II

THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CITY.

A PALIMPSEST .

Guest editors: Victoria Easton, Matilde Cassani, Noura Al Sayeh

Guest editors: Victoria Easton, Matilde Cassani, Noura Al Sayeh

CARTHA

Continuing with the year-long reflection on The Form of Form, Issue II invites you to analyse the current form of the city with The Architecture of the City. A Palimpsest, guest edited by Victoria Easton, Matilde Cassani and Noura Al Sayeh The issue’s conception coincides with the exhibition The books of the Architecture of the […]

Continuing with the year-long reflection on The Form of Form, Issue II invites you to analyse the current form of the city with The Architecture of the City. A Palimpsest, guest edited by Victoria Easton, Matilde Cassani and Noura Al Sayeh

The issue’s conception coincides with the exhibition The books of the Architecture of the City, curated by Victoria Easton, Guido Tesio and Kersten Geers, at the Istituto Svizzero in Milan, celebrating the 50th anniversary of Rossi’s seminal book.

While the previous issue, How to Learn Better, guest edited by Bureau A, discussed the conception of form through the questioning of pedagogical approaches in architecture, this second issue, focuses on the form of the city itself through the lens of a palimpsest of Aldo Rossi’s pivotal oeuvre.

Revisiting The Architecture of the City seemed a necessary exercise in a moment where drastic changes in the way we read and form the city make it necessary to question the current state of architecture in the same way that Rossi questioned the modernist doctrine back in 1966.

This palimpsest proved that the ideas embodied through the 33 chapters are as valid and lucid as they were 50 years ago. Their flexibility and, at times, ambiguity provided a fertile soil for reflections that not only seem pertinent but also urgently necessitated by the contemporary city, which becomes more and more abstract yet complex with the passing of time and the ever-changing nature of society.

Reflecting on form through the revisiting of Rossi’s oeuvre enriches our cycle on The Form of Form, suggesting another way in which form and Architecture relate, while pointing to our final issue of the cycle, where we will confront form, city and architecture from yet another parallel perspective.

Victoria Easton, Noura Al Sayeh, Matilde Cassani

«Tout est forme, et la vie même est une forme.» Honoré de Balzac. By teaching a child how to put little wooden shapes into correspondingly shaped holes, one could consider form as something that is absolutely defined. However the transitive of this title in itself suggests the malleability of form, of which the phenomenon of […]

«Tout est forme, et la vie même est une forme.»

Honoré de Balzac.

By teaching a child how to put little wooden shapes into correspondingly shaped holes, one could consider form as something that is absolutely defined. However the transitive of this title in itself suggests the malleability of form, of which the phenomenon of the city offers one of the best examples.

The city is shape. The city is shaping shapes. But the city is also about rules and the defining of rules. Enough has been written on the topic of the city and our ambition here lies not in reassessing this topic in a completely new way. On the contrary, we consider one book to still be relevant as one of the best commentaries on the city and its cosmos. Exactly 50 years ago Aldo Rossi wrote his seminal work The Architecture of the City and suggested in the most dedicated, vague and yet convincing manner the ways in which the city is defined by shape. With his legendary ambiguity, Rossi believed in the permanence of form but also in its obsoleteness.

We choose to dedicate this issue of CARTHA to the city, and to its architecture. Paying tribute to Rossi, we have borrowed the original structure from The Architecture of the City as a canvas, with the ambition of attempting to delineate their possible contemporary interpretation. Each author was attributed one of the 33 subtitles of the original book, and was given carte blanche to define the extent to which his or her contribution would directly relate to Rossi and to the topic assigned. The resulting contributions range from essays and critiques to project descriptions and images. The initial motivation was that the result would be as eclectic and fragmented as its source, while also emphasising the contemporaneity and universality of Rossi’s thoughts. Above all, this issue of CARTHA has the aspiration to represent a collective work, one that honours the collective form of form: the city.

Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli

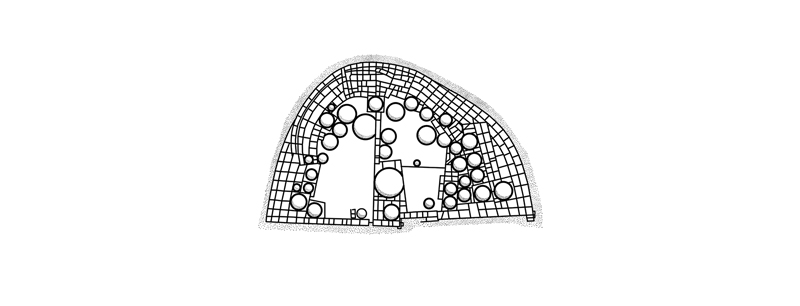

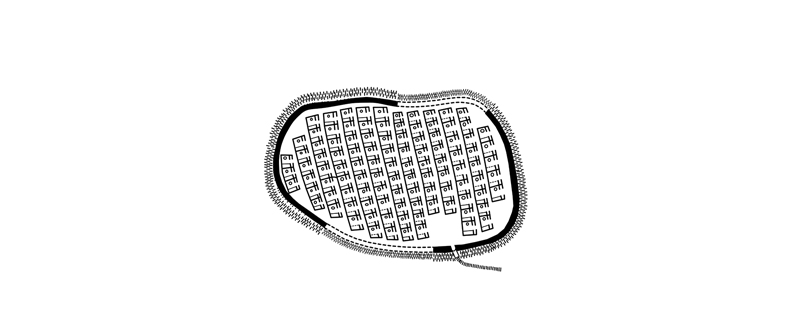

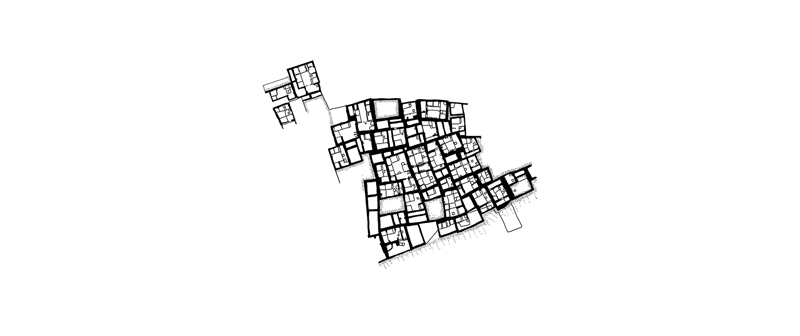

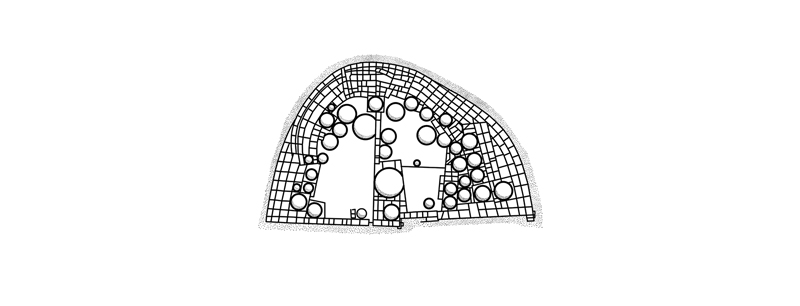

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS The Individuality of Urban Artifacts Three maps of three paradigmatic proto-cities are presented. The black and white plan drawings are stripped of information in order to highlight the bare form of the cities. As apparently abstract as they are, these documents immediately reveal forms that at this […]

Three maps of three paradigmatic proto-cities are presented. The black and white plan drawings are stripped of information in order to highlight the bare form of the cities. As apparently abstract as they are, these documents immediately reveal forms that at this stage in history are capable of absorbing and communicating a large set of values connected to the construction of the city and its social organization.

The town of Çatalhöyük, today located in Turkey, the pueblos of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, and Biskupin in Poland, are three settlements belonging to three different times in history. While differing in their general urban planimetry, the three ancient cities bear several common traits that make them comparable.

First of all, the form of each of these primordial cities is instantly recognisable; second, the urban form is obtained from the continuous agglomeration of a basic, individual artefact: the single cell. This space hosts the bare functions of living, those we could call “domestic”, but it also embodies social meaning and ritual purpose; in Çatalhöyük, bodies were buried under the floors and the walls were painted with vivid, sacred images.

Only in the case of Chaco Canyon are the cells, called the “pit houses”, coupled with larger rooms, called “kivas”, which apparently hosted collective spaces. Even when these variations are introduced, the assembling rules that govern the whole urban system are repetitive and those that generate architecture are strictly interdependent with the ones generating the city.

In these proto-cities, architecture does not seem to “express only one aspect of a complex reality”, but is still able, at this age in history, to directly embody specific material needs and a clear social structure.

The social organisation lying behind the form of the three settlements appears, in fact, to be one based upon a community of equals, where everyone, regardless of gender or age, occupies the same social and physical space. The absence of a class structure implies an absence of formal representation of class differences: the construction of the material and spatial structures constituting the single architectures (walls, roofs, rooms), and the urban artefact as a whole, is in direct response to pure necessity.

The form of the city appears then as the result of a purely quantitative addition of domestic modules adapted only to topography and with the added value, especially in the case of Biskupin, of producing a defensive layer.

At this primordial stage, architecture has no individuality and, is one thing with the urban form. In the case of Çatalhöyük, the relationship is even more extreme as the roofs of the houses are used for communal activities, as well as serving as the only connecting infrastructure of the houses. One might say that the house absorbs all urban functions, material, and representative, and contains the rules to form (the form of) the city.

At the dawn of civilization and many ages before functionalism came to be an ideological setting for the construction of architecture and the city, even the most basic distinction of functions associated with specific spaces does not yet exist. The cell is the barest form of what will be the “house”, but is already something different from the primitive hut: it does not only protect from weather conditions and outside dangers, but settles the rules for sharing a territory, provides a collective meaning, and structures the form of the city.

Ala Younis

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS The Urban Artifact as a Work of Art In his first visit to Baghdad in 1957, Le Corbusier asked Iraq’s Director of Physical Education: “A swimming pool with waves?” Enthusiasm over a pool with artificial waves was stoked by their mutual interest in aqua sports. What Le […]

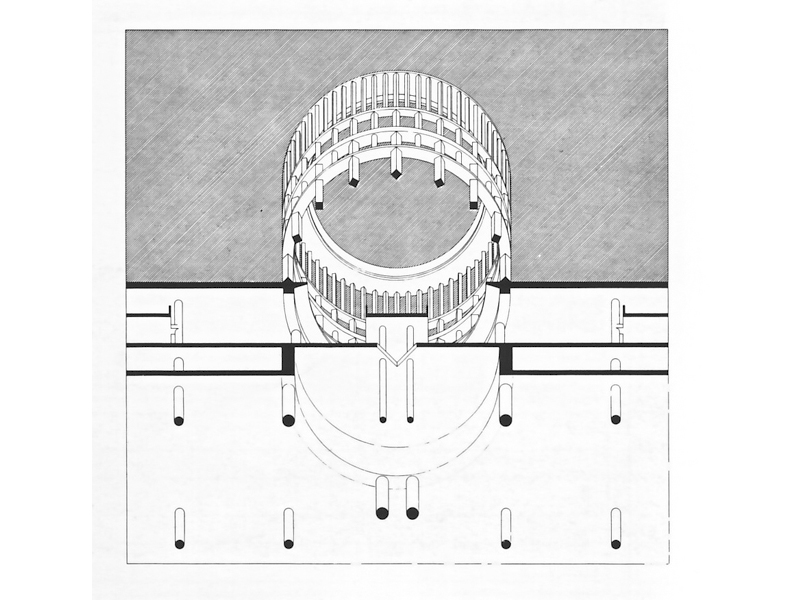

In his first visit to Baghdad in 1957, Le Corbusier asked Iraq’s Director of Physical Education: “A swimming pool with waves?” Enthusiasm over a pool with artificial waves was stoked by their mutual interest in aqua sports. What Le Corbusier and the Iraqis wanted for the Sport Center was a structure that would embody a modern Mesopotamia whose architecture would feature waters channelled from the Tigris, and an artificial wave pool collected from its flow. From now on, planning Baghdad becomes a strategy, an expression of power, or a necessity when it takes the form of enabling a future possibility.

