Léon Krier is a unique voice in today’s architectural discourse through his commitment to developing a relevant and pragmatic theory of architecture based on his own experience and observations of architectural practice and opposed to the easy, abstract theorizing so common in contemporary architectural writing.

In your opinion What are the defining traces of contemporary society’s identity? Either in a global or local context.

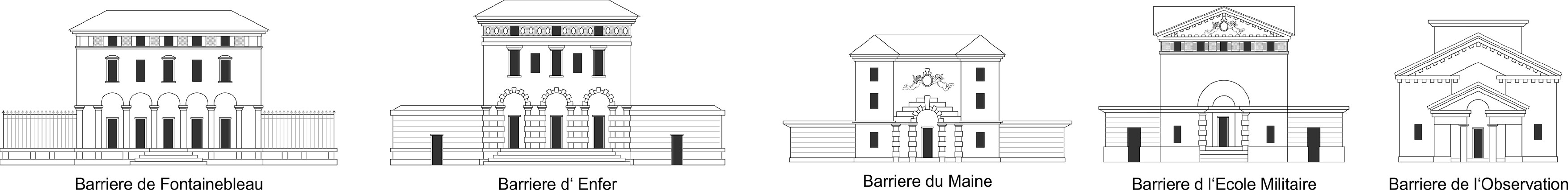

Dependance on fossil and nuclear fuels. most building materials, building forms and building processes and all urban and architectural designs are defined and dominated by them and so are their life span and their regular destruction through use, redevelopment and war action. Traditional architecture whether vernacular building or classical architecture is characterized by the use of local building materials. Only very seldom and only for extremely important buildings are building materials carted from distant quarries or forests. It is local building materials which mark the different architectural identities of the basque country or that of Tuscany or Bali. Synthetic building materials instead are products of analagous standarized industrial, fossil fuel dependant processes around the world. The products and their tectonic performances are the same around the globe, largely unifying architectural character and eliminating local identities defined by soil, climat and altitude.

It is tragic that more and more intelligent minds should at once be spellbound by that undecipherable, and easily manipulated, spirit of the age (zeitgeist) and so indifferent to the spirit of place (genius loci), the conditions of nature, of local climate, topography, soil, customs, all of them phenomena objectively apprehensible in their physical and chemical qualities.

How do you position yourself towards these traces?

Like it is the case for most human beings and societies also most of my private and public activities are defined by these energy sources. The practicing of traditional architectures and urbanism is rendered very difficult and sometimes impossible because building and town planning legislations, building culture generally, are part and parcel of an industrial ideology and mind set. Modernism and suburbanism rule supreme in state and government offices and academia.

My work demonstrates in theory and in practice how traditional architecture and urbanism are practiced and justified in a hostile institutional, academic and professional climate.

Is Architecture relevant to the building of the identity of a society? In which way? or Why not?

Traditional architectures and urbanism as shaped by soil, altitude and climate are instrumental in shaping the identity of societies worldwide. Traditional architectures around the world have over centuries evolved a great variety of building languages. unlike spoken languages, the elements constituting the traditional building vocabulary need no translation in order to be understood across borders and ages. They have universal validity, are part of technology before and beyond (transcending) mere historical deployments and meanings. Modern traditional builders or designers are naturally polyglot, can within no time decipher and master local idioma and realize structures in harmony with local traditions, culture, climate, soil, altitude. This cultural and technical versatility singularly contrasts with the dumb and blind modernist monoglottism, or rather illiteracy, imposing the same building types and mannerism across the planet, irrespective of culture, climate or geography. To build traditionally today is not ignoring the demands of modern life, on the contrary it is confronting the urgency to adapt to our planet means. It also answers one of the most deep aspirations of humankind, in these transient times even more relevant, “to belong”, by building and preserving a world of beautiful landscapes and splendid towns which imprint on our hearts for ever, places we can be proud to come from, to inherit and to pass on to future generations. To practice it, often against overwhelming peer prejudice, bureaucratic chicane and reigning fashionable fads, demands a challenging intellectual and professional determination.

