Editorial

CARTHA

THE POSSIBLE PROGRESS “L’amour pour principe, l’ordre pour base et le progrès pour but” “Love as principle, order as basis, progress as goal” –Auguste Comte The Positivist Stage, as stated by Comte, marked the entry into an era when, due to gradual but constant scientific developments, increasingly accurate predictions of the future could be done. […]

THE POSSIBLE PROGRESS

“L’amour pour principe, l’ordre pour base et le progrès pour but”

“Love as principle, order as basis, progress as goal”

–Auguste Comte

The Positivist Stage, as stated by Comte, marked the entry into an era when, due to gradual but constant scientific developments, increasingly accurate predictions of the future could be done. But this entry has also prompted a new condition, in which the consequences of the steps being taken towards a certain destination contained the potential to lead mankind into a more precarious situation than previously. This perception was enhanced as well by a critical approach to history during the beginning of the XX century. Walter Benjamin pictures progress as a wrecking storm 1. Comte defines progress as the “goal”. But can one understand progress without knowing which, what, for whom the effects and goals are and pertain?

SCIENTIFIC ASSUMPTIONS AND CULTURAL CONSTRUCTIONS

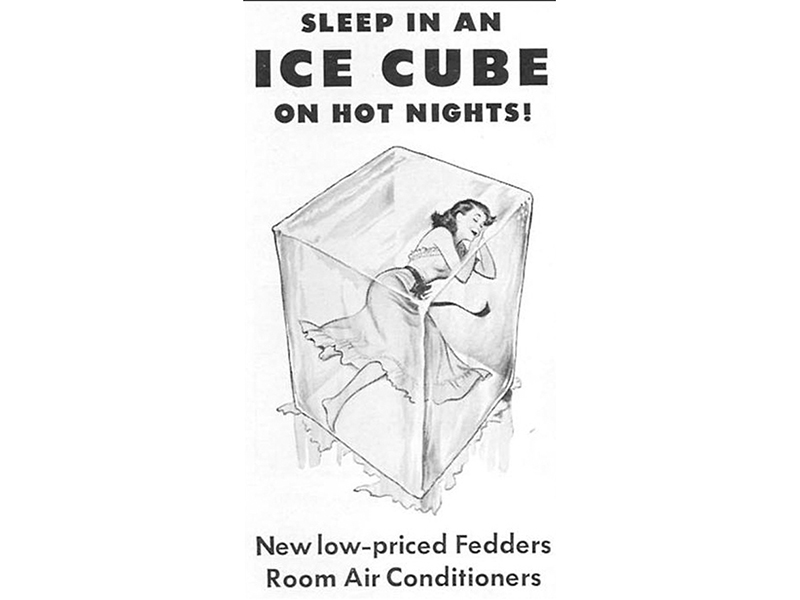

During the past two centuries, narratives around the future developed into the offer of scenarios containing possible solutions to current problems at a given moment in time. The notion of progress became a tool for the definition of desired behaviours, implying either that the future will be necessarily better or that a certain course of action will lead us to a worst-case scenario. It seems difficult to reach an agreement on which ideals we should aim for but, regardless of the ideas behind a certain position, technological progress is mostly seen as one of humanity‘s great hopes.