In 1959, the Ministry of Public Works and Housing asked Le Corbusier: “What do you think about the creation of a second stadium in Baghdad?” He answered: “In principle it appears to me to be quite useless as it minimizes the one or the other by a sterile competition between them.” (1) Le Corbusier’s Saddam Hussein Gymnasium metamorphosed through numerous iterations of plans over a period of twenty-five years before it was finally inaugurated in 1980. Up until then, the commission passed through five military coups; six heads of state; four master plans, each with its own town planner; a Development Board that became a Ministry and then a State Commission; a modern starchitect among a constellation of many others with their associated architects, draftsmen, contractors, translators and lawyers; local architects accompanied by similar structures from their own consulting firms, from government departments and parallel commissions; more than one local artist/sculptor; eager competitors; and other monuments that appeared and disappeared as a result of these same conglomerations.

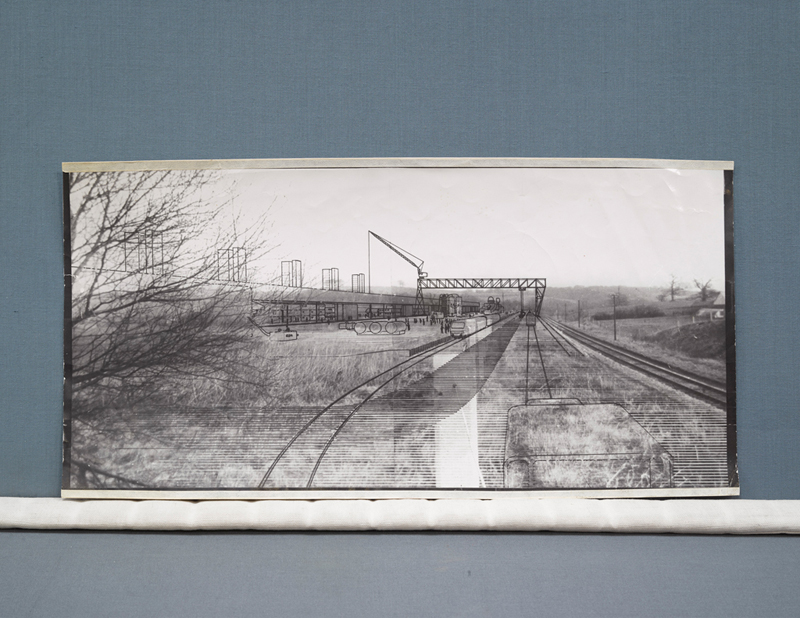

The Baghdad-based consulting firm Iraq Consult (1952–1978), led by its founder Rifat Chadirji (1926– ), facilitated the continuously interrupted process of building the gymnasium. In addition to his involvement in other aspects of the project, Chadirji took a set of 35mm photographs of the Gymnasium in 1982. These photographs and other documents of the urban artefacts he built exist now in the form of montages made up of scraps smuggled in and out of Abu Ghraib prison while Chadirji served part of a life sentence. The architect produced these compilations as he edited his notes into a massive monograph that renders the development of his architectural philosophy within the context of the modernity-identity discourse and his local and international commissions, and how these were affected by political conflict.

In December 2011, I asked the exiled architect about the parallel fates of the Gymnasium and its creators. From his response, it seemed to me that he revisited the enthusiasm that had driven the international architectural endeavours. At 85, he considered his work in introducing samples of international modernism was only for these projects to be experienced first-hand by the students and citizens of Baghdad. In another expression of dismay, he said that his buildings are being demolished one after another.

Chadirji’s first statement illustrated an interesting image of power relations in architecutre; to outsource architects to present structures on a platform for local viewers, removes any attributed or attempted locality and reduces the buildings to their basic relationship with their makers. The urban artefacts, in this image, become basic forms that aggregate, propagate, and negate forms of other structures. Perhaps this power relation is what Le Corbusier tried to explain when he responded to the question regarding a second stadium, or the fates Chadirji was refusing in his second statement.

Le Corbusier created an image of such power relations in his model of the superstructures for his Cité radieuse in Marseille. On an inclined platform, he presented multiple architectural forms existing next to each other, the background was an image, and there were no other structures around nor beneath this presentation. Whether serving the residents of the main structure beneath (the building) or the city, in the images produced by Le Corbusier’s model and Chadirji statement, the buildings are meant to come to the foreground, emptied of all players. Between these forms and a sweeping landscape, two spaces remain: one of pure air permeating between the buildings, and an overall one containing space that surrounds the block of forms interchanging their power, in a secluded universe where nothing else exists.

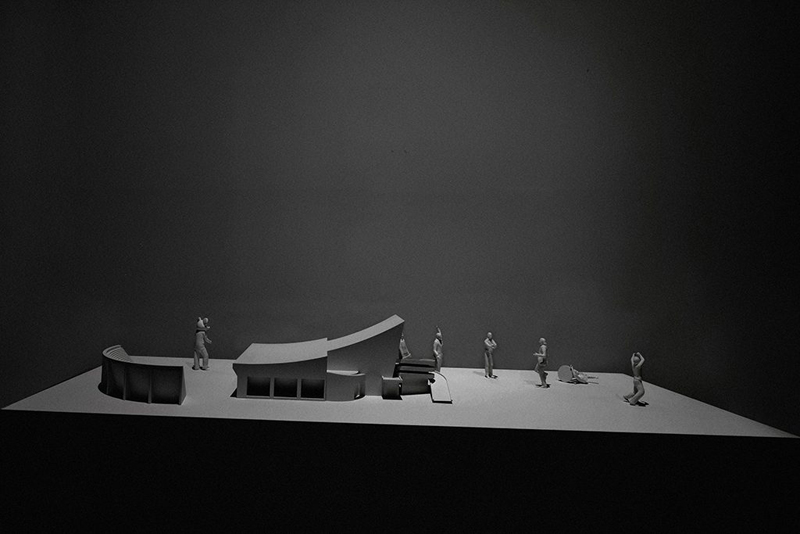

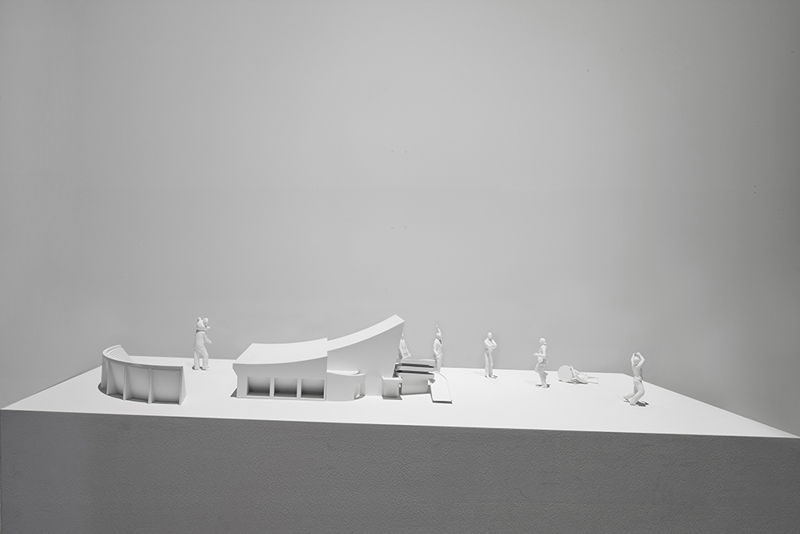

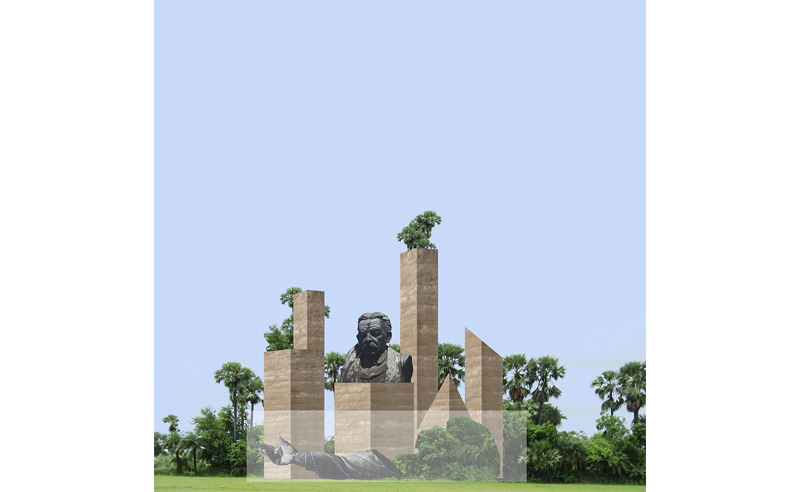

“Plan for Greater Baghdad” is a project heavily based on archives, found images, and objects, that reproduce the story and politics around the Saddam Hussein Gymnasium project in the form of a timeline, an architectural model and a set of characters. The characters reproduce citations of imageless gestures that relate to performances of design, power, and designing power. They are retrieved as a set of motions and signals enacted by characters frozen in the denouements of historical time: Chadirji jogging in the courtyard of Abu Ghraib Prison or hurrying to photograph his monument before it is demolished; a young Saddam Hussein on the edges of the scene as monuments’ (de)constructor; and Le Corbusier raising his arm to gesture a backstroke of an artificial wave in a swimming pool to pull its waters from the Tigris. On an inclined base, an architectural model of the gymnasium is fixed next to, but different in proportion from, the set of characters. The set up aimed to looks at monuments, their architects, for governments, through the alternating power relations between them in the times of shifting states. In the diverse iterations of the project, these elements morph as they migrate within a universe of possible artistic and architectural intentions.

1 Report by Director General, Technical Section 2, Baghdad, titled “Baghdad Stadium, Notes: From Mr. Le Corbusier, Architect”, 4 May 1959.

Nelson Mota

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS Typological Questions This interview never happened. The answers provided by Aldo Rossi were all collected from the section “Typological Questions” in the first American edition of his The Architecture of the City, published in 1982. The answers given by Christopher Alexander were gathered from the chapter “The […]

This interview never happened. The answers provided by Aldo Rossi were all collected from the section “Typological Questions” in the first American edition of his The Architecture of the City, published in 1982. The answers given by Christopher Alexander were gathered from the chapter “The Timeless Way” in his The Timeless Way of Building, published in 1979. In both cases the original spelling was preserved.

Nelson Mota (NM): The reason for bringing you two together is your common interest in time and temporality as key factors in the rapport between nature and urban artifacts. Aldo calls it the creation of an “artificial homeland” and Christopher names it “the timeless way of building”. How far back should we look in order to make sense of this relationship?

Aldo Rossi (AR): The “artificial homeland” is as old as man. Bronze Age men adapted the landscape to social needs by constructing artificial islands of brick, by digging wells, drainage canals, and watercourses. […] Neolithic villages already offered the first transformations of the world according to man’s needs.

Christopher Alexander (CA): [The timeless way of building] is thousands of years old, and the same today as it has always been. The great traditional buildings of the past, the villages and tents and temples in which man feels at home, have always been made by people who were very close to the center of this way.

NM: Both of you describe the act of building as being fundamentally a social practice. Does this mean though that building practices are particular to a specific time and place?

AR: The first forms and types of habitation, as well as temples and more complex buildings, were […] developed according to both needs and aspirations to beauty; a particular type was associated with a form and a way of life, although its specific shape varied widely from society to society. […] I would define the concept of type as something that is permanent and complex, a logical principle that is prior to form and that constitutes it.

