Pre-Architect

There was a time when the urban planner or architect was a public figure. He or she would have been the expert mandarin of a technocratic society, the public intellectual, the celebrated artist, or the popular leader of a participatory movement. The erosion of these public positions has produced a slumbering malaise within the discipline. But more importantly, it points to a general incapacity to engage coherently in the public sphere, in the legitimation of public actions.1

Some months ago, on the occasion of a study trip to Berlin, I visited the BigYard, a recently built half-block residential complex in the historic neighborhood of Prenzlauer Berg, in Berlin. Our host was Sascha Zander, resident at the Bigyard and architect co-founder at Zanderroth Architekten, the office responsible for this co-housing project.

Zander and Roth initiated their practice by the end of the 1990’s decided to choose the projects they would like to build. Since then, they have developed an effective building model according to which they became able to generate their own architecture design commissions. While leveraging on the popular co-housing schemes of Baugruppen, the architects subtracted the developer from the building equation, not only to provide more affordable houses, but also to reclaim back the responsibility for defining the urban and social impacts of their projects within the city.2 Self-initiative took them to consider additional tasks concerning the classical practice of architecture, while starting to deal with the factors that precede it, i.e. that make architecture possible in the first place.3 Philipp Oswalt coined this modus operandi as ‘Pre-architecture’.

- A tour around the BigYard

At Zelterstrasse, the sober playfulness of the 100m-length paneled façade distinguishes the new building from the surrounding five-story homogeneous blocks of Prenzlauer Berg centennial borough, in a sheer respectful manner. From the street, what intuitively looks to be an apartment building, with flats stacked on each other, reveals to be a row of four-story townhouses disguised by a unifying façade. This volume is only breached by a pedestrian covered passage, which provides access to the backyard. An oblong courtyard garden mediates between the longitudinal street volume with 23 townhouses, and a parallel one in the back with 22 housing units. Here, three-story penthouses, with direct access to the communal roof terrace, are stacked on top of three-story garden houses, a step away from the courtyard garden. In total, 135 people dwell in the BigYard, Four of the 45 units are shared, and intended to host guests.

On the way to visit the communal roof terrace, we are not allowed to cross the courtyard, as agreed between residents, given the early hour. In this regard, Sascha elaborates on the dörflichen character of the project and refers to the founding principle of providing an atmosphere similar to a village, where high density of occupation intersects with the desire for an individual house, under the condition of a permanently negotiated close proximity.

This project addresses the wishes of middle-class families earning average incomes – ‘separate dwellings, large garden, green roof, open outlook, front door onto the street, parking behind the house’ 4 –, which didn’t have the chance to gain access to the housing market and become homeowners within the inner city. According to the architect, the goal was to offer a lifestyle that combined the urban and suburban condition in a central location: ‘the project expands our ideas about contemporary urban housing. Housing is no longer confined to simply providing accommodation for people. It has more to do with the spatial organization of leisure time spent at home. Housing should contribute to recreation.’4

Sascha describes the building model process that allowed them to set up this residential complex from its first spark, tracing the most significant tasks carried out, as well as their phasing, for a period of four years, between 2006 and 2010. With approximately 9.000 m2 of total floor area, this project represents a total investment of 15 million euros.

According to the architect, it all started with the choice of the plot to intervene and the search for its owner, with whom they signed a one-year ‘option to buy’ contract, assuming themselves the initial risk. In order to gain time to develop the project, as well as to complete the organization of the Baugruppe, this figure fits well one of the main challenges of their model: the need for a long organizational lead-time. / With a clear concept in mind regarding the usages and their target audience, during the first months they developed the concept design and the submission project, in order to get official approval. Still without any client, architects took the economical risk. / Once the project was officially approved, architects launched an advertising campaign for selling the housing units at ‘SmartHoming’ website5, the ‘sister’ company of Zanderroth Architekten, which dedicates to marketing, project management and client care. A brochure with all the necessary information for purchasing an apartment – location, list of the different available flats’ typologies, floorplans, areas quantities, visualizations, prices – was made available to the public. The aim was to find clients – and future users – to participate in BigYard Baugruppe. / The Baugruppe grew gradually upon applications, under the legal framework of a civil law association. Members signed a partnership agreement – GbR (Gesellschaft bürgerlichen Rechts) – that outlined who was to obtain which apartment and which share of the total cost it represented. From this point, the clients’ collective shared all the financial risks, and the liability of each member was proportional to the respective share of ownership. Likewise, all the decisions represented a consensus between all the members of the group. / As soon as the required capital for construction was gathered from members’ funds, the Baugruppe acquired the plot and Zanderroth Architekten proceeded with the construction project.