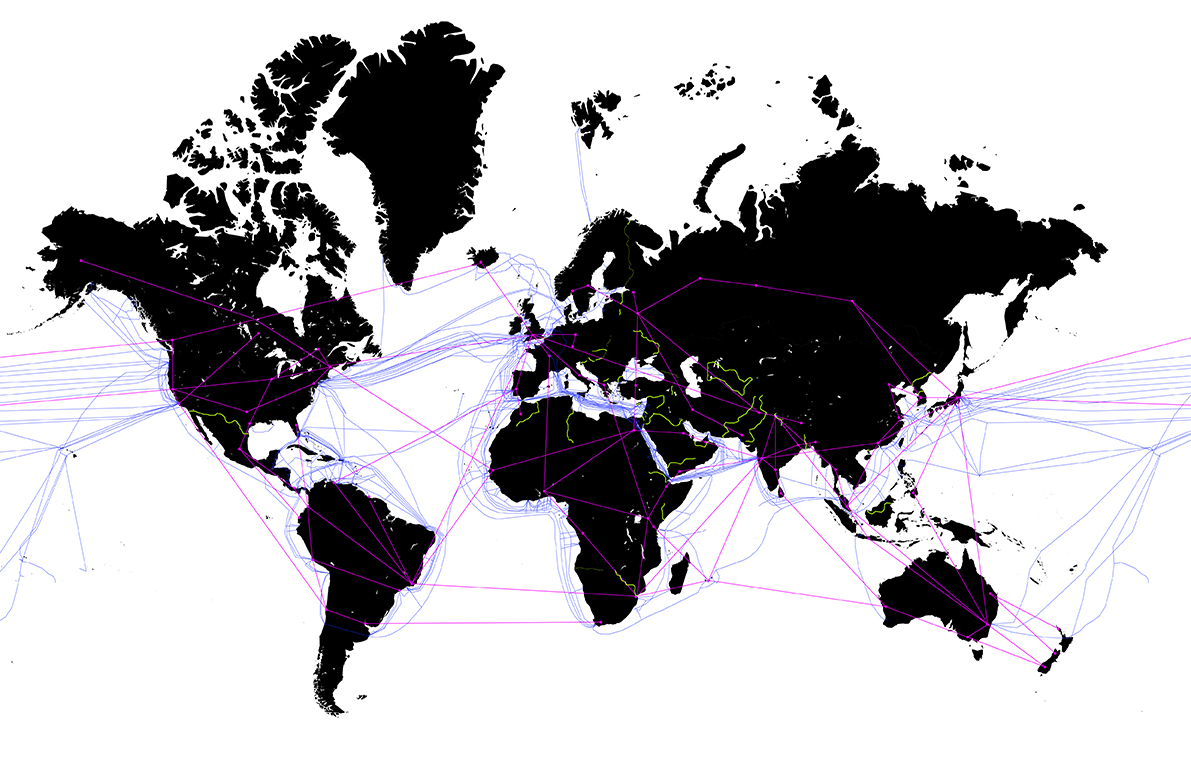

Though scientific advances definitely influence the notions of progress, progress itself seems to be far from scientific. Rather than a straight line, freed from “the silence of envy, or the caprices of fashion,” progress is a rather sinuous, fluid string that fluctuates according to the tides of political intentions2. Utilitarian notions of speed, amount, range, volume, brightness, size, etc. keep being revisited and reappropriated, according to the prevalent views of the day on the correct direction to move towards, pushing habits and conventions along with the sliding shell of a fragmented cornucopia. On October 24, 2003, Concorde flew its last commercial flight. Ultimately it was retired not because of the catastrophic accident in Paris in 2000, not because it was not profitable and consumed gargantuous amounts of fuel, nor because it could no longer fulfil its initial functions, but due to the subsequent unbearable noise caused by the breaking of the sound barrier. Its supersonic nature—heralded as the future a mere 27 years earlier—ended up being the reason for its failure.

This shift in perception of noise is closely connected with the evolution of the broader political and technological landscape. After all, the effects of the supersonic jump have not changed (neither have the fuel consumption of the planned costs per trip). What changed was the relevance and scope of the voices of the people and property affected by Concorde’s flights. New media brought enhanced visibility to anything witnessed by anyone with a device to hand. It rendered governments either liable or responsible for ensuring justice, first in the compensation for the damages and, later on, for assuring the comfort and quality of life of those affected. This very symbol of British design and scientific excellence in an era obsessed with speed and distance was sacrificed by the political forces in the name of a society focused on comfort and safety.3

STATIC VS. FLUID

Shifting goals means shifting notions of progress. But progress—since the Enlightenment, at least—inherently contains the paradoxical nature of change being the key for the development towards an improved or more advanced condition. How does this implicitly fluid characteristic relate to the built environment?