The generalized use of fossil energies. the mechanization of human productions and relations and the use of synthetic building materials and air conditioning have temporarily led to ignoring the fundamental conditions on nature. The dominant modernist building typology and sub-urbanism, (the skyscraper, the landscaper, the suburban home and their massive proliferation in geographically segregated mono-functional zones) can only be sustained and serviced in conditions of cheap fossil energies. Very little legacy of that collective malpractice will survive the inevitable global consequences of oil scarcity and eventual depletion. The increasing human cost of oil-wars announce the end of the fossil fuel age and therefore that of the reign of modernism and suburbanism.

But i say that, given the present evolutionary stage of the human species, even if there were no limitations for any foreseeable future nor any political problems for the provision of fossil fuels, we should still go back to traditional forms of settlement, of agriculture, of industry, of production, of crafts, to those forms which were and remain the ones fitted to human scale, to our measurements and gregarious nature. We now discover when too many of our built environs have lost it, that human scale is an unrenounceable attribute of civilization not an obsolete luxury. No amount of connectivity, social media and virtual reality can be a permanent substitute for physical contact in social interactions and its corollary of succesful mix-use open public spaces..

Are you conscious of your role, as an architect, in the building of an architectural and social identity?

I am interested in architectural and urban forms of the pre-fossil-fuel ages not as irretrievable history but as a technologically, socially and artistically unrenounceable experience, as resources for the future. I am not an architectural historian and i have little use of that profession and discipline. I am, to be explicit, not practicing historical designs but traditional architectural and urban designs for modern societies around the globe.

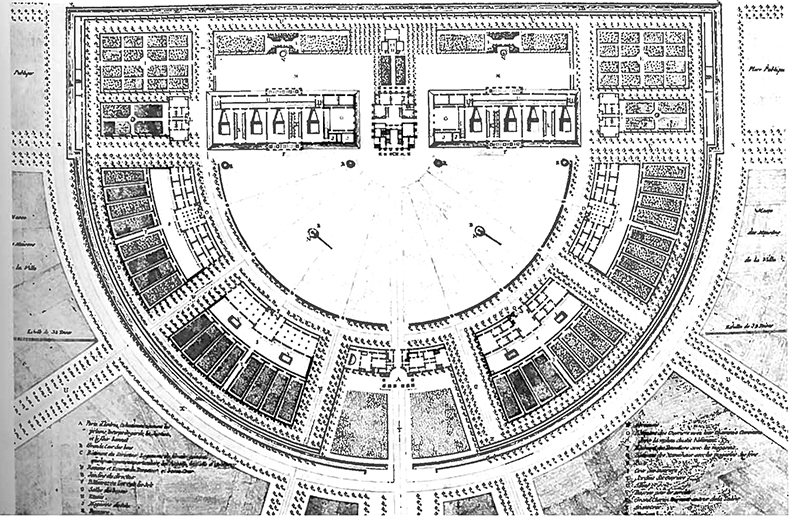

The traditional greek-roman-christian city is the universal model of the city for the open modern and democratic societies. It is the polycentric city of independant communities. Modernist zoning techniques instead result in territorial vertical of horizontal sprawl. They legislate the anti-city realize the atomized societies.In that sense the architect has the choice to participate in building or in destroying the modern democratic society.

The mission of planners and architects should be to look after the local culture and patrimony and work within the local parameters to preserve, rebuild and enhance their idiosyncrasy with new construction respectful or its context. There are plenty of new traditional urban and architectural projects under construction around europe and the americas. They are, like the Prince of Wales Poundbury project, entirely undertaken by private and individual initiative. Val d’Europe, Plessis-Robinson, Brandevoort, Lomas de Marbella club, Pont Royal-en-Provence, Knokke-Heulebrug, seaside, Windsor and Alys beach in florida, Paseo Cayala in Guatemala. In contrast contemporary modernist developments, however large or “advanced” like the apple, facebook, google, masdar mega-compounds are, without exception, of a suburban nature, horizontal or vertical mono-thematic sprawl –in general, regarding the latest talk about “smart cities”, incorporating the ever evolving newest technologies of connectivity, it should not be confused what is just a matter of infrastructure with urban fabric form and town planning.