CA: At the core of all successful acts of building and at the core of all successful processes of growth, even though there are a million different versions of these acts and processes, there is one fundamental invariant feature, which is responsible for their success. Although this way has taken on a thousand different forms at different times, in different places, still, there is an unavoidable, invariant core to all of them.

NM: You both highlighted permanence or invariance as a key feature in successful acts of building. Can these acts still be copied or replicated in this day and age?

CA: There is a definable sequence of activities which are at the heart of all acts of building, and it is possible to specify, precisely, under what conditions these activities will generate a building which is alive. All this can be made so explicit that anyone can do it.

NM: Could you clarify what that sequence of activities is, Christopher? Have you discovered a sort of formula that everybody can use to create great buildings?

CA: This one way of building has always existed. […] In an unconscious form, this way has been behind almost all ways of building for thousands of years. […] But it has become possible to identify it, only now, by going to a level of analysis which is deep enough to show what is invariant in all the different versions of this way.

NM: Aldo, do you agree with Christopher on the idea that there is a sort of inherent rule that performs as a structuring principle of architecture and that we should be able to identify?

AR: In fact, it can be said that this principle is a constant. Such an argument presupposes that the architectural artifact is conceived as a structure and that this structure is revealed and can be recognized in the artifact itself. As a constant, this principle, which we can call the typical element, or simply the type, is to be found in all architectural artifacts. It is also then a cultural element and as such can be investigated in different architectural artifacts; typology becomes in this way the analytical moment of architecture, and it becomes readily identifiable at the level of urban artifacts.

NM: Does this mean that we can glean information on how to build a housing complex today from, for example, a Roman insula?

AR: I tend to believe that housing types have not changed from antiquity up to today, but this is not to say that the actual way of living has not changed, nor that new ways of living are not always possible. The house with a loggia is an old scheme; a corridor that gives access to rooms is necessary in plan and present in any number of urban houses. But there are a great many variations on this theme among individual houses at different times.

CA: The power to make buildings beautiful lies in each of us already. It is a core so simple, and so deep, that we are born with it.

NM: Do you mean that metaphorically?

CA: This is no metaphor. I mean it literally. Imagine the greatest possible beauty and harmony in the world – the most beautiful place that you have ever seen or dreamt of. You have the power to create it, at this very moment, just as you are.

NM: Could you clarify that? How do I have that power? How do architects have that power? What do we need to activate it?

CA: To become free of all these artificial images of order which distort the nature that is in us, we must first learn a discipline which teaches us the true relationship between ourselves and our surroundings. Then, once this discipline has done its work, and pricked the bubbles of illusion which we cling to now, we will be ready to give up the discipline, and act as nature does. This is the timeless way of building: learning the discipline – and shedding it.

NM: Aldo, do you think that typological studies can help us in “pricking the bubbles of illusion”, as Christopher puts it, which are created by dogmatic architectural systems, codes, or methods?

AR: Ultimately, we can say that type is the very idea of architecture, that which is closest to its essence. In spite of changes, it has always imposed itself on the “feelings and reason” as the principle of architecture and of the city. […] Typology is an element that plays its own role in constituting form; it is a constant. The problem is to discern the modalities within which it operates and, moreover, its effective value.

Ahmad Makia

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS Critique of Naive Functionalism In the fall of last year, Eric Yearwood, a stand-up comedian and actor, was asked to perform for a film project. The plot goes something like this: Eric pretends to be asleep at a New York subway platform. He is carrying a phone. […]

In the fall of last year, Eric Yearwood, a stand-up comedian and actor, was asked to perform for a film project. The plot goes something like this: Eric pretends to be asleep at a New York subway platform. He is carrying a phone. As he is asleep, a rat will crawl onto him. It will then access his phone, launch the camera option and then click the photo icon to capture a self-portrait. Later, Eric will leap up and act surprised.

Zardulu, the scriptwriter and producer, will be filming this entire event and the main goal of the project is to create ‘viral content’ when the film is later uploaded to the Internet. Eric grows curious about the project, but wonders where the rat will come from. In an interview with Gimlet Media, Eric described Zardulu’s studio as a place where rats “would run [around a] maze[…], leap over little obstacles … there was … a little pool that they would swim across to retrieve certain things. And she had them trained in a way that was pretty amazing.” (1) For Eric’s video, they smear the ‘Home’ button with peanut butter, tricking one of Zardulu’s rats into taking a picture. Eric then learns that this job is part of Zardulu’s extensive body of work comprised of coordinated illusions and absurdities across New York City. More than simply relying on physical witnesses, some of Zardulu’s works include editorials designed for the clickbait industry. In Eric’s testimony, he explains how her studio is filled with creations, such as a suit of human hair, made specifically for spreading fantastical tales across the world.

Eric accepted the opportunity without much hesitation. (He was compensated for his efforts, too.) A few days after the shooting, Zardulu submits the video to Connecticut TV posing as Don Richards. The video goes viral and today is commemorated as the magical phenomenon of ‘Selfie Rat’. Soon after, different media platforms pick up the story and comments begin to pour in as analysts, eye-witnesses and professional de-bunkers alike, all have their say. This coupled with the older news of ‘Pizza Rat’, where a rat is filmed transporting a slice of pizza through New York’s subway system, created a very small trend in our contemporary media where rats were portrayed as extra-terrestrial, hyper urbanized creatures.

Suddenly, a member of the public identifies Eric in the video as an actor and the hoax is exposed on the Internet. Also Pizza Rat’s authenticity comes into question as another possible video manipulation and suddenly a discourse emerges about what is real and what is not. Eric promised to keep anonymity regarding this project, but after the hoax scandal he spoke out for Zardulu. Zardulu did the same by establishing a Twitter and Facebook account. Here she described herself as a performance artist whose purpose is to reinvent the lost and undervalued practices of mythmaking. Both performers made possible the idea that many absurd things seen in New York’s subway system could be Zardulu’s hoaxes that perform along with the daily rhythms of the city. A few weeks later, another person reports two rats coordinating the transfer of a slice of pita bread up the subway stairs. Only if you spiral down the illusionary world of Zardulu can you begin to understand how effective it is. The emerging narrative is a small hysteria spreading across the world where people are negotiating the possibility that rats and their operations were coordinated by a mythic figure in a place like New York City. Achieving this in the age of algorithms is a success.

This exercise reveals our need — or thirst — for other worlds and other stories. Yet its main achievement is providing access to the possibility of other worlds. The terrain and ground being used in Zardulu’s work is the city, where its matter and inhabitants are not only used as illustrations for our rationality, logic, lineage, structure, grids, history, memories, inheritances and values. Here the city is generated as a force field of combustive and imaginative processes.

1 See podcast transcript.

José Pedro Cortes

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS Problems of Classification José Pedro Cortes (Porto, Portugal, 1976) studied at Kent Institute of Art and Design (Master of Arts in Photography) in the UK. He has been exhibiting regularly during the last ten years and has published four books. He is also the founder and co-editor […]

Alejandro Valdivieso

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS The Complexity of Urban Artifacts Rafael Moneo (born in Tudela, Navarra, 1937) has lived and works in Madrid since 1954, when he moved from the small city in the north of Spain where he spent his childhood and early youth to begin his university education. Since then, […]

Rafael Moneo (born in Tudela, Navarra, 1937) has lived and works in Madrid since 1954, when he moved from the small city in the north of Spain where he spent his childhood and early youth to begin his university education. Since then, short time periods have suspended his attachment to Madrid, a city that becomes crucial when one begins to investigate Moneo’s body of work. After qualifying as an architect in 1961, Moneo moved to Hellebaek in Denmark to work for Jørn Utzon. He returned to Madrid a year later for a short stay before moving to Rome, where he spent two years at the Spanish Academy, a wilful period to reflect upon theory and history and the place where he would establish his first linkages with the Italian scenario. In Rome he met Manfredo Tafuri, Paolo Portoghesi, Bruno Zevi (1) and Rudolf Wittkower, amongst other Italian architects and historians. It was not until 1967, back in Spain, where he met Aldo Rossi for the first time in one of the encounters organised by members of the Schools of Barcelona and Madrid, named as the Pequeños Congresos (“small conferences”).

Rossi’´s The architecture of the City was immediately translated into Spanish and published by Barcelona-based editorial and publishing house Gustavo Gili in 1971 (2). Architect and professor Salvador Tarragó translated the book (3) and promoted at once the ‘`Rossian’´ magazine 2C Arquitectura de la Ciudad (4), publishing three issues on Rossi. Other publications from Barcelona played an important role as printed spaces committed to the endeavour of disseminating architectural theory, transforming their previous condition as mere descriptive elements of a more and more confusing urban reality, into spaces where this reality was discussed for transformation. They became vehicles through which a new consideration of the city as collective space of action would be conceived, engaging with Rossi’´s main statement as to consider the city – and every urban artefact – to be by it’s very nature, collective.

Moneo wrote a paper for 2C on Rossi in one of the aforementioned monographs (5). 2C was contemporaneous of another magazine published in Barcelona during the late 70s, Arquitecturas Bis, información gráfica de actualidad (6), of which Moneo was one of the founding members. One of the first contents Moneo wrote for AB was an essay on Rossi and Vittorio Gregotti (7), which introduced a larger investigation on the former’s work, including a discussion of the principles Rossi made explicit on his book. AB stood out from other magazines published in Spain partly due to its connections with several North American and Italian publications, such as Oppositions from New York and the Milanese Lotus. They practiced an ‘after-modern’ philosophical and historical self-consciousness that contributed to a breaking with the traditions of modernism: theory was understood as a form of practice in its own right. The publication in Oppositions of “Aldo Rossi: The Idea of Architecture and the Modena Cemetery” (8) translated Rossi’s ideology, and what was known as ‘architettura autonomia’ (9), to the North American intellectual environment. In 1985, when the last issue of AB was published, Moneo was already working as Chairman of the Department of Architecture at Harvard University and his role as active translator of Rossi’s ideas into North American academia was by then firmly established.

