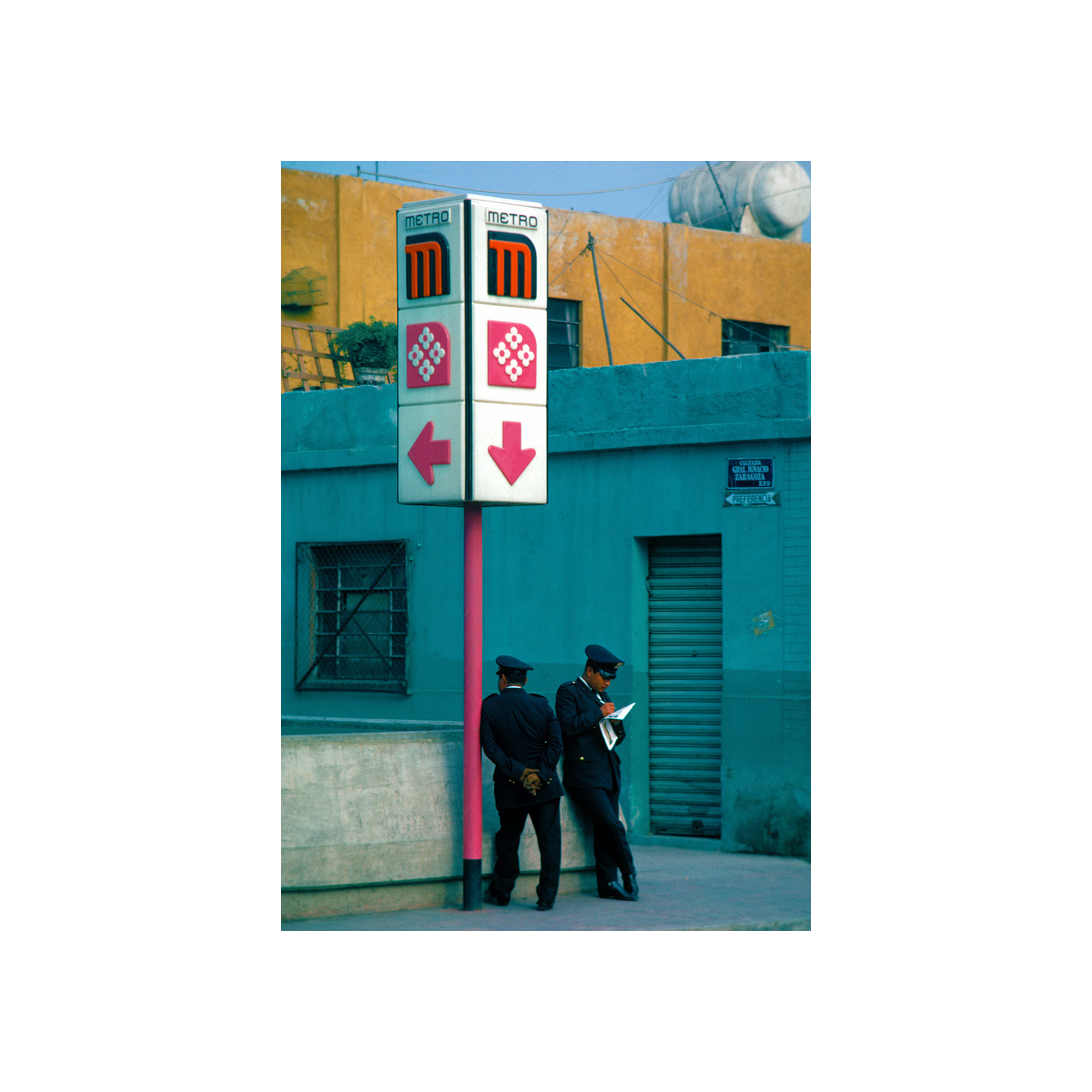

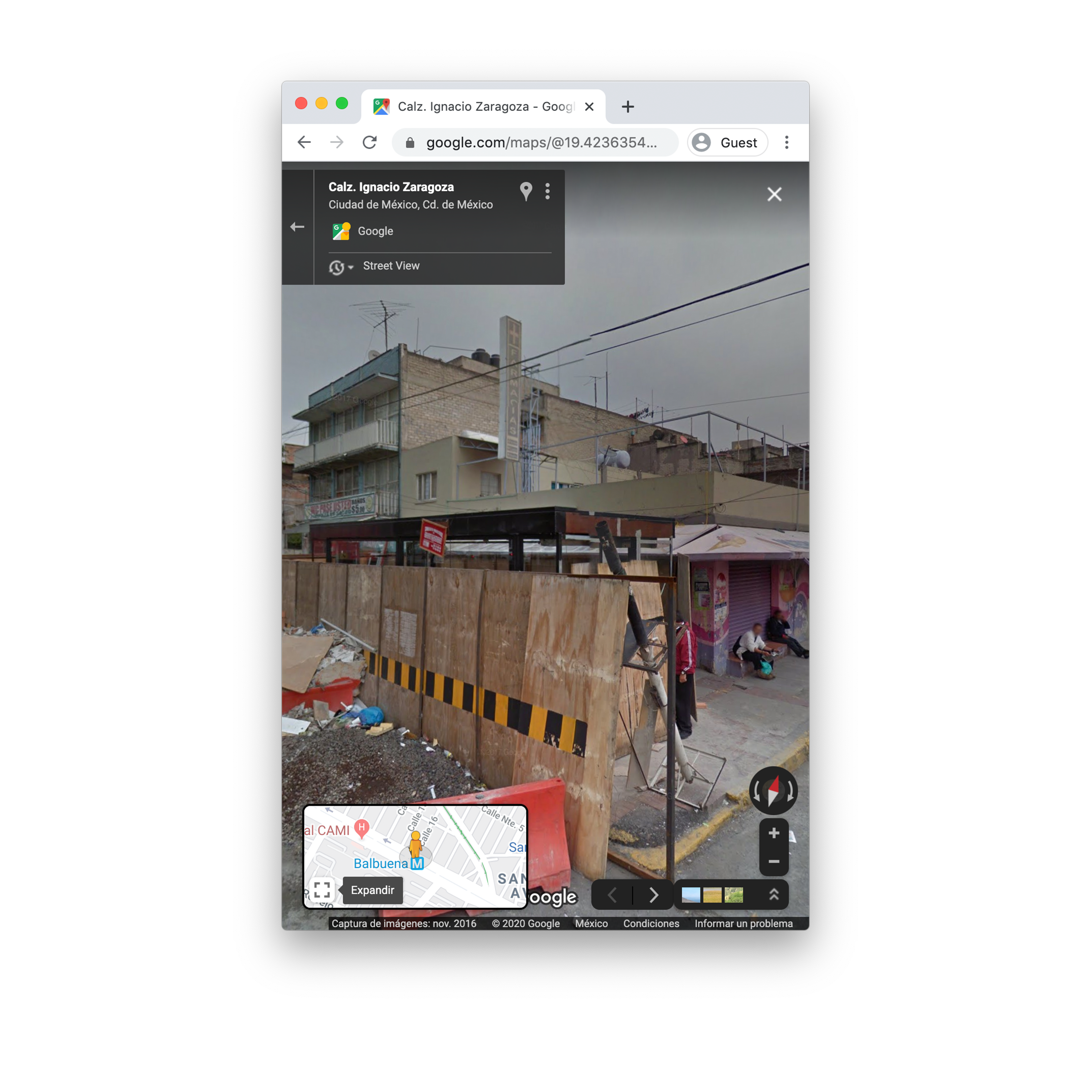

In 1969, the British illustrator Robin Bath took a photo of one of the entrances to the Balbuena station of the Metro Line 1 right after its inauguration, at the corner of Calzada Zaragoza and Calle 16 in eastern Mexico City. This photograph is from the archive of Lance Wyman who led the identity design for the Metro. The Metro system was supposed to open before the 1968 Olympic Games but it was not finished on time. In the foreground, the original sign post for the station stands with its pink flower pictogram. In the background, there are two buildings: one with fenced windows and a door shutter; and a second one with a plant, a birdcage, a water tank, washing lines and power cables on its rooftop. The buildings appear in bright, contrasting colors, and it would not be surprising if they were painted specifically for the photograph, Potemkin village-style, as it was done in other zones of the city during the Olympic games a year before. The only two people in the shot are two policemen who, from their extremely relaxed posture, one can assume were unaware the photo was being taken.

In 1969, the British illustrator Robin Bath took a photo of one of the entrances to the Balbuena station of the Metro Line 1 right after its inauguration, at the corner of Calzada Zaragoza and Calle 16 in eastern Mexico City. This photograph is from the archive of Lance Wyman who led the identity design for the Metro. The Metro system was supposed to open before the 1968 Olympic Games but it was not finished on time. In the foreground, the original sign post for the station stands with its pink flower pictogram. In the background, there are two buildings: one with fenced windows and a door shutter; and a second one with a plant, a birdcage, a water tank, washing lines and power cables on its rooftop. The buildings appear in bright, contrasting colors, and it would not be surprising if they were painted specifically for the photograph, Potemkin village-style, as it was done in other zones of the city during the Olympic games a year before. The only two people in the shot are two policemen who, from their extremely relaxed posture, one can assume were unaware the photo was being taken.