From this moment onwards, the architects organized monthly group meetings with the members of the Baugruppe both to report about the progress of the project, and to collect participants’ points of view. One-to-one meetings between the architect and each one of the clients also took place during the final stage of the construction project, in order to fine-tune aspects related to the organization of domestic spaces and to define interior coatings, pavements and furniture materials in each apartment. / The construction would take approximately two years, evolving efficiently under architects’ control. By assuming construction management, architects managed to cut time and costs in the process. / Once built, keys were delivered to the house owners. The architects also became residents.

With the development and maturation of this Baugruppe building model, Zanderroth Architekten managed to develop and consistently implement multiple co-housing projects within Berlin’s inner districts for the last ten years.

- Baugruppen and the Self-made City6

Zander and Roth started their practice by elaborating a catalogue of empty plots in Berlin, and found more than 1000. After selecting a few, they researched about their ownership and dedicated to persuade landowners with their ideas for these sites. This pro-active and entrepreneurial attitude earned them their first commission.

Indeed, Berlin is labeled a ‘Self-made city’. Self-initiated projects became a mainstream phenomenon within the last 15 years, providing paradigmatic cases of architecture and urban development, particularly concerning housing.

This singularity is rooted in Berlin’s squatter movements ‘tradition’, born in the 1980’s, when artists and activists broke in, took control and made livable vacant buildings in Kreuzberg neighborhood, after the cancellation of government’s ambitious plans for a new highway that would tear apart that neighborhood. In 1987, IBA Altbau would tap into the do-it-yourself energy of the squatter movement by fixing these old buildings, then handing them over to their residents as rightful owners. After the fall of the Wall in 1989, social housing (government subsidized, rent-controlled, pre-fabricated concrete housing) made up most of the housing all over Berlin. In turn, the old center of East Berlin was a no-man’s land, with over 25.000 apartments unoccupied. A strong associative and self-made culture developed in the early 1990’s among people occupying these rundown buildings. Self-initiated projects in the form of clandestine bars, clubs, galleries, shops, cultural institutions, meeting and working places were countless. On the other hand, the focus of development in the city after political reunification in 1990 would turn East, and profit-oriented investments focusing the renovation of these buildings had a disruptive impact over these associations. Despite this, between 1984 and 2003, the governmental program Bauliche Selbsthilfe (in English, Self-Help Building) enabled over 300 squatted buildings and self-organized housing projects to be legalized through private self-initiative. Indeed, Berlin’s transformation years were the foundation for do-it-yourself project makers.

In 2002, German’s economic recession took the State to cut funding for housing programs and investors stop building housing. Berlin’s urban fabric was left with numerous empty building sites. These small ‘holes’ presented the very special potential of Berlin and were the catalysts for a new type of development in the inner city7.

At this stage, affordable living spaces in the city became limited, and the economic pressure on residents and users had risen dramatically. Nevertheless, families wanted to stay in the city and people show interest in owning their apartment; both to ensure a stable cost of living and to dwell in more personalized living spaces. Basing upon this generalized desire, Zanderroth Architekten starts to develop architecture projects themselves, carrying out designs to fill the existing ‘holes’ in the urban fabric.

The formation of Baugruppen (in English, builders group, building collective, client collective) is the framework condition that enables them to substantiate these enterprises. These are the outcome of a specific legal and cultural context, and constitute a condition sine qua non for the necessary generation of usages, clients and funding, which enables the materialization of the architecture project.

Zanderroth initiate their first Baugruppe in 2005, forming a small group of clients with whom they propose to share the responsibility of design. While demonstrating alternative solutions, it is the possibility that architects deploy for people to take charge of determining their own living environment that reveals a valuable resource in urban development, created in the area of tension between freedom and need7.