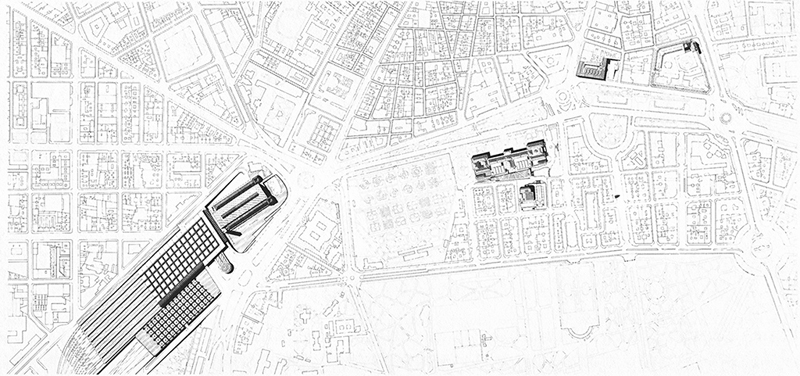

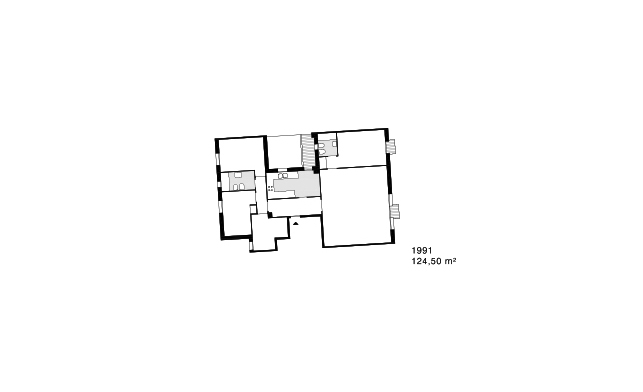

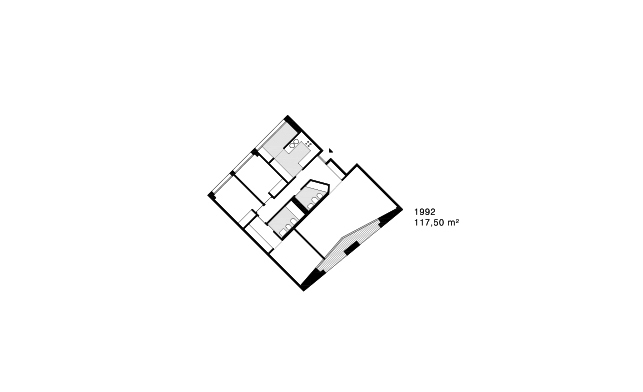

On his return to Spain, between 1991 and 1992 (10), Moneo was working on two projects in Madrid: the new Atocha Station (11) and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum (12). Both are purposefully and carefully redrawn in the city plan; together with the Bank of Spain (13) and the Prado Museum extensions (14). Atocha, which has recently been extended again, according to Moneo’s design, turns out to be the architecture capable of synthesising most accurately Moneo’s approach to what Rossi described as “the complexity of urban artefacts”. Its design strategy is the assertion of the concept of the city as a totality. The aim was to confer consistency, order and continuity to an urban complex comprising several different parts: the old station, with the preservation of its late nineteenth-century marquee; a new car park area just above the new suburban station; the intercity station, built around and defined according to the original alignment of tracks; and the intermodal transportation hub that manifests itself as the centerpiece of the architecture resolving Atocha’s complexity, as stated by Moneo (15). The hub reveals itself as a primary element, a permanent structure that ties together the complexity of all the overlapping layouts, movements and directions, but which above all determines and shapes the city. It also unveils what Rossi would describe as the contrast between private and universal, individual and collective, and emerges, like a metaphysical piece inside a painting by de Chirico, as a monument defined by Rossi standing within the landscape of Madrid. Moneo, as constructor of the city whose main intellectual vehicle is history – understood as the accumulation of human experience over time – was concerned with the notion of continuity and permanence, assuming that the city, as Rossi emphasised, endures through its transformations.

1 Moneo translated into Spanish Bruno Zevi´s 1964 edition of Architecture in Nuce [Architettura in nuce]. ZEVI, Bruno (1969) Arquitectura in Nuce. Una definición de arquitectura. Madrid: Aguilar.

2 Unlike in the United States, where the book was published more than a decade later: ROSSI, Aldo (1982) The Architecture of the City. Translation by Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman, and Introduction by Peter Eisenman; revised for the American edition by Aldo Rossi and Peter Eisenman. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

3 ROSSI, Aldo (1971). La arquitectura de la ciudad. Translation by Josep María Ferrer-Ferrer and Salvador Tarragó Cid. Colección “Arquitectura y Crítica”. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

4 2C Construcción de la Ciudad published a total of 22 issues from 1972 to 1985. Directed by Salvador Tarragó and Carlos Martí Arís.

5 MONEO, Rafael (1979). “La obra reciente de Aldo Rossi: dos reflexiones”. 2C Construcción de la Ciudad n. 14. December of 1979. Barcelona: Coop. Ind. De trabajo Asociado “Grupo 2C” S.C.I. Pages 38-39.

6 Arquitecturas Bis: información gráfica de actualidad was published in Barcelona from 1974 to 1985, editing a total of 52 issues. The magazine arranged a very efficient intern structure that actively participated in the production and edition of all the numbers, generating around 500 writings; about 30% of the total content (from news notes, theoretical and criticism writings, texts and book reviews). Under the direction of well-known publisher Rosa Regás, the editorial board was mainly made up by architects and professors – Oriol Bohigas, Federico Correa, Manuel de Solà-Morales, Rafael Moneo, Lluís Domènech, Helio Piñón, and Luis Peña Ganchegui (the latter a member since the 17-18 double issue published in July and September of 1977) – as well as the philosopher Tomás Lloréns and the graphic designer Enric Satué. From 1977, the architect Fernando Villavecchia joined as the Editorial Board secretary.

7 MONEO, Rafael (1974). “Rossi & Gregotti”. Arquitecturas Bis n. 4 (November 1974). Barcelona: La Gaya Ciencia.

8 “These notes, written in 1973 before the Triennale of 1974, do not deal with the complex notions which provoked that exhibition; with the grouping under the banner of the ‘Tendenza’ – a heterogeneous, yet consciously selected, group of architects from different countries. Thus these notes are limited to the discussion of Rossi’s principles made explicit in his book L´Architettura della Città, and in this light, to see how Rossi designed the Modena Cemetery without considering the propositions inherent in the Triennale even though Rossi was undoubtedly the inspiration for these ideas.” MONEO, Rafael (1976). Aldo Rossi: “The Idea of Architecture and the Modena Cemetery”. Oppositions n. 5. A Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture. Summer 1976. New York: Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies. [Original: MONEO, Rafael (1974) “La idea de Arquitectura en Rossi y el Cementerio de Modena”. Barcelona: Ediciones de la ETSAB].

9 […] “Moneo makes the connection between the two aspects inherent in Rossi’s work by breaking the article into two dialectic halves: each with its own theme and its own rhythm and cadence. The first part, which dissects Rossi’s thinking in his book The Architecture of the City, is more intense; the second part, which examines Rossi’s project for the Modena cemetery, is more lyrical. For me, this is architecture writing at its best – dense and informative, analytical and questioning. There is no question that Rossi’s metaphysics demand this kind of dissection. Equally important for the European context is the fact that such an article by Moneo, who was part of the Barcelona group of writers of the magazine Arquitecturas Bis, signals a possible change in the Milan/Barcelona axis: from the influence in the early sixties of Vittorio Gregotti and post-war functionalism to the new ideology present in Rossi’s work” […]. EISENMAN, Peter (1976) Prologue to Moneo’s text “The Idea of Architecture and the Modena Cemetery”. Ibid.

10 During his professorship at the School of Barcelona, Moneo continue living and working in Madrid, commuting to Barcelona to teach every week. During this time he developed two important works: the Bankinter Building in Madrid (1972-76) and Logroño town hall (1973-81). During his years at Harvard, as Chair of the Department of Architecture, from 1985 to 1990, Moneo moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, with his family, and although he opened a small office in Massachusetts Avenue, near Harvard Square, the main office remained in Madrid.

11 Atocha Station extension, Madrid (1984-92). In collaboration with Emilio Tuñón. First prize winner in competition (1983). Phase I (1985-88): Suburban Station and Intermodal transportation hub. Phase II (1988-92): Intercity station and s. XIX marquee building (architect Alberto Del Palacio, 1894). Phase III (2008-2010): Extension of the intercity station.

12 Renovation of the Palace of Villahermosa: Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. 1989-1992.

13 Bank of Spain extension (competition winner, 1978-80, built in 2004-06).

14 Prado Museum extension (first prize in competition 1998, 1998-07).

15 MONEO, Rafael (2010). El Croquis n.20+64+98: Rafael Moneo: imperative anthology, 1967-2004. El Escorial, Madrid: El Croquis Editorial, p. 206-223.

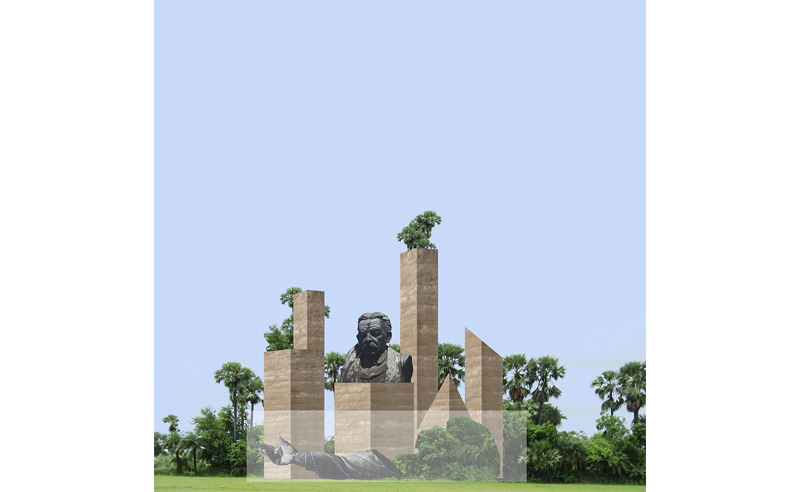

GANKO

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS Monuments and the Theory of Permanences “There is nothing new in all of this. Yet in attempting to formulate a theory of urban artifacts that is consistent with reality, I have benefited from highly diverse sources.” Monuments and the Theory of Permanences concludes the first chapter of […]

“There is nothing new in all of this. Yet in attempting to formulate a theory of urban artifacts that is consistent with reality, I have benefited from highly diverse sources.”

Monuments and the Theory of Permanences concludes the first chapter of The Architecture of The City. Among the four chapters of the book, this is the only one in which Rossi succeeds in restraining the centrifugal tendencies of its discourse. By virtue of a great effort of synthesis, here, Rossi achieves important results.

With Monuments and the Theory of Permanences a particular idea of the city’s place in relation to the ordinance of time reaches its ultimate formulation. This idea sets-up the (unfulfilled) premise for a theory of the city where new and old parts – suburbs and town centers, mediocrity and monumentality – become part of a progressive and unitary plan embracing “all” the contemporary city.

With Monuments and the Theory of Permanences, Rossi takes distance from the simplifications of both modern utopias and postmodern nostalgias in order to explore the complexity of the contemporary city; its technical advancements as well as the memory deposited in it throughout history.

With Monuments and the Theory of Permanences – in accordance to what Rossi calls: “consistency with reality” – both past and future per-se are rejected as moments detached from the concrete experience of life. Yet, for the sake of a deeper understanding of the present, past may prove of particular interest.

“One must remember that the difference between past and future […] in large measure reflects the fact that the past is partly being experienced now, and this may be the meaning to give permanences: they are a past that we are still experiencing.”

At the very same time, to the extent that it exerts passive resistance towards new forms of appropriation, the past ( i.e. the monumental structure of the city) is felt by Rossi as the equivalent of a pathological condition; an obstacle to the pursuit of one’s duties and pleasures.

“In this respect, permanences present two aspects: on the one hand, they can be considered as propelling elements; on the other, as pathological elements.”

Rossi’s position regarding the time of the city is problematic:

“The form of the city is always the form of a particular time of the city; but there are many times in the formulation of the city, and a city may change its face even in the course of one’s man life, its original references ceasing to exist.”

However, a comparison with traditional ones can enlighten Rossi’s stance. “Earlier urban thinking had placed the modern city in phased history: between a benighted past and a rosy future (the Enlightenment view) or as a betrayal of a golden past (the Romantic view).” According to Rossi “[…] by contrast, the city [has] no structured temporal locus between past and future, but rather a temporal quality. The modern city offer[s] an eternal hic et nunc, whose content [is] transience, but whose transience [is] permanent. The city present[s] a succession of variegated, fleeting moments, each to be savoured in its passage from nonexistence to oblivion.” (1) According to Rossi, the present is not simply the point of transition between past and future, but rather the point of convergence of multiple pasts and possible futures. Therefore, it cannot be judged in terms of “progress” or “decadence”. In this context monuments play a particular role, as the formal infrastructure allowing for the permanence, as well as the sudden reappearance of a collective sacred memory within the otherwise profane character of modern civilization. Suspended in a state of eternal present, according to Rossi, monuments mediate between permanence and change, past and future, playing both a conservative and a propelling role.

“I mainly want to establish […] that the dynamic process of the city tends more to evolution than preservation, and that in evolution monuments are not only preserved but continuously presented as propelling elements of development.”

