Editorial

CARTHA

On the night of the 29 December 1940, London was hit by one of the heaviest bombings during The Blitz1 destroying most of the buildings around the Paternoster Row, curiously leaving the neighbouring St. Paul’s Cathedral intact. From 1961 to 1967 the Corporation of London, partially inspired on a proposal by Sir William Holford, redeveloped […]

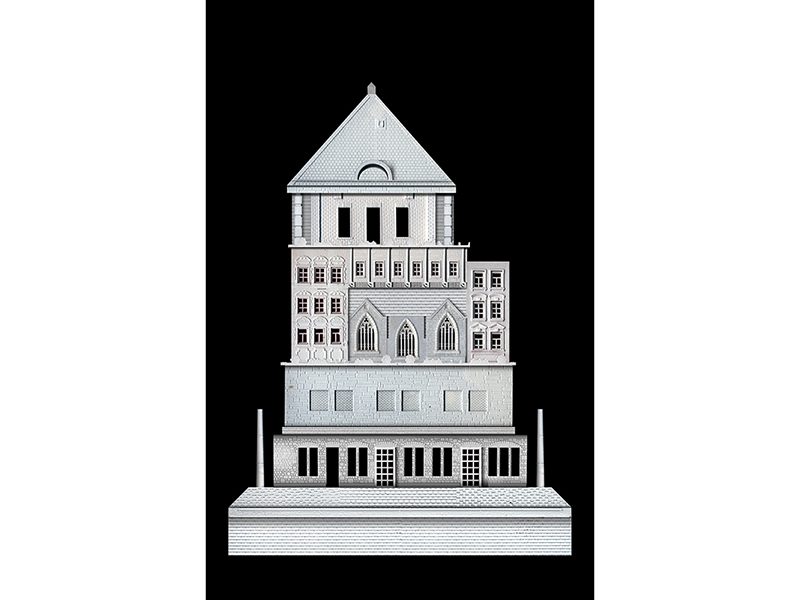

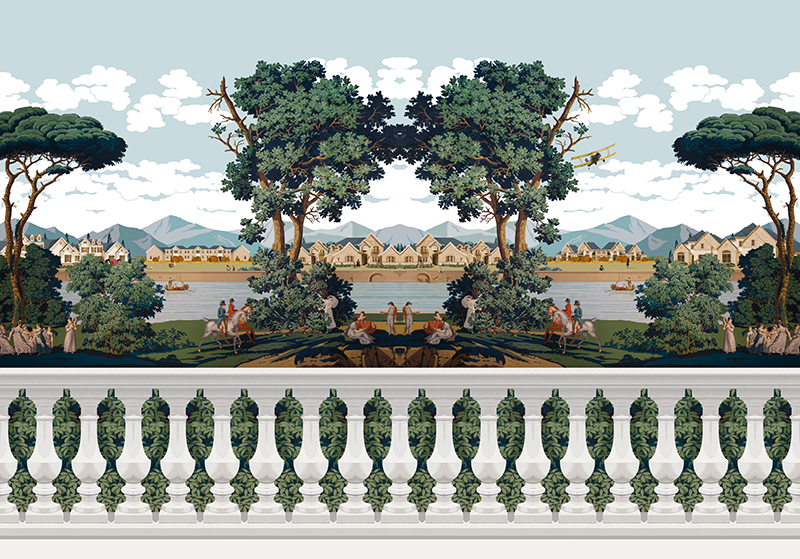

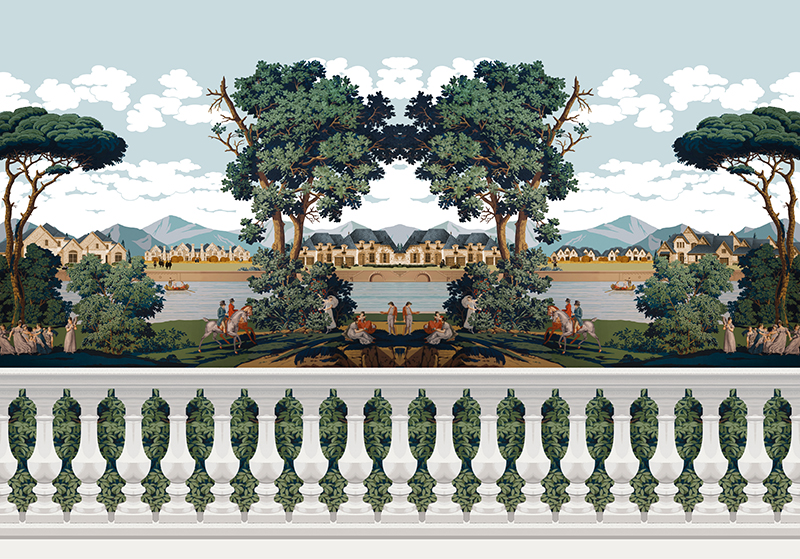

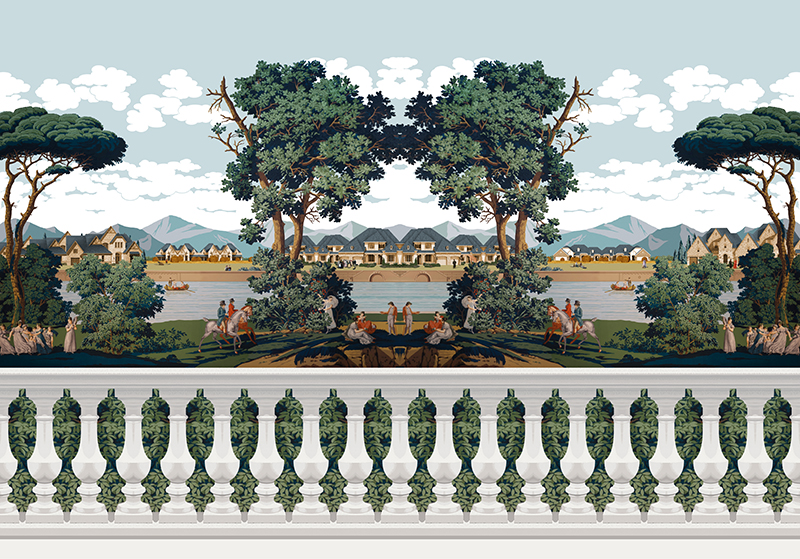

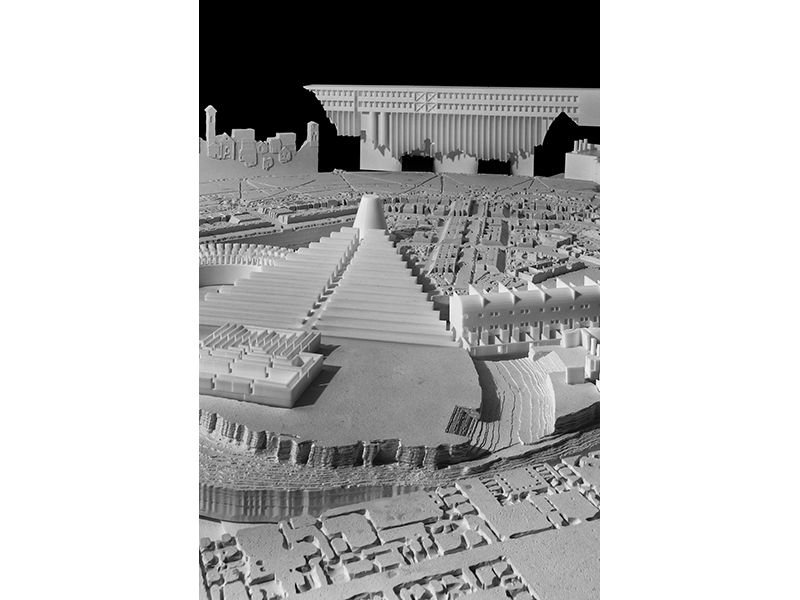

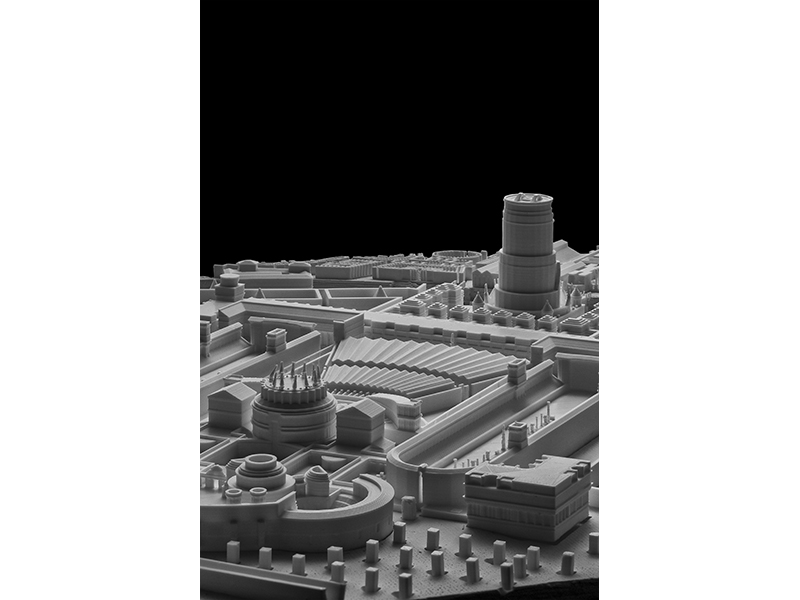

On the night of the 29 December 1940, London was hit by one of the heaviest bombings during The Blitz1 destroying most of the buildings around the Paternoster Row, curiously leaving the neighbouring St. Paul’s Cathedral intact. From 1961 to 1967 the Corporation of London, partially inspired on a proposal by Sir William Holford, redeveloped the destroyed area with a project that ended up being both unsuccessful and controversial due its highly contested modern architecture2 and a very low occupancy rate. This led to a point when, only 20 years after its completion, a new competition to redevelop the area was organised, resulting in a winning proposal by Arup. Then, in 1990, the result of the competition was dismissed in favour of a plan by architect John Simpson championed by HRH Prince of Wales. This plan however was perceived as a “Pastiche”3 and was never executed due to the 1993 recession. Finally in 1996 a master plan by Sir William Whitfield was selected and successfully developed up until its conclusion in 2003.