We are the first generation to have reacted against the cataclysmic modernist devastation of the world by building an operative critique backed by a general theory for a human-scale architecture and urbanism. This model of new traditional architecture and urbanism is being applied worldwide. I had the lucky misfortune to grow up in cities which had been spared the war-destructions, yet already suffered the tragic consequences of modernist redevelopment policies. As i grew up i witnessed how the traditional European city was being deconstructed as social, physical economic structure, as an ethical and aesthetic space. It is that model which is common to all European nations. It had allowed the open mixed modern society to emerge and flourish. It is that city model, inherited from Athens and Rome, which modern societies worldwide desire, but are everywhere admonished by modernist propaganda, that they can no longer have, except for holidays and entertainment.

We would like to focus now on a specific Identity Building process: Rejection. It is based on the notion of non-identification with the characteristics -formal, conceptual, emotional- of something, leading to its rejection. Throughout your career, you have had a clear stance regarding your own notion of how to make Architecture. How do you relate to the process of Rejection in your take on other approaches towards architecture? For instance, Modernism, Futurism or High-Tech architecture? Do you completely reject them or do you see relevance in some of their characteristics, within their context?

Modern traditional architecture and urbanism are not motivated by a feeling of rejection but by the urgency of reconstruction. Reconstruction because modernism has deconstructed architecture and urbanism physically and mentally. I am about to publish the 9th volume of Le Corbusier’s oeuvre complete called “Le Corbusier after Le Corbusier- LC translated, corrected, completed” proving that if there is a quality in his work, that quality can be achieved by traditional architectural means, techniques, materials, construction processes. The interesting forms of architectural modernism, futurism, high-tech, were without exception, pioneered by industrial production, storage and transportation building design, by driving and flying vehicles design, by machine, weapons and tool design. They are characterized by an aesthetic which is not place-bound, but purpose- and function-bound. The forms of oil-rigs, the monumentality of grain stores, the beauty of cooling towers and the aerodynamic elegance of an aeroplanes don’t deliver the typological or formal repertoire to the making of human scale places, buildings or cities.

What is commonly called high- tech is uniquely related to fossil-fuel energies and its synthetic materials. I am suggesting that architects and planners become primordially concerned not with the “historicity” of traditional architecture and urbanism, but with their technology, with the techniques of building settlements in a specific geographic location and condition and hence with local architectural and urban cultures.

The other common belief is that progress, human progress, is necessarily linked to high-technological progress. Technology is the logos of technique. Technology is neither “high” nor “low.” What superficially looks like “high” may be “low” in ecological terms. I advocate to respect, study and use traditional ideas where and when they are relevant for us the living, essential for our well-being. They are repositories not merely of humanity, but of humaneness and ecology.

New urbanism and modern traditional architecture are to this day the only coherent theory of environmental design based on extremely long-term sustainability, founded on millennial experience. The many architects who practice it, do so despite their architectural education and generally against overwhelming academic prejudice but sustained by wide public support and market demand.

Mr Krier is a world-renowned architect, urban planner and architectural theorist pioneer in promoting the technological, ecological and social rationality and modernity of traditional urbanism and architecture; he is considered the “Godfather” of the “New Urbanism” movement. Following a stint at the University of Stuttgart, he started his career in 1968 working with James Stirling and serving as a professor at the Architectural Association and the Royal College of Arts in London. Since then he has combined with his writings and teaching an international architecture & urban planning practice, which include projects in Mexico, Guatemala, USA, England, France, Germany, Holland, Belgium, Romania, Cyprus, Italy and Spain. As a professor he has taught at Princeton University, the University of Virginia, Yale University, and has guest lectured at numerous institutions.

Starting from 1987, Mr Krier is H. R. H. the Prince of Wales’ advisor, and responsible for the master-planning and architectural coordination of Poundbury, the Duchy of Cornwall’s urban development in Dorset, U.K. and , since 2003 the Cayala development in Guatemala with Estudio Urbano. In addition, he has worked as industrial designer for Giorgetti since 1990.

Among his numerous publications deserves special mention “The Architecture of Community-2009.” a summary of his theories and practice.