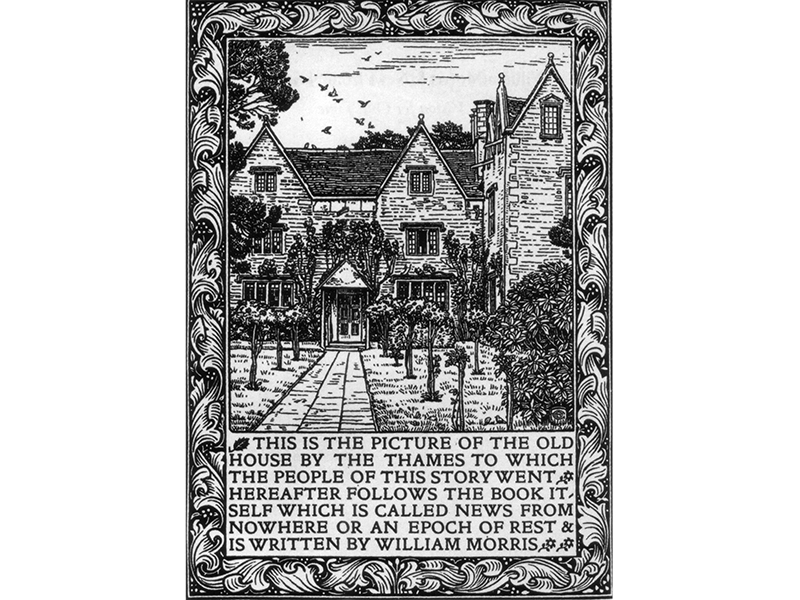

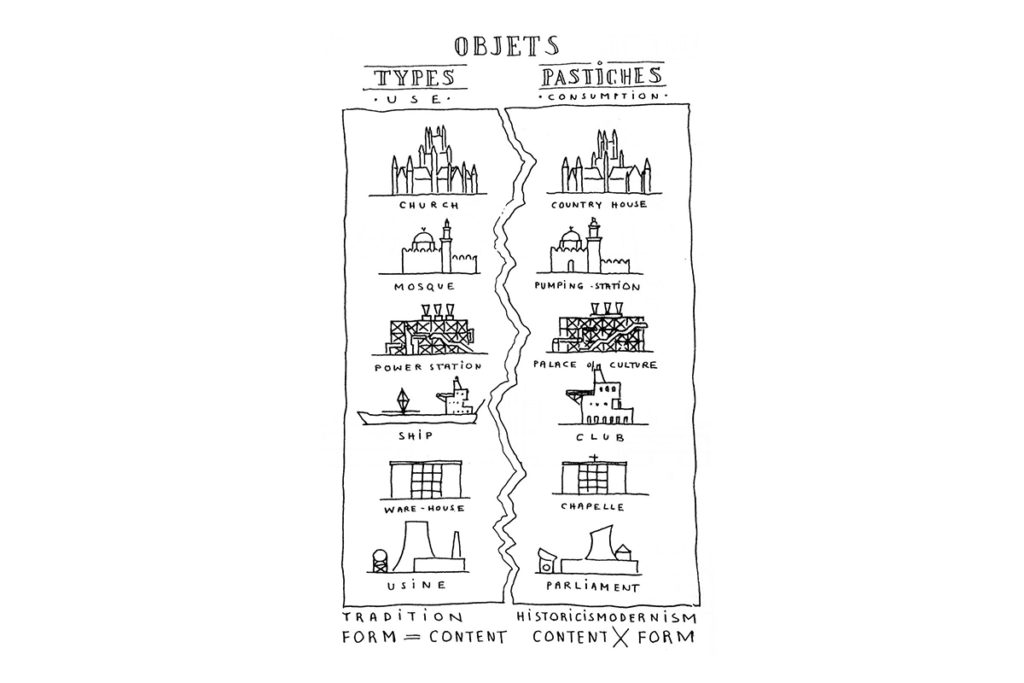

The Positivist Temple in Porto Alegre, Brazil, a remnant of the church based on Comte’s semi-lunatic proposal for mankind, serves as an example of the volatile nature of the notion of progress: it borrows its typology, structure, form, materials, function and identity from the Neoclassical churches built at the time. Though Comte was aware of the non-linear character of the stages, pointing out the necessarily conciliatory nature of Positivism, the ambiguity in the architecture of a building which is supposed to be the embodiment of progress, seems to go beyond the acceptance of said ambiguity, rather questioning the possibility of progress itself.