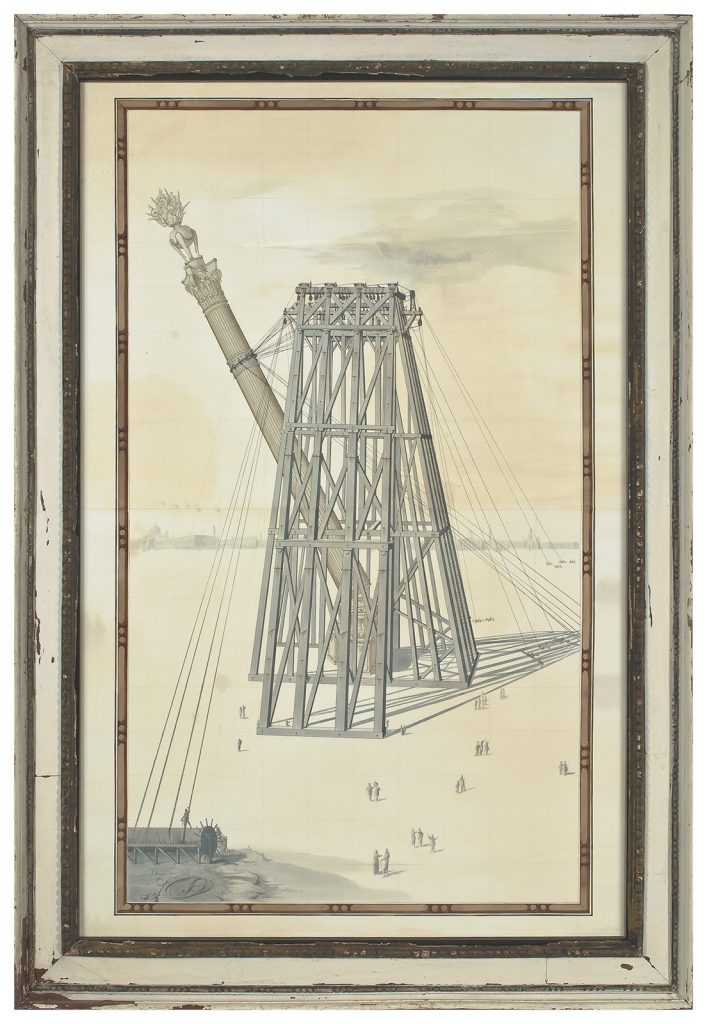

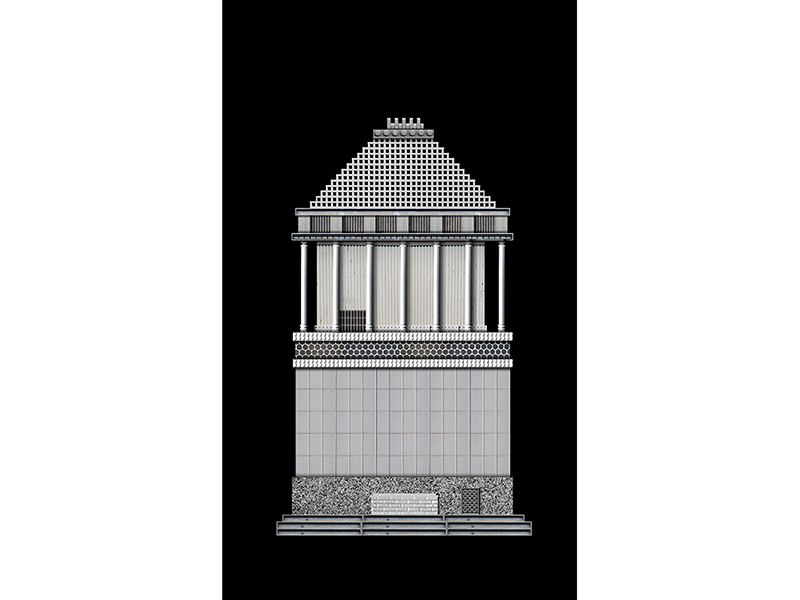

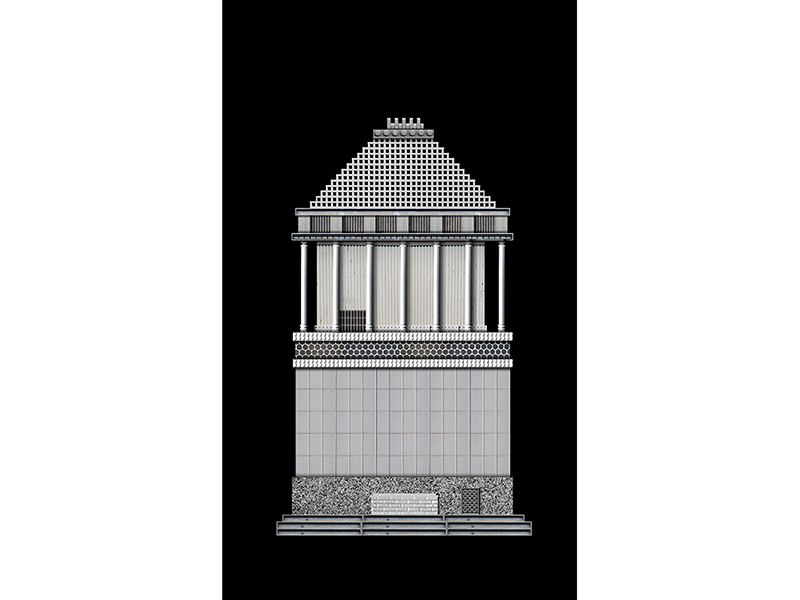

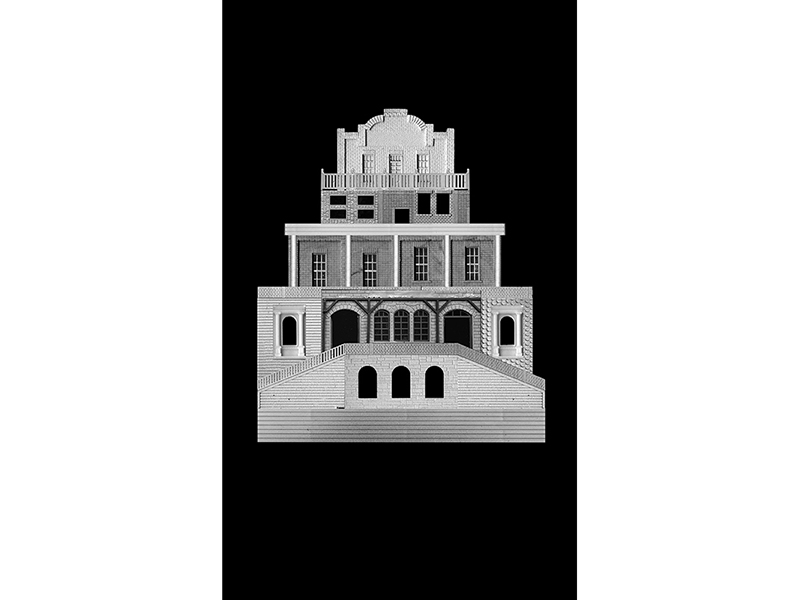

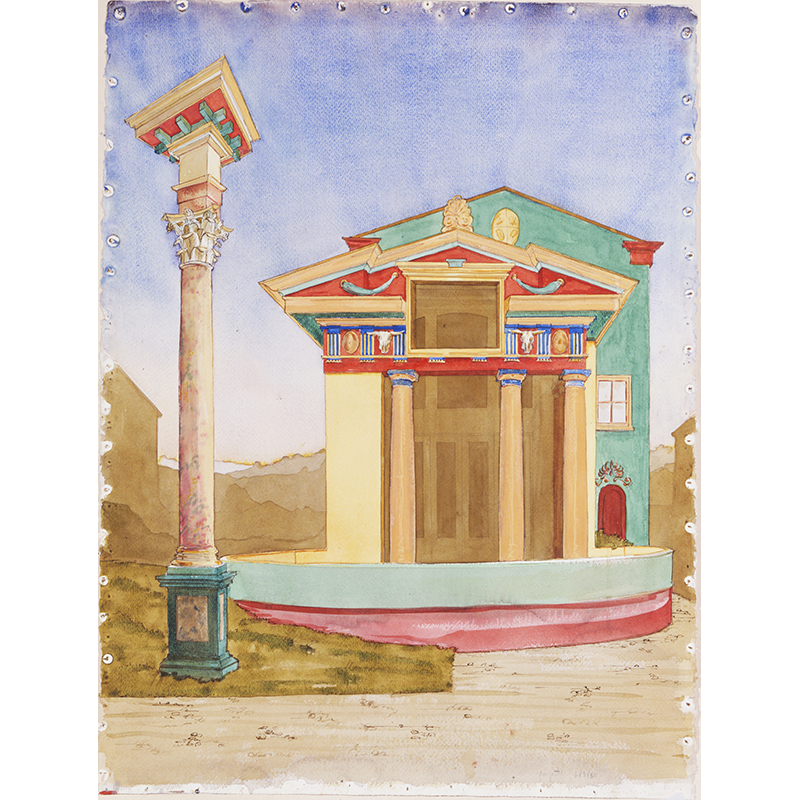

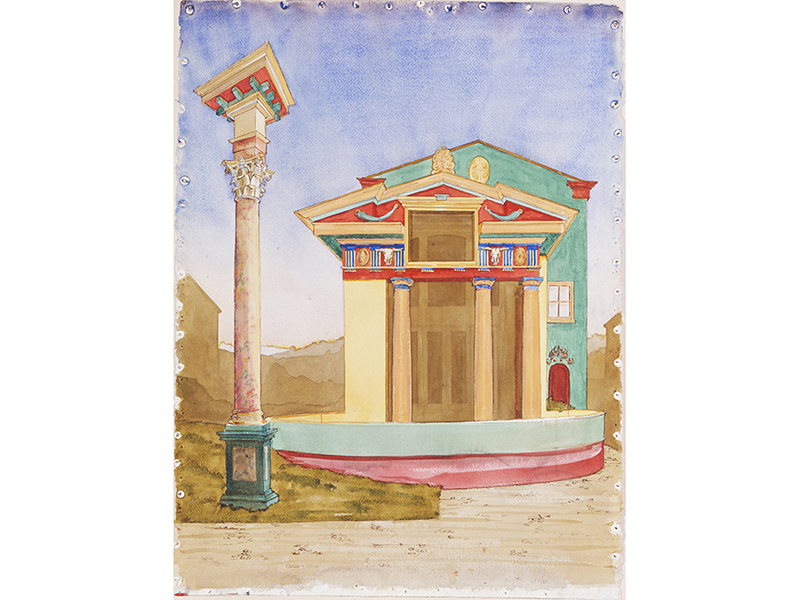

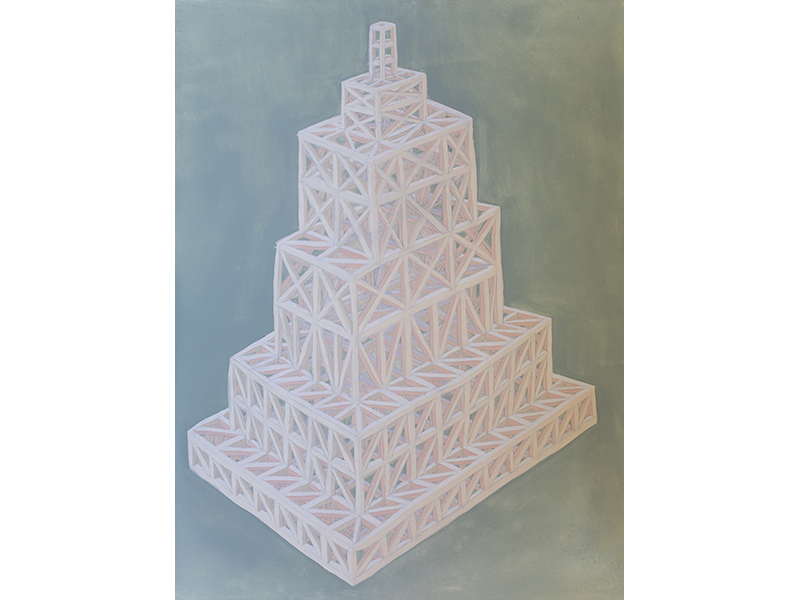

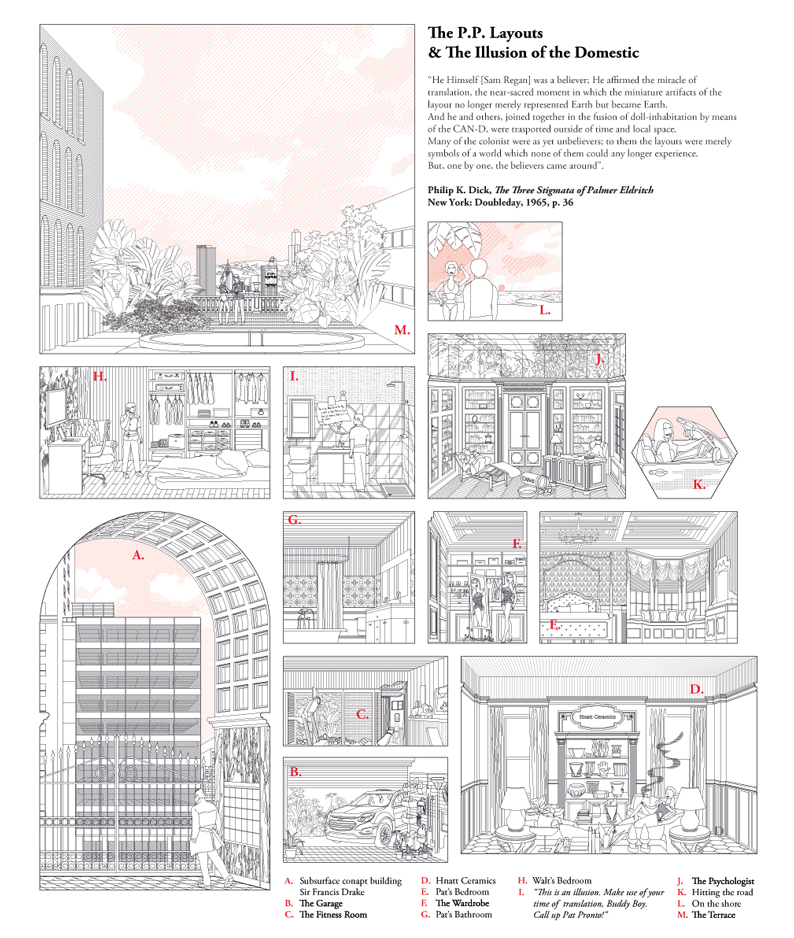

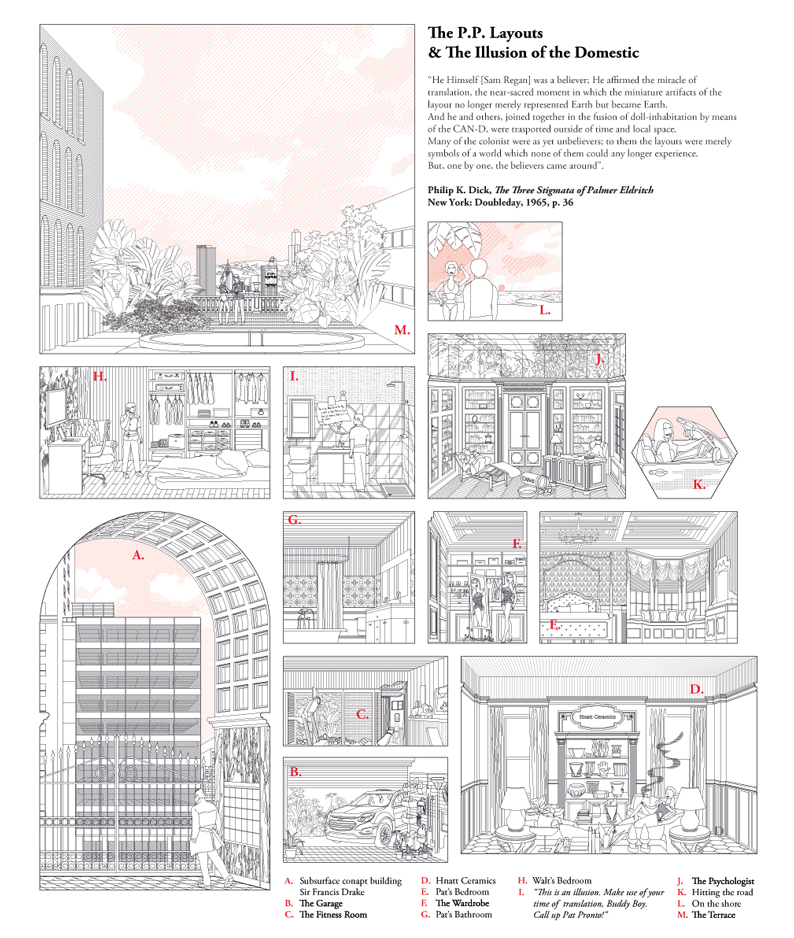

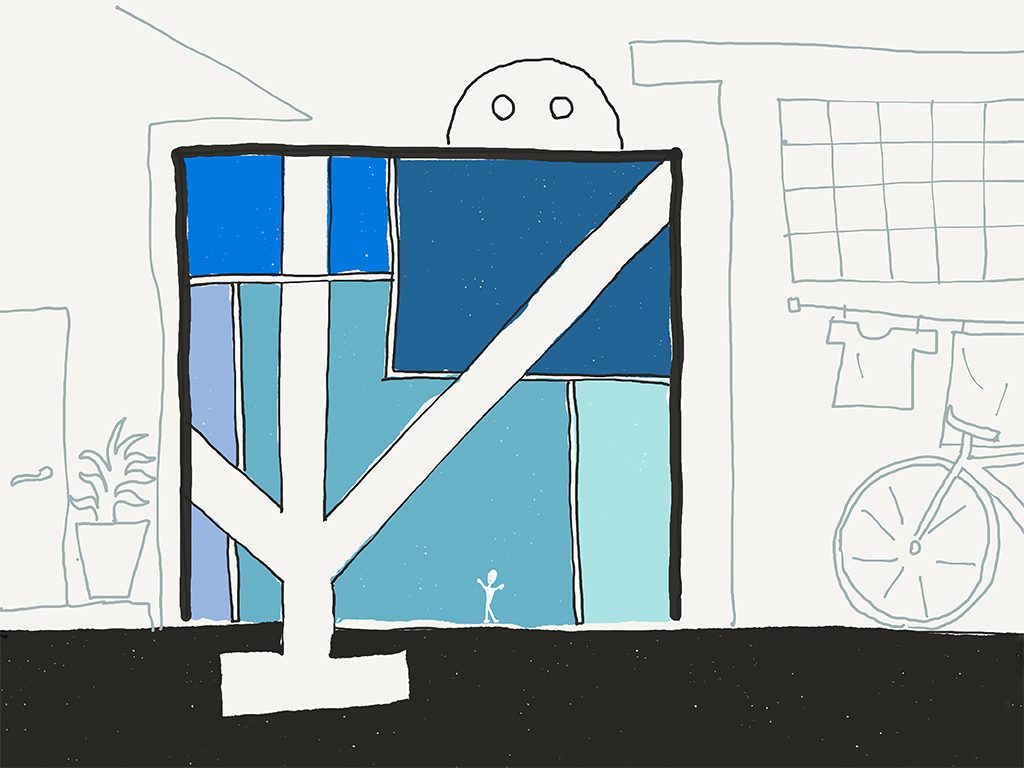