Bild Wissen Gestaltung, to which our research project was affiliated, represented a large and unusually interdisciplinary research project and therefore offered the opportunity to examine such a research project from within: What influence does space have on knowledge production? Which spaces and spatial qualities are required to develop new knowledge at the interface between the disciplines? We placed particular emphasis on the question of collaboration: What effect does space have on collaboration within and between existing teams as well as on the emergence of new constellations? A specific challenge was to find spatial conditions that promote collaboration but also offer opportunities for individual retreat. In order to investigate these questions empirically, we developed a novel experimental and interdisciplinary method for the investigation and design of space, so-called ‘experimental design-based field research’. For this purpose, a research area of 350 m², the Experimental Zone7, was created for forty scientists, which was redesigned and rebuilt approximately every two months over a period of three years. A total of eighteen experimental settings was carried out and observed both quantitatively and qualitatively. In line with a practice theoretical approach, the materialized knowledge practices and routines, i.e. bodies and objects, were afforded special scrutiny.

Bild Wissen Gestaltung, to which our research project was affiliated, represented a large and unusually interdisciplinary research project and therefore offered the opportunity to examine such a research project from within: What influence does space have on knowledge production? Which spaces and spatial qualities are required to develop new knowledge at the interface between the disciplines? We placed particular emphasis on the question of collaboration: What effect does space have on collaboration within and between existing teams as well as on the emergence of new constellations? A specific challenge was to find spatial conditions that promote collaboration but also offer opportunities for individual retreat. In order to investigate these questions empirically, we developed a novel experimental and interdisciplinary method for the investigation and design of space, so-called ‘experimental design-based field research’. For this purpose, a research area of 350 m², the Experimental Zone7, was created for forty scientists, which was redesigned and rebuilt approximately every two months over a period of three years. A total of eighteen experimental settings was carried out and observed both quantitatively and qualitatively. In line with a practice theoretical approach, the materialized knowledge practices and routines, i.e. bodies and objects, were afforded special scrutiny.