THE POSSIBLE PROGRESS

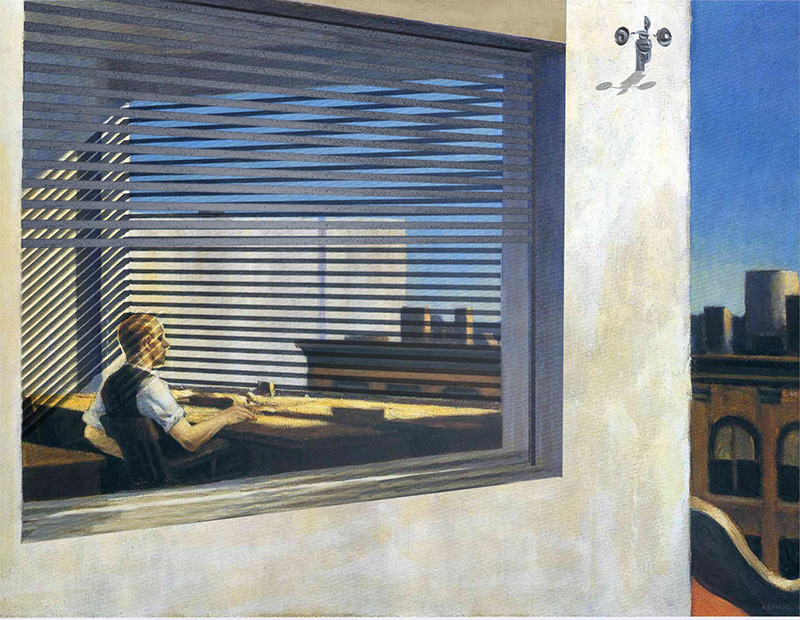

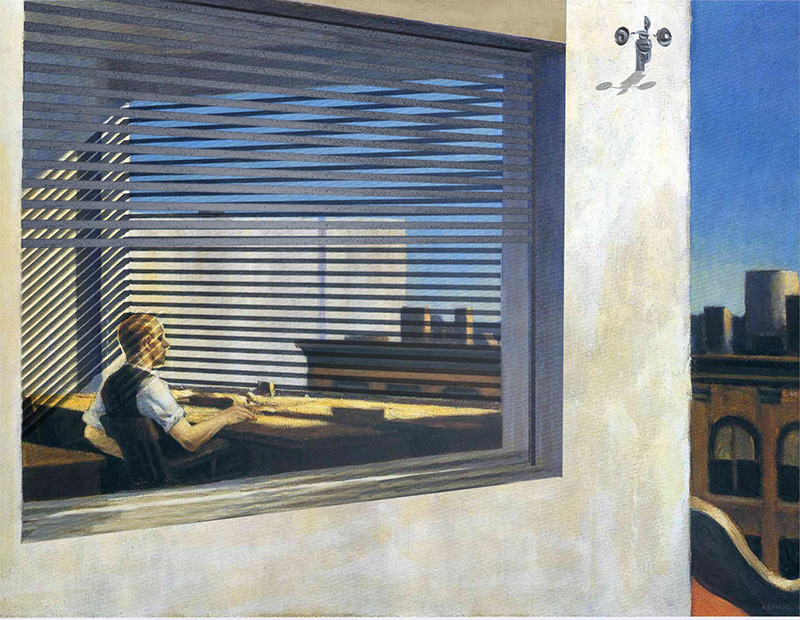

Perceiving architecture as a synthesis of the ideals and technology of society, positions architecture as a privileged barometer of the movement towards disparate notions of progress at different times. Departing from this position, with the first issue of this editorial cycle, we present a current definition of possible progress, through concrete case studies, opinion pieces and visual essays.