Rossi’s theory of permanence brings together two conflicting concepts of the city’s evolution. A positive idea of the city as progress inherited from authors like Voltaire, Fichte and Mumford – the city as the culture-forming agent par excellence; the site as well as the symbol of civilization – is blended with the fatalism of a concept of the city as destiny – the city as “[…] a collective fatality which could know only personal solutions, not social ones.” (2) – influenced by the kulturpessimismus of Burckhardt, Spengler and Beaudelaire.

As distant as it is affected by both utopia and nostalgia, the ambiguous stance toward one’s own time outlined by Monuments and the Theory of Permanences is a difficult whole seeking a tricky reconciliation of opposites. Nevertheless, Rossi’s idea of “consistency with reality” is not only the main achievement of The Architecture of the City. Also, it is still a realistic work hypothesis.

1 Schorske, E. Carl, “The Idea of the City in European Thought: Voltaire to Spengler”, in Burchard, John E., Handlin, Oscar, eds., The Historian and the City, Cambridge, Mass., 1963, p. 109. In the original text Schorske is referring to Charles Beaudelaire. The French poet is a fundamental reference for Rossi’ theory and is explicitly quoted at the end of the paragraph.

2 Schorske, E. Carl, p.111. In this case Schorske is referring to the conception of the city of the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke.

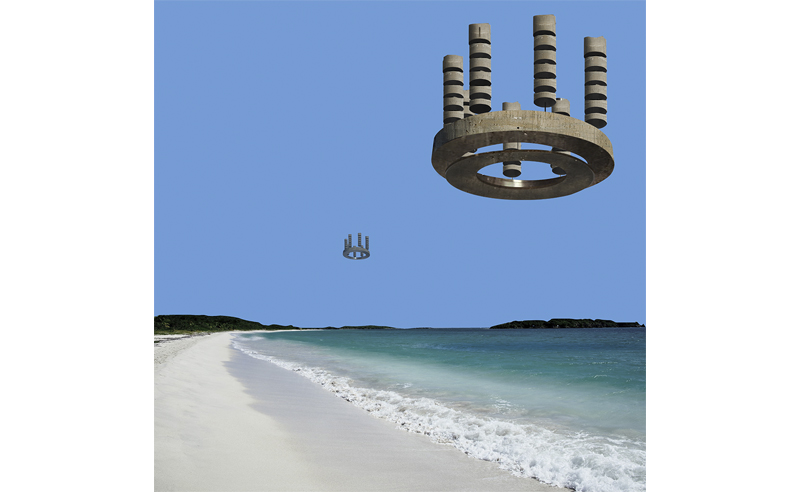

Armin Linke

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA The Study Area Armin Linke (born 1966, lives in Berlin) combines a range of contemporary image-processing technologies to blur the borders between fiction and reality. His artistic practice is concerned with the interrelations and transformative powers between urban, architectural or spatial functions and the human […]

Mountain with antennas Kitakyushu Japan

Irina Davidovici

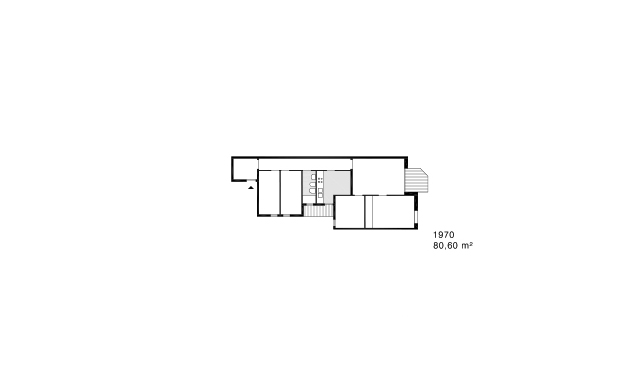

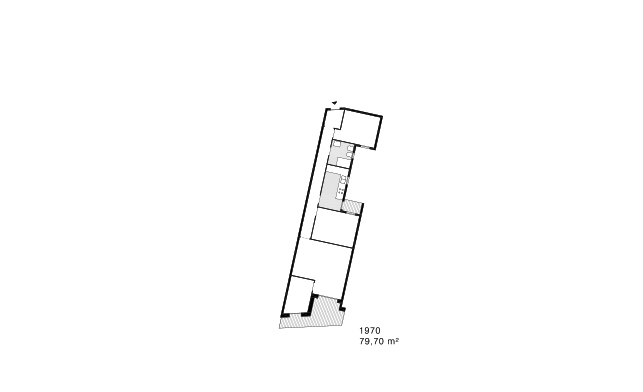

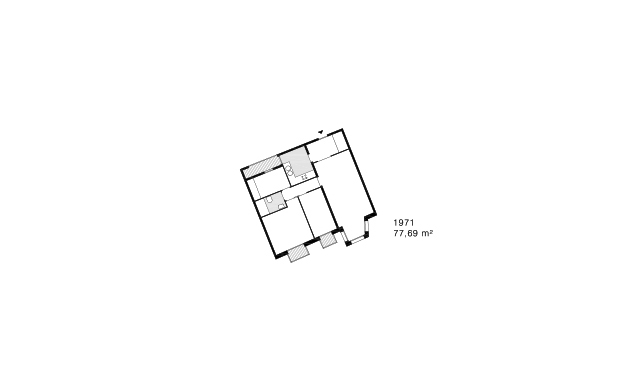

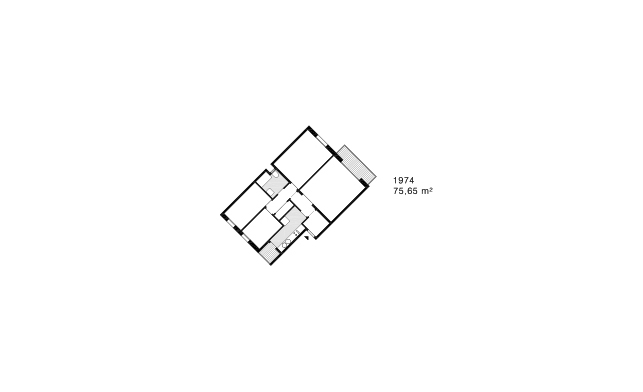

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA Residential Districts as Study Areas In Rossi’s studio at ETH Zurich between 1972 and 1974, students were asked to produce detailed surveys of the city’s central districts. The analysis of historical urban fabric in its existing form was part of a design methodology based on […]

In Rossi’s studio at ETH Zurich between 1972 and 1974, students were asked to produce detailed surveys of the city’s central districts. The analysis of historical urban fabric in its existing form was part of a design methodology based on typology, which he cultivated as a practical application of Architettura della Città. Based on the premise that the chapter “Residential Districts as Study Areas” was a theoretical precursor to Rossi’s ETH semesters, it is possible to review the Zurich of today in relation to Rossi’s 1966 text.

Seen conceptually, Zurich’s ascendance to a global status is consistent with a pattern correlating political events, physical changes in the urban fabric, and population growth. Throughout its history the city was animated by an impulse towards centrifugal expansion. In the sixteenth century, the militant effort to impose the Reformed faith on other cantons rendered Zurich the centre of Protestant Switzerland, lending it a Europe-wide significance. In the nineteenth century, its drive for political reform and modernisation led to Zurich hosting two important federal institutions, the Polytechnikum and the first section of the railways, both programmatic elements for the creation of a unified, modern Switzerland. In 1855, the same year the Polytechnikum was founded, the medieval walls were torn down, initiating a long-term trend of urban expansion. 19 outlying municipalities were politically incorporated in a first stage in 1893 and a second one in 1934, practically doubling the size of the city. At the same time the population increased greatly with industrialization and the creation of large factory quarters, both along the railways and to the north and west of the main city.

This process of urban growth underlines the creation of what Rossi calls “residential districts”: characterful, relatively small areas, clearly distinct from each other yet stitched together into an urban collage. Zurich’s heterogeneity provides an excellent illustration of the Rossian city as “a system” of “relatively autonomous parts”, “each with its own characteristics” (1). In Zurich these “parts”, each with its own personality, are at the same time familiar equivalents of pan-European urban tableaux. The narrow, winding medieval streets of the historical core, the palatial grandeur of the tiny old banking district, the working-class housing colonies of Red Zurich, 1930s stone-clad rationalist institutions and 1950s residential towers appear like conceptual miniatures of European urban episodes. Like a precursor of Rossi’s later Città analoga collage, Zurich thus becomes a cabinet of urban fragments, each with its raison d’être and own limited order.

Since the city is so small, the various cityscapes occur in restricted territories, sometimes only a few hundred meters long and a couple of streets wide. Characteristically of Zurich, the borders between these districts, be they natural or man-made, are prominent and final. The natural constraints that first defined the settlement, two low mountain ranges and the glacial lake between, have continued to shape its development leading to a paradoxical, “bipolar” growth. When natives refer to the split structure of their city, they perceive a rift between one unit formed by the historical centre and its immediately adjacent quartiers, and another comprising industrial and postindustrial growth to the West and the North. The northern expansion towards Schwamendingen, the Oerlikon industrial district and Kloten Airport is interrupted by the artificial rural idyll of Zürichberg, a carefully untouched, forested hill overlooking the city. Its introverted culture of exclusive villas, little isolated farmyards and luxury hotels is replicated by the smaller settlements stringing southwards along the shores of Lake Zurich. Together they signal the formation of a “clear topography of prosperity” centered around central Zurich and extending to the so-called Goldküste along the sunny side of the lake (2).

Zurich’s division along the central and northern development nodes does not presuppose either is a unity. The centre is profoundly divided, sliced three ways by the river Limmat, its confluence with the river Sihl, and the wide stretch of railway that cuts across the western side of the city. In its dimensions and decisiveness, the presence of this transport infrastructure is equivalent to that of a third river in the way it cuts across the industrial city fabric. In contrast to the tendency of great European cities to conceal the railways beneath raised parapets and under ground, here they are on display, structuring the urban fabric and influencing the way people move through the city. The new apartment and office towers built along this stretch are oriented towards a panoramic view grounded by a field of steel rails, its horizon underlined by parallel cables and passing trains.

The character of the medieval centre and that of the nineteenth-century bourgeois and industrial residential districts and the contrast between modernist insertions and the gentrified old factory quarters attest to the fact that Zurich’s heterogeneity is not the effect of simple functional zoning. Rossi’s reading helps us understand that Zurich is an assembly of “morphological and structural units, [each] characterized by a certain urban landscape, a certain social content, and its function” (3). Its characteristic heterogeneity is the prerogative of residential districts as “complex urban artifacts”, densely grouped together yet abruptly separated into distinct units of collective meaning.

1 Rossi, 1966, 65.

2 Roger Diener, Jacques Herzog, Marcel Meili, Pierre de Meuron, Christian Schmid. Studio Basel, Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, Birkhäuser 2006, 618-620.