The development, currently owned by The Mitsubishi Estate Co.4, consists of a large central square inserted in the urban fabric, with small roads cutting through the blocks around it. At the center of the square, a Portland stone corinthian column of 23 meters high stands as the main monument of the area. Clearly inspired by Christopher Wren’s Monument to the Big Fire and Inigo Jones’ west portico of the old St. Paul’s cathedral, the column designed by Whitfield, functions not only as a symbol of the square but also as a ventilation shaft for a service road under it. Half monument half technical facility, private while seeming public, corinthian but built in the early 2000s, real and fake. The column embodies a series of contradictions and accidents that surpass by far its mere physical presence and historical context, mimicking the common imaginary of what monuments should look like while performing a technical function for a public infrastructure.

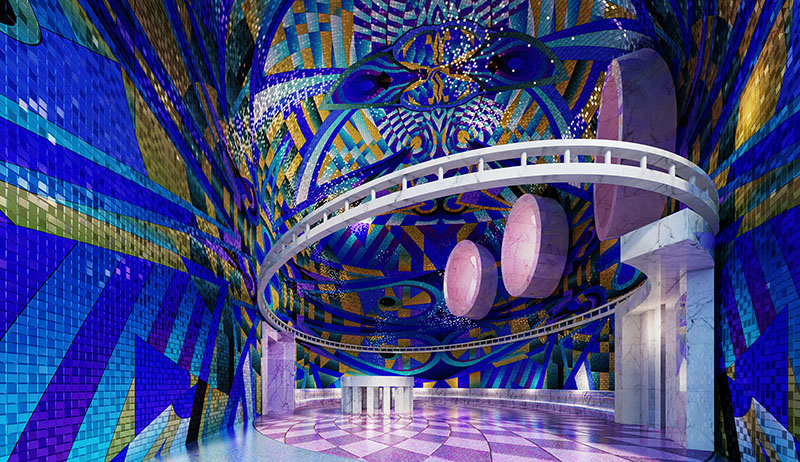

The Paternoster column is definitely not the only built structure that embodies Fiction in several of its layers, but it proved to be of great help when asking ourselves where the limits between Fiction and Reality stand in built or unbuilt Architecture. In the same logic, we decided to take the case study as research and communication tool for the whole cycle. It allowed us to assure a certain degree of coherence and relatability in the outcome of both issues, while presenting a stable basis for possible further development. This relatability is in turn reinforced by the ambivalence / complementarity in the choice of format for the two issues which suggests yet another possible line of research related to the influence of the medium in current representations of Fiction and Reality.

The 29 case studies in this cycle, 12 in text and 17 in image, set Fiction free from preconceived ethical or political judgements and place it under an uncompromised light. They offer valuable, critical insights from multiple perspectives, reflecting on the question launched in our calls while expanding on it in rich and refreshing ways, drawing from the current context and relating it to historical references, to multidisciplinary traces and to fictional realms. They attempt to find the slightest possibility of a steady path up the slippery slope of the research on the Limits of Fiction in Architecture.