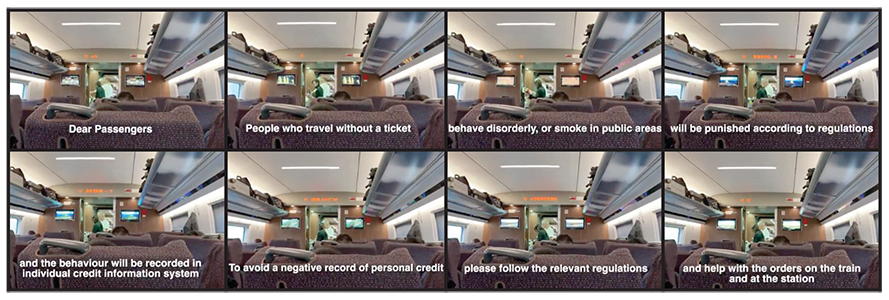

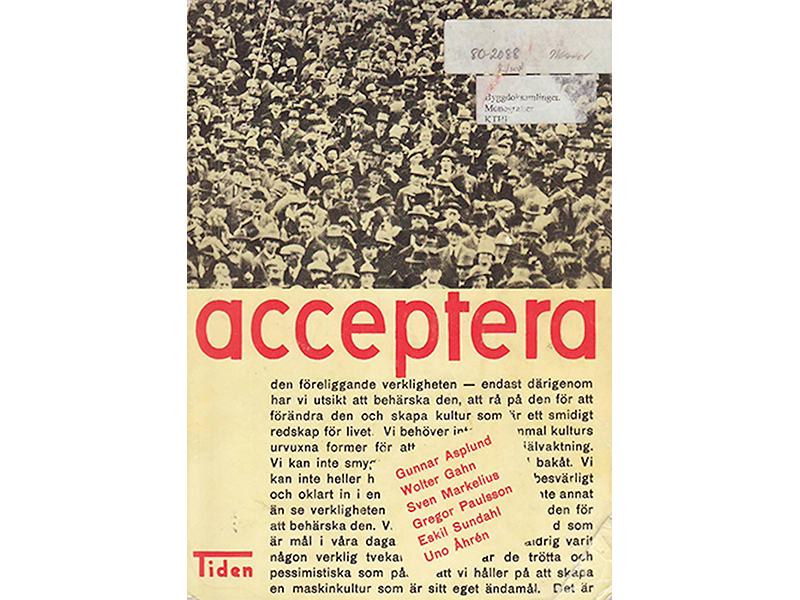

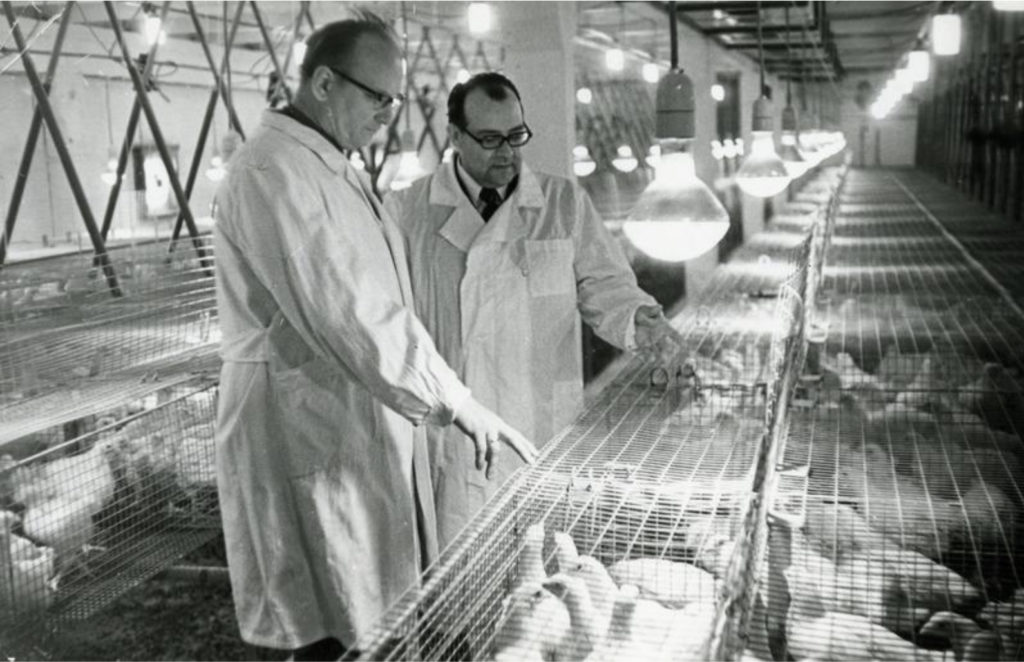

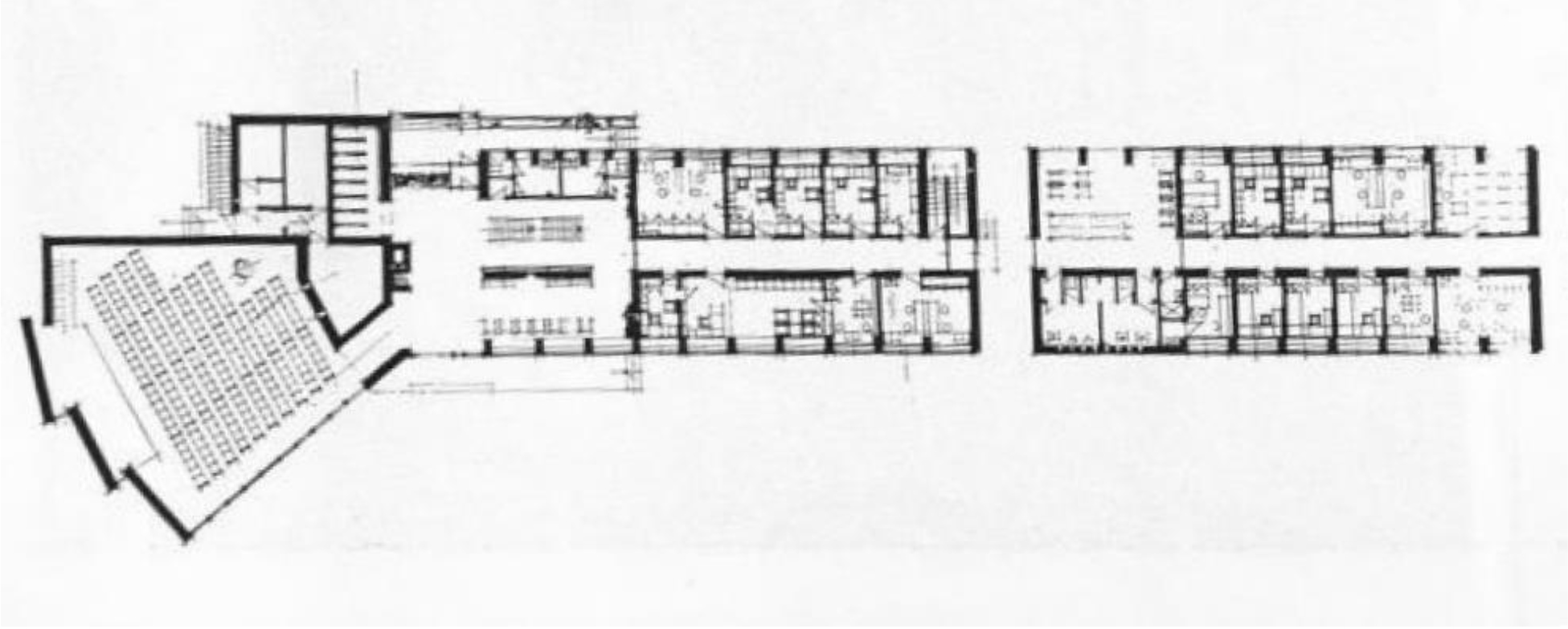

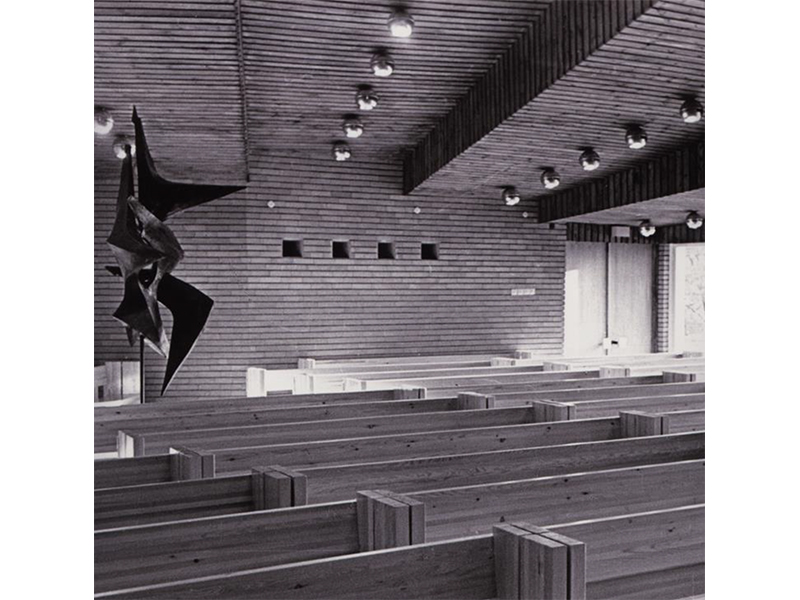

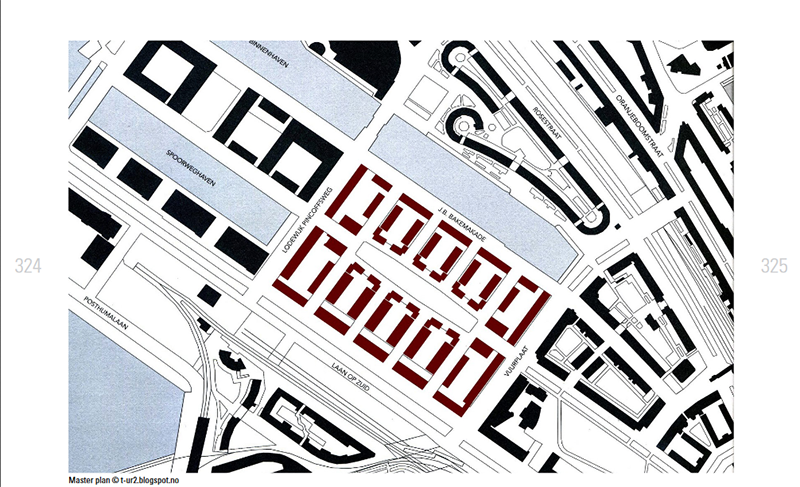

As a first case study, Max Kuo addresses Eisenmans’s view on media and its influence on architecture, picturing an impossible future where Eisenmann himself could begin his career in the 21st Century as a young chinese father. Continuing with Charly Blödel’s take on the ruin as implicit reference for the extreme present invites us on a critical tour from South Africa to OMA’s La Défence, with a stop in St. Louis, guided by Roberto Matta. Jeannette Kuo skillfully unweaves the relation progress has with building standards in Switzerland, questioning the current take on general comfort. Julia Dorn builds an argument for a contemporary Utopia, unfolding what now constitutes utopian thinking in the dimension of technological progress. In the same dimension, Chiara