3 Rossi, 1966, 65.

Martin Marker Larsen & Christian Vennerstrøm

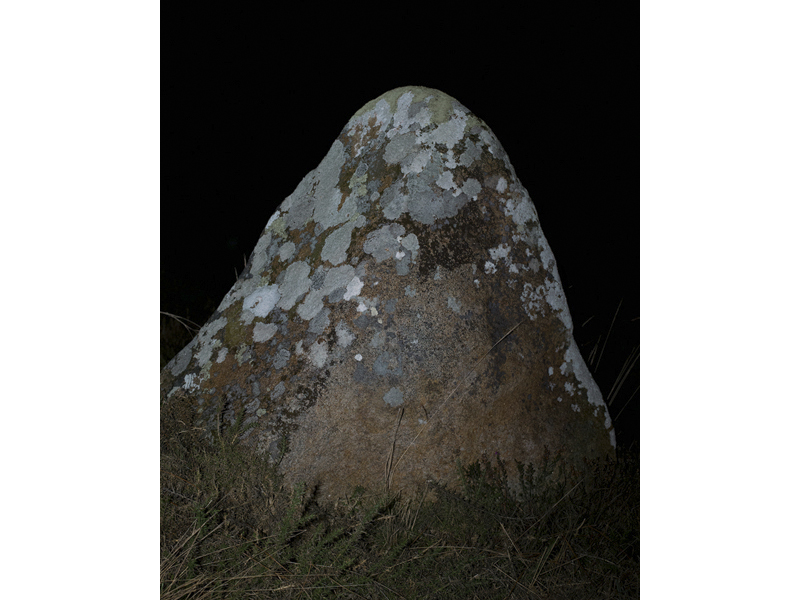

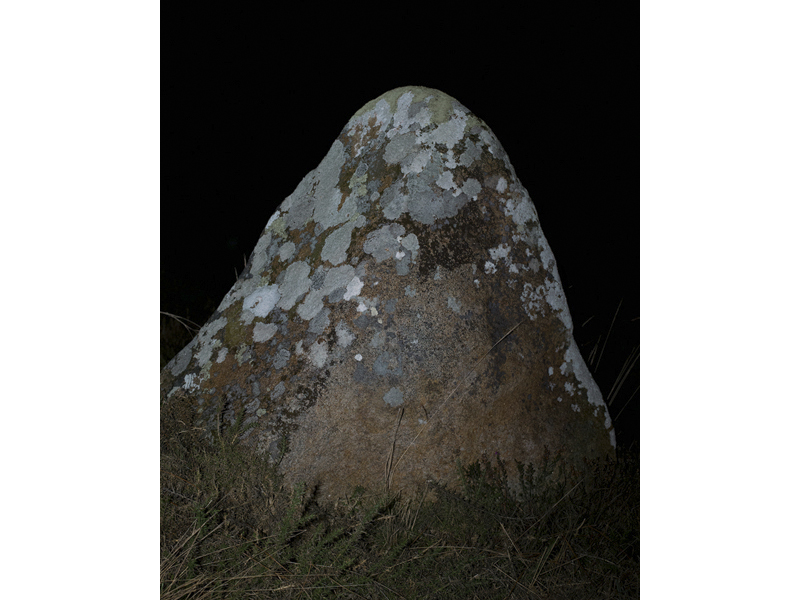

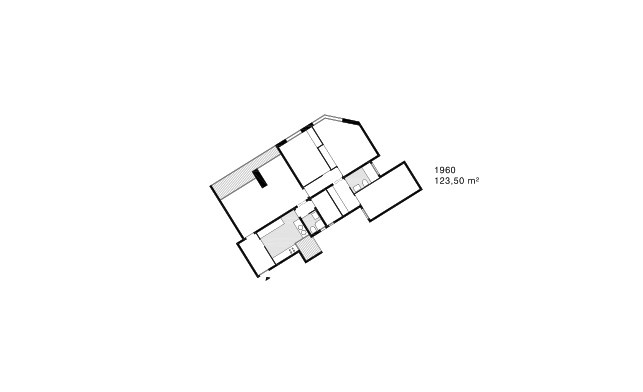

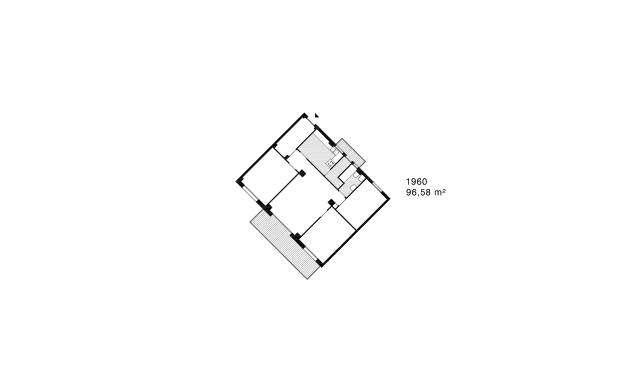

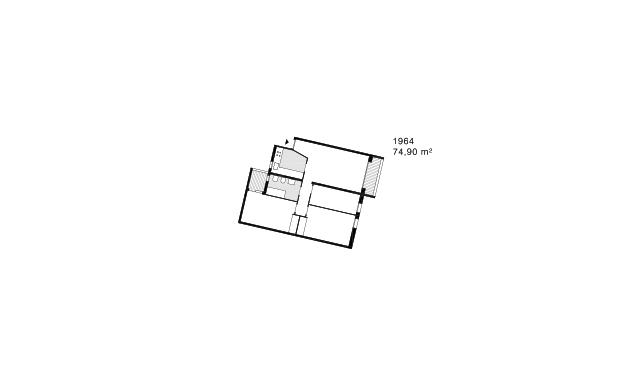

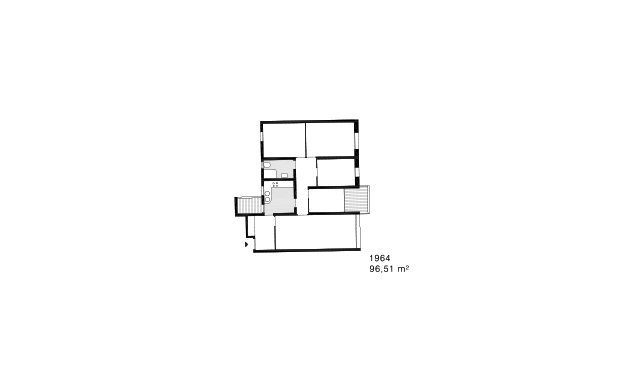

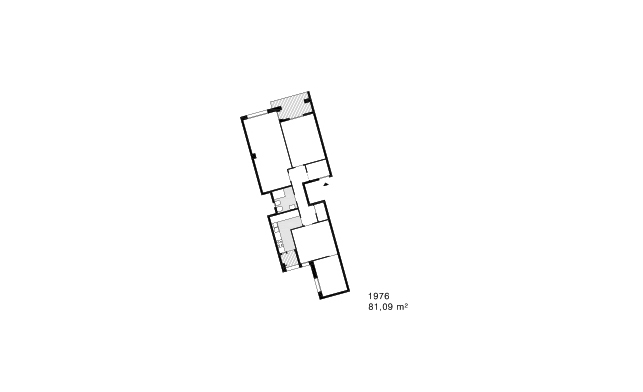

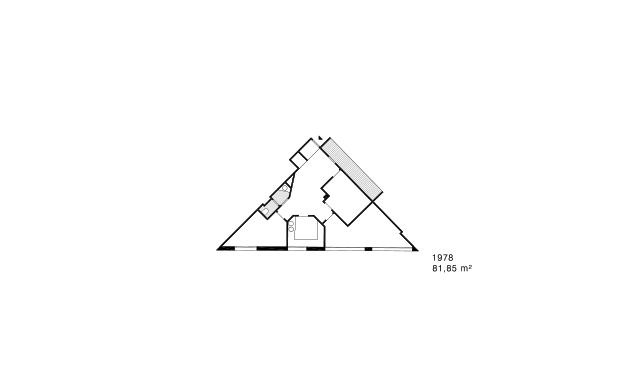

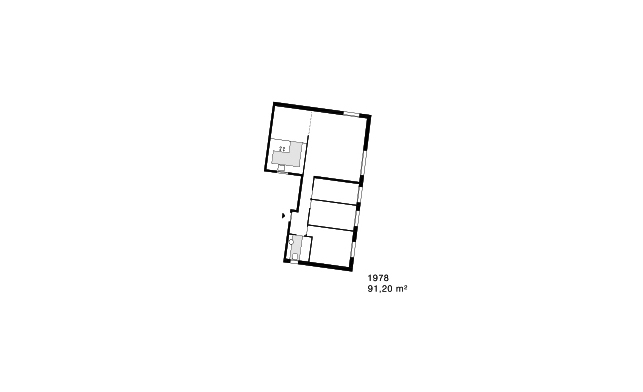

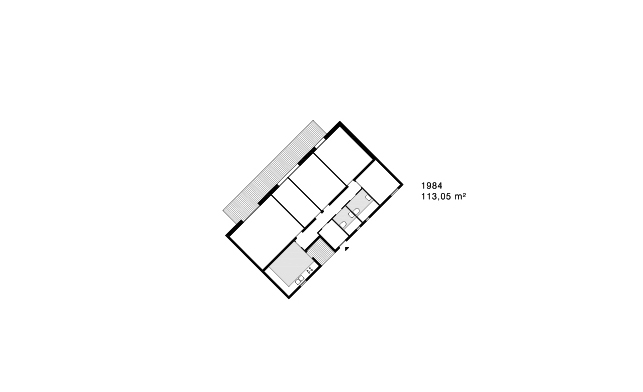

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA The Individual Dwelling The following are simple thoughts, images and a bit of text that have been travelling between Switzerland and Bahrain in the summer of 2016. The starting point was a series of images capturing the simple fact that over the last 40-50 years […]

The following are simple thoughts, images and a bit of text that have been travelling between Switzerland and Bahrain in the summer of 2016. The starting point was a series of images capturing the simple fact that over the last 40-50 years the town of A’ali has grown in size and density expanding into the ancient burial fields of Bahrain. Many thousands of single person or family sized mounds have been cleared to make space for new infrastructure and housing. Several mounds have been significantly altered to make space for private parking and roads. Some grave chambers have been exposed to the city while others have been half way dissected leaving only a few cuts open and the remaining mound intact. The static mounds have become a part of a dynamic web of relations and interrelations that flow within a contemporary city. This cohabitation affects not only the city, but also these structures. The result is an interesting relation between something as dynamic as life and something as static as death.

By being part of the city these burial places becomes part of the collective unconsciousness. Like churches or monasteries they are simple signs, static urban facts and yet they are undeniably part of the everyday life surrounding them. Maybe the contemporary life needs these stable points to establish a relation to death. But why should a permanent place be important to the dead when the living that keep their memories alive are constantly moving around in a non-permanent way. Everything is now mobile and negotiable. Even death is now fluid and dissolvable.

We keep making piles into cities.

Cities become piles upon piles.

And cities become new cities

new cities upon old piles.

Cities are made from piles

upon bodies.

New houses are build around the body.

Around the body and the needs of the body.

For practical reasons or

for the reason of no practical reason.

New houses become old houses.

Keys, nameplates and addresses change hands

as cities are smouldering.

And cities are smouldering

back into piles upon bodies.

Letting go of being

like old skin falling.

When all has settled

and the air is clear

stands a new in its place

seemingly alike.

The form of

graves and faith

heavy and stabile

make beds and cover.

It vibrates inside time and falls apart.

In un-expected frequencies

it all falls into piles.

The question is whether our perception of signs is ready to change with the same speed and dynamics as everything surrounding us.

Something Fantastic

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA The Typological Problem of Housing in Berlin Something Fantastic is a design practice founded by three architects, Leonard Streich, Julian Schubert and Elena Schütz. The firm’s agenda is based on the idea that architecture is affected by everything and vice versa – does affect everything […]

Camille Zakharia

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA Garden City and the Ville Radieuse Camille Zakharia graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from NSCAD University Halifax Canada in 1997 and a Bachelor of Engineering from the American University of Beirut in 1985. Zakharia has exhibited prolifically across North America, Europe and the […]

Shumon Basar

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA Primary Elements I’ve been living in a special slice of building made from squares, cylinders, rectangles and triangles. These shapes can be child-like or Platonic; abstract, or figurative. For the architect, John Hejduk, they are probably all of these. Hejduk will be well known to […]

I’ve been living in a special slice of building made from squares, cylinders, rectangles and triangles. These shapes can be child-like or Platonic; abstract, or figurative. For the architect, John Hejduk, they are probably all of these.

Hejduk will be well known to those within the architectural field but not to those outside it. He built very little in his lifetime; not because he couldn’t, but rather, because he chose not to. Instead, he made scratchy drawings of carnivalesque objects wandering Europe. His work constituted a diaspora of subjects and objects. A cast-list of melancholia. He wrote many, many poems. He constructed strange installations – also comprised of collages of primary shapes but wrought into animistic life.