Davino and Lorenza Villani reveal the territorialization of social technologies that aim for efficiency but land in repression. Sara Davin Ommar and Felicia Narumi Liang, discuss the de-politicization of the swedish modern project of the 1930’s. Simone Marcolin and Diletta Trinari postulate Pier Luigi Nervi’s Burgo Paper factory as a Hymn to Progress. Adriano Niel discusses the opposite stances of the second half of the 20th century on the decay of the modern movement that shaped the contemporary discourse of architecture. Marta Malinverni and Alex Turner summon Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot to voice a sharp definition of progress. Sonia Ralston gives us an insight into the politics of progress in Soviet Estonia through the collective farm architecture developed in the pursuit of modernizing an establishing a scientific narrative for soviet agricultural industry. Finally putting biopolitics on trial, Simran Singh interrogates the image of domesticity in the form of mass housing.

The stances chosen by each of our contributors result in a critical survey of the current understanding of progress, highlighting complementary and contradictory aspects alike. These offer no definitive answers to the questions we posed in the call for papers. They nevertheless go beyond what we expected as each contribution plays a key role in positioning the responsibility on the decisions and consequences of all which progress might be, in our own hands as citizens of the global market society we are inserted in. On this sinuous route, flying towards semi-tangible goals, constantly looking back, the controls seem to be there for the taking, if we only wish to do so.

The Possible Progress will go on. This first issue lays the theoretical foundation upon which a series of sharp answers by key guests will be set, to be published during January, February and March 2020, and followed in April 2020 by a comprehensive design issue with contributions by some of the most interesting architectural offices worldwide.