He taught, lots. In fact, he said, “I don’t make any separations. A poem is a poem. A building’s a building. Architecture’s architecture. Music is music. I mean, it’s all structure. It’s structure.” And yet I find myself residing in a tower where separation is apparent I’ve been residing on the 10th and 11th floors of a former social housing block in Berlin that he architected, where separation is apparent: each room exists in its own independent tower, linked to each other by short, punctuated walkways. The gaps are vantage points from which the city enters the building, or, you embody the city.

Again, AND, not OR. The apartment oscillates between spaces that seem “too big” and “too small.” It reminds us we only become conscious of space when it is either too big (a cathedral, a palace) or is too small (a railway cabin, a prison cell). For most of us, lived space happens in the middle ground and, as such, washes over us quietly. But not here. There are only seven apartments in total in the building. Fourteen floors. It’s utterly irrational – no other developer would condone it – and therefore utterly compelling.

Commissioned by the IBA (Internationale Bauausstellung Berlin) initiative, and finished in 1988 a year before the (nearby) Berlin Wall came down, this piece of pure auteurship stands alone, apart, even from itself. Metallic stars protrude from the outer walls, silently and regularly arrayed. Why? The most convincing story I’ve heard is that: “They’re grips for angels to hold onto when they climb the sides of the tower.” (Hejduk was a scholar of angelology.)

Every day when I wake up inside this piece of literature masquerading as architecture, a spectral pulse runs through me. This has been home. I have been a character, another primary form amongst others, visible and invisible. Life here is enchanting and unnerving. It is the force of incisive simplicity, the crisp composition of singular ideas.

Cino Zucchi

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA The Dynamic of Urban Elements Cities stand. Their stones stand up; they remain still, obeying to the laws of statics. What is then moving? Their inhabitants running around undertaking their daily activities, the flags flapping on their poles, the clouds casting shadows on their moldings […]

Cities stand. Their stones stand up; they remain still, obeying to the laws of statics. What is then moving? Their inhabitants running around undertaking their daily activities, the flags flapping on their poles, the clouds casting shadows on their moldings and cobblestones.

A bowl contains soup, but it is made of a different material from its content. Its shape is apt to support a dense liquid and hold its heat for a certain time, but it obviously survives beyond this particular lifespan; and it could be used for very different goals from the ones it was planned for.

The famous quote by Winston Churchill “we shape our buildings, thereafter our buildings shape us”, can be applied to bowls and cities as well, in a sort of mirror-image version of the other famous motto, “from the spoon to the city”. If the latter states that the form of human artefacts is the result of a unified work-style of a supposedly ‘modern’ designer, the former casts light on how much people’s lives and behaviours are invisibly guided by the spaces in which they take place.

Are we molluscs custom-producing our own homes or are we rather hermit crabs, looking for an empty shell to host our soft body, and migrating from one to another when the previous one is not fit for purpose any more?

On the two sides of the Atlantic Ocean, and from two very different points of view, in the sixth decade of the last century two different people discovered, or rather rediscovered, the ‘stillness’ of the city, and in a way also the autonomous character of its elements: Aldo Rossi and Kevin Lynch.

Akin to a moment in a game of musical statues or a freeze-frame video-clip effect, their written and illustrated pictures created a snapshot of the material part of the city. Or better, they froze only some of its elements, specifically those ones that could appear in the memories and the minds of more than one of its inhabitants. If remembrance is a subjective power, they attributed this privileged state only to things and images that appeared in collective mental maps.

Both Lynch and Rossi understood that this condition of permanence of the physical body of the city was a shared need. It somehow coincided with the notion of ‘habit’, of convention, of custom, and more generally with the public realm. Stillness is what founded the city as a public artefact, and prevented its spaces from being the mere result of the Brownian movement of its occupants and vehicles.

In the planning and urban design of the sixties and seventies, urban form was typically seen as the final output of a process where a series of data and inputs had to be enhanced via the means of the ‘black box’ of a planning or design ‘method’ (1). Following this attitude, the issue of form had no real consistence, since in the end it was just the solidification of a functional diagram: Walter Gropius’ speech at the Brussels Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in 1930 on the dilemma of whether to build “Low, Mid- or High-Rise Buildings?” advocated the latter of the three solutions, on the grounds of increased sun exposure and building economy issues. (2)

If the Italian word ‘monumento’ refers explicitly to the role of a building as a reminder of a historical event or of a powerful ruler, the English word ‘landmark’ overlooks issues of content and emphasises instead its mere physical relevance; according to Wikipedia, it is “a recognisable natural or artificial feature used for navigation, a feature that stands out from its near environment and is often visible from long distances.” The contemporary meaning of this word is therefore very close to what Rem Koolhaas defines as ‘Automonument’. (3)

The wanderings of Boston pedestrians in Lynch’s The Image of the City (1960) or of the four-wheeled amniotic sacs in his The View from the Road (1965) need landmarks to orient themselves in the flux of the metropolis; be them grain elevators (already represented as monuments by Le Corbusier in Toward an Architecture (1923), the dome of Washington’s Capitol (not so dissimilar from the one that Albert Speer designed for Hitler to complete Berlin’s grand axis; often the architectures of political opposite systems are disturbingly similar) or a sketch of the 1939 New York World’s fair Trylon and Perisphere structures, they represent the necessitated visual pointers in the extended geography of the new territory.

If cars flow around the fixity of the ‘Monument/Automonument/Landmark’ in Lynch’s continuous ‘Space’, little armies of masons and carpenters climb on them in Aldo Rossi’s seamless ‘time’. His conception of the Monument is a lively one, as its ‘autonomous’ form – whose founding elements are typological simplicity, significant mass, and formal clarity rather than stylistic issues – seems to ignite in successive generations of urbanites realizations of unexpected potentials. The original title of Aldo Rossi’s chapter is actually “Tensione degli elementi urbani”, where ‘tension’ is still a term belonging to the discipline of Statics before the one of Dynamics.

Rossi’s monuments are peculiar points in the urban structure, enduring in their ‘final’ incarnation whilst at the same time endlessly reworked over, like the never-ending story of the Fabbrica del Duomo in Milan or the plans by Pope Sixtus V to convert the Colosseum into a housing block containing a wool mill.

The monument is still, yet the monument also stirs the dynamics of urban mutation, and focuses attention on the patterns of the open public spaces around it. It is a clear and simple concept; but as with other ‘necessary’ ones, it re-emerges periodically from the sea of intellect like a wandering whale.

In fact, the dialectic between the structured body of the monument and the flowing paths of its visual and cognitive perception was masterfully expressed seventy years before the first edition of Rossi’s The Architecture of the City, by a twenty-three year old writer who was asked by the magazine La Nouvelle Revue to write something about the work of Leonardo da Vinci. Although puzzled by his output, they had the courage to publish his astounding ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’:

“The monument (which composes the City which in turn is almost the whole of civilization) is such a complex entity that our understanding of it passes through several successive phases. First we grasp a changeable background that merges with the sky, then a rich texture of motifs in height, breadth and depth, infinitely varied by perspective, then something solid, bold, resistant, with certain animal characteristics – organs, members – then finally a machine having gravity for its motive force, one that carries us in thought from geometry to dynamics and thence to the most tenuous speculations of molecular physics, suggesting as it does not only the theories of that science but the models used to represent molecular structures. It is through the monument or, one might rather say, among such imaginary scaffoldings as might be conceived to harmonise its conditions one with another – its purpose with stability, its proportions with its site, its form with its matter, and harmonising each of these conditions with itself, its millions of aspects among themselves, its types of balance among themselves, its three dimensions with one another, that we are best able to reconstitute the clear intelligence of a Leonardo. Such a mind can play at imagining the future sensations of the man who will make a circuit of the edifice, draw near, appear at a window, and by picturing what the man will see; or by following the weight of the roof as it is carried down walls and buttresses to the foundations; or by feeling the balanced stress of the beams and the vibration of the wind that will torment them; or by foreseeing the forms of light playing freely over the tiles and corniches, then diffused, encaged in rooms where the sun touches the floors. It will test and judge the pressure of the lintel on its supports, the expediency of the arch, the difficulties of the vaulting, the cascades of the steps gushing from their landings, and all the power of invention that terminates in a durable mass, embellished, defended, and made liquid with windows, made for our lives, to contain our words, and out of it our smoke will rise.

Architecture is commonly misunderstood. Our notion of it varies from stage setting to that of an investment in housing. I suggest we refer to the idea of the City in order to appreciate its universality, and that we should come to know its complex charm by recalling the multiplicity of its aspects. For a building to be motionless is the exception; our pleasure comes from moving about it so as to make the building move in turn, while we enjoy all the combinations of its parts, as they vary: the column turns, depths recede, galleries glide; a thousand visions escape, a thousand harmonies.” (4)

Once written, texts are like monuments; they need to stand still to allow our minds to move around them, and appreciate “the balanced stress of the beams and the vibration of the wind, which will torment them”. (5)

“A rose is a rose is a rose”, and The Architecture of the City is the architecture of the city: It has built our image of a prototypical urban environment, it has helped us to give a bold form to a series of scattered realisations of the true nature of the built environment; bold and at the same time ever-changing, the beloved backdrop of our busy lives.

1 See for example the circular town planning schemes in Victor Gruen, The heart of our cities: The urban crisis: diagnosis and cure, New York, Simon and Schuster, 1964, the mathematical formulas and the discussion on modelling and urban planning in Leslie Martin and Lionel March editors, Urban Space and Structures, Cambridge University Press, London/New York, 1972, ISBN 0521084148, or the conceptual diagrams contained in Serge Chermayeff, Alexander Tzonis, Shape of Community, Italian translation La forma dell’ambiente collettivo, Il Saggiatore, Firenze 1972.

2 Walter Gropius, Flach — Mittel — oder Hochbau?, speech at the CIAM, in Rationelle Bebauungsweisen, 1931, pp. 26-47, English translation as Id., Houses, Walk-ups or High-rise Apartment Blocks?, in The Scope of Total Architecture, MacMillan Publishing Company, New York, 1980.

3 “Beyond a certain critical mass each structure becomes a monument, or at least raises that expectation through itssize alone, even if the sum or the nature of the individual activities it accommodates does not deserve a monumental expression. This category of monument presents a radical, morally traumatic break with the conventions of symbolism: its physical manifestation does not represent an abstract ideal, an institution of exceptional importance, a three-dimensional, readable articulation of a social hierarchy, a memorial; it merely is itself and through sheer volume cannotavoid being a symbol – an empty one, available for meaning as a billboard is for advertisement.” Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York. A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan, 1978, new editionThe Monacelli Press, New York 1994 ISBN 1885254·00-8, p.100.

4 Paul Valéry, Introduction à la méthode de Léonard de Vinci, in “La Nouvelle Revue”, 1985, pp.742-770, English translation from Paul Valéry, An Anthology, Selected, with an Introduction, by James R.Lawler, from The Collected Works of Paul Valéry edited by Jackson Mathews, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London and Henley, 1977 ISBN 071008806X, pp.79-81.

5 See previous reference.

Giovanna Silva

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA The Ancient City Giovanna Silva is based in Milan. She worked for Domus and Abitare as photographer and photoeditor. She is founder of San Rocco magazine and Humboldt Books publishing house.. She has published several books on her projects, both with Italian and international publishers, among which Mousse Publishing and Bedford Press. Her […]

ursa

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA Processes of Transformation “A distinctive characteristic of all cities, and thus also of the urban aesthetic, is the tension that has been, and still is, created between areas and primary elements and between one sector of the city and another. This tension arises from the […]

“A distinctive characteristic of all cities, and thus also of the urban aesthetic, is the tension that has been, and still is, created between areas and primary elements and between one sector of the city and another. This tension arises from the differences between urban artifacts existing in the same place and must be measured not only in terms of space but also of time.”

Aldo Rossi. Processes of Transformation in The Architecture of the City (1966)

If it is true that the palm trees of Porto constitute a distinctive characteristic of the city, and therefore of its urban aesthetic, then, following Rossi’s hypothesis, one is in a good position to look into the history of tensions and processes of transformation that they convey.

The relation between palm trees and Portuguese culture can be traced as far back as 1808, when John VI, then Prince of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves, relocated the court to Brazil fleeing from Napoleonic wars. That same year John VI established the “Royal Nursery” garden – later to become the Botanic Garden of Rio de Janeiro –, where in 1809 he himself planted the first seeds of imperial palm in Brazilian soil, smuggled from Mauritius by Portuguese merchant Luís Vieira e Silva when in transit from the Portuguese State of India, at that point part of the Portuguese Empire.

The dissemination of the imperial palm in Brazil expressed the tensions of class structure in the then overseas colony, just as it later would upon its arrival in mainland Portugal.Own by the royal family and a symbol of Portuguese aristocracy, the first seeds of this “Palma Mater” were seldom offered to selected noblemen for their services to the crown, but mostly burnt to preserve the exclusiveness and the status symbol associated to this species.Naturally such restriction only made the imperial palm more desirable to the eyes of the emerging Brazilian bourgeoisie, which soon gave rise to a black market of the seeds fed by the gardeners of the Royal Nursery.By the mid-nineteenth century the imperial palm was not any longer an exclusive symbol of the aristocracy, but also a symbol of economic power, like a trademark for the coffee barons properties of the Paraíba Valley.

Portuguese cities and, quite notably, Porto, were impacted by the strong wave of Brazilian immigration following the return of John VI and its court to Portugal in 1821 and the subsequent independence process of Brazil.Wealthy Brazilian return migrants settled in the oriental part of the city, away from the center, and undertook the urban expansion towards the east. Their unusually large mansions broke with the standard metric of the Porto plot and defined a new standard of luxury and status in the city.The imperial palms were one of the recognizable symbols of these properties, and just like decades before in Brazil they expressed a new urban and social tension – one related to the upsurge of a new bourgeoisie with a craving for visibility, which would reconfigure urban form and local class structure.

Of course that in time, as palm trees spread across the urban territory and social structure of Porto, the original tension that they carried gave place to that of a collective symbol.Palm trees in Porto traveled across monarchic, republican, autocratic and democratic times. They spread into public space and institutional grounds, were objects of propaganda in the First Colonial Exhibition, and as they were liberalized they were to be found in households of every socioeconomic class, in every neighborhood of the city.Pervasive as they became, standing out and above the cityscape, exotic among the local temperate flora, Porto palm trees shaped the collective memory of the city in the past two hundred years, and in so doing they have acquired historical importance and the unofficial status of monuments.

The arrival of the red palm weevil in Porto circa 2010 has marked the beginning of a notorious process of urban transformation. The pest has attacked a great number of the city palms, and with it disfigured a distinctive attribute of the urban landscape.But as the corruption of these symbols anticipates its disappearance, the very process of putrefaction itself is elevating the monumental character of these elements.The lifeless bodies of dried fibers stand out in their spatial settings like they never did in their lush past, producing a powerful tension of decay that is breaking down the physical evidence of a culture and thus questioning the identity of the city.

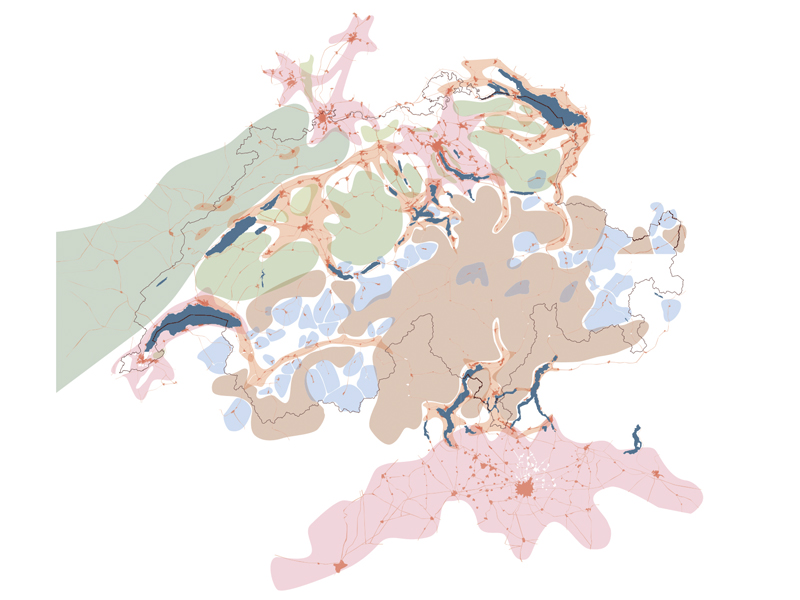

Adrià Carbonell and Roi Salgueiro Barrio

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA Geography and History; the Human Creation “The history of the city is always inseparable from its geography” Rossi, The Architecture of the City, p. 97. Rossi’s interest in geography was not limited to the analytical framework it provides to describe the city. It expresses […]

“The history of the city is always inseparable from its geography”

Rossi, The Architecture of the City, p. 97.

Rossi’s interest in geography was not limited to the analytical framework it provides to describe the city. It expresses a deeper concern about the interrelations between architecture, territory and planning, which is very strongly developed in his writings of the early 1960s. (1) These texts already show a reaction to the modernist “ideology of planning”, to use Tafuri’s terminology, and an interest in articulating an architectural response to it. This response was aimed at fostering the collective and political dimension of space, in the belief that territory and planning were still the conditions that made any architectural project truly operative.

Rossi’s first account of the autonomous dimension that urbanism and architecture can have is aimed at finding a specific role for these disciplines within the mostly economically driven processes of territorial planning. In the collective volume Problemi sullo sviluppo delle aree arretrate published in 1960, Rossi significally starts his contribution with a critique to the totalising meta-geographical approach represented by Le Corbusier for its lack of relation to particular realities. (2) He advocates, instead, for an “elastic planning”, which he defines as “a planning of wide spectrum (referred to an area that constitutes a culturally and geographically unitary nucleus) which understands the project, abandoned of all simplicity, as the articulation of a process open to the diverse requirements, more sensible towards the local historical values, analytic and decentralised” (3). Rossi argues that the autonomy of the architectural and urban discourse introduces, within the strict economic rationality of the plan, the possibility of articulating a political space. Following Carlo Cattaneo’s work, this political space is referred to as a precise territorial realm: “The city forms with its regions an elementary body, this adhesion between the county and the city, constitutes a political persona, permanent and inseparable”. (4)

In Problemi sullo Sviluppo delle Aree Arretrate, Rossi considers that this territorial, political space could be articulated through a new form of settlement: an architectural complex that, joining residence with industry, production with inhabitation, would show the occupation of the region by a new political collectivity. In his subsequent writings, Rossi abandons this functional idea to consider, instead, that commercial and industrial buildings, infrastructures, and the like, constitute the elements that actually organise the territorial scale, while housing becomes an almost negligible element. What remains through this change of uses is the understanding that only architectural fragments can articulate the territory.

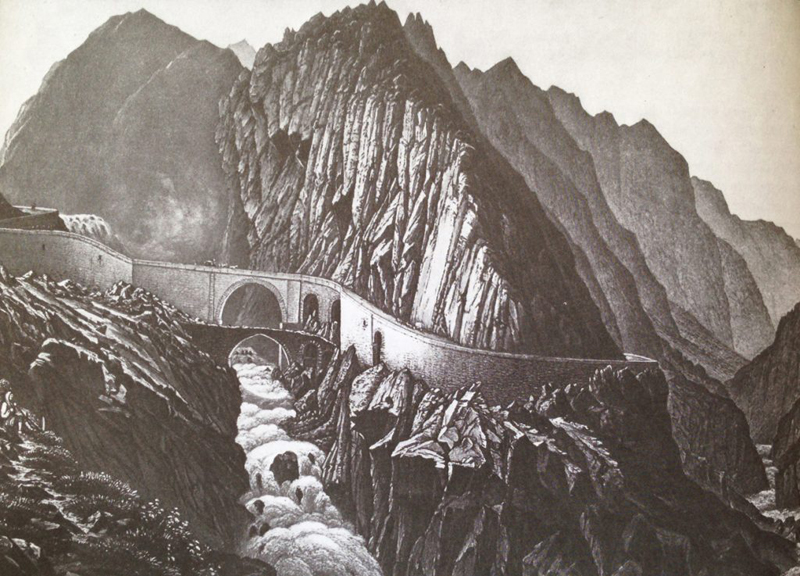

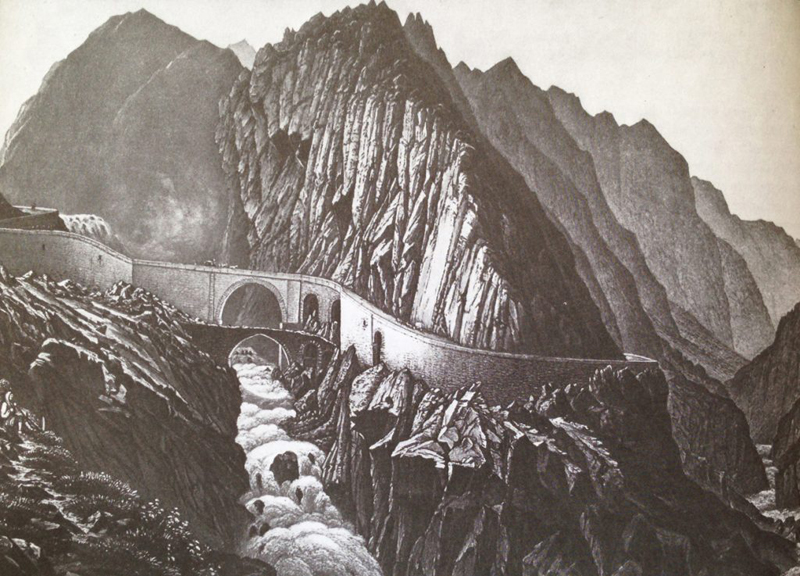

In this sense, the crucial differentiation between primary element and area — where the latter is predominantly residential — that Rossi establishes in The Architecture of the City can be seen as originating not in the city, but in the territory. Even if the notion of primary element, so central in the book, is the element that “characterises a city” and the carrier of its architectural value, it certainly transcends the scale of the architectural object. In Rossi’s words, a primary element “can be seen as an actual urban artefact, identifiable with an event or an architecture that is capable of ‘summarising’ the city”. (5) In a time where the definition of the urban has come into crisis, when extended urbanisation processes have taken a planetary dimension, more than looking at the city as a traditionally bounded, compact, and distinct formal structure, it may be pertinent to look back at the intertwined relations between architecture and geography, or in other words, at the construction of the territory as a “Human Creation”, with all its cultural, political and geographical dimensions. The city Rossi was trying to encapsulate in his theory was composed of a varied, complex and rich architectural imagery, reaching beyond the historic and modern repertoire of formal articulations. By broadening its classical definition, we may conclude that the form of the city is to be associated with its geography, its routes, highways and other infrastructures, the irrigation of fields and industrial settlements; thus, the form of the city would actually be the form of its territory. In this sense, Rossi participates of a generational concern, yet, unlike some of his contemporaries — like Saverio Muratori or Vittorio Gregotti who investigated how geography could contaminate architectural and urban form — the a priori formal autonomy of architecture that Rossi claims has the capacity to determine how the territory is going to be perceived and how it is going to be culturally and politically articulated. This may be one of the lessons we owe to Rossi’s The Architecture of the City, a book about the city that opens with the image of a bridge in the territory.