III. Production of desire

The success of Zanderroth Architekten approach is related both with the affordability and the flexibility of their residential units. Middle-class people earning average incomes become able to become homeowners within the inner city. Besides, the opportunity to get individually tailored living space adds inestimable value to the investment of a lifetime.

After understanding that the developers earned a 20% average profit in each project – difference between production costs and sales price – Zander and Roth decided to determine their own framework. According to this building model, there would be no developer to assume the risk and make a profit thereby. Instead, the coordinated design and construction processes enabled them to finance additional spatial qualities through reducing production costs. Cost-effective projects are obtained as there are less people involved, and timesaving decisions are taken along a centralized and optimized construction process. When comparing to the prices provided by real-estate market, the final cost per square meter is far below the market average.

Furthermore, their cunning ploy is also founded on the discovery of less valuable plots, according to real-estate investors’ perspective. The conscious choice for a ‘difficult’ site is one of their trump cards: within a cheaper plot they manage to create assets that add value both to the site, to the new buildings, and ultimately to its surroundings. Architects consider themselves to be responsible, together with their clients, to do a meaningful design for the housing units and the building, but also for the urban space, emphasizing the importance of the interface between public and private.

Through an urban-oriented architectural design that goes beyond investor’s urgency to create built financial assets, Zanderroth put to practice the capability to transform a disadvantage into an advantage. Their first project for RUSC Baugruppe illustrates well this aspect.8 At the north-oriented corner site between Schönholzerstrasse and Ruppiner Strasse, the architects created a public square within private property, completely open to the neighborhood, and the Baugruppe assumed to take care of it for the next one hundred years.The constraint typical of a Berlin block corner, where light doesn’t reach adequately most of its compartments, was faced as an opportunity to enhance the urban character of this intervention, and deployed an ‘untypical’ solution. It resulted in the separation of the program in two buildings, with apartments facing three sides – towards the street, the new square and the backyard. Architects and clients’ collective took on responsibilities that reached beyond their own property and buildings, creating new possibilities in the neighborhood and encouraging interaction with the surrounding urban environment.

Another pillar of this building model is the ‘design deal’ arranged between the architects and their Baugruppen members. Architects state a priori that clients are to keep what would be the profit margin of the developer; in exchange, they demand total freedom for each project’s design, except for the domestic interior spaces, as mentioned before in the case of BigYard.

Concerning the design of the housing units, Zanderroth effort is put into optimizing spatial organization regarding maximum economy and flexibility of space, as well as into interpreting the spatial requirements of a specific target audience. In BigYard project for example, a project thought out to house young families with children and an average income, architects define the spacious kitchen as the living core of the house, with a 4.20 m height that allows it to have visual contact with two floors, and a balcony towards the backyard. On the other hand, housing units are generally provided with smaller areas than the ones delivered by real-estate market, simultaneously allowing for a certain number of adjustments regarding the compartmentalization of the unit – the number of bedrooms for example. Through the design of ‘untypical’ and, nevertheless, smart typologies, architects manage to produce densely occupied projects, thus generating more affordable housing units.

On an urban scale, projects carried out by Baugruppen are gradually growing in size due both to the recent scarcity of small infill plots and to the unification of different collectives with compatible wishes regarding the conceptualization of public space. The challenges featured by these new urban interventions bring an added complexity to Baugruppen processes. Nevertheless, these also reveal new potentials for architects to explore while shaping pieces of the city.9

A project of such scale exposes, first of all, the necessity for admitting other programmatic usages in the project, in order to offer adequate urban living conditions. Finding the mechanisms to integrate infrastructural facilities like supermarkets, schools or day care centers, is one of the challenges with which the architects are currently dealing with. According to the architects, the hypothesis is to call companies or institutions to become part of Baugruppen from the beginning, in order to enable for integrated solutions. This integration may admit, for example, cases of ‘cross-subsidizing’, according to which profit-oriented supermarket chains are brought on board only if contributing for lowering housing unit’s prices.4

Commenting on their recent project in Friedrichshain borough, within a plot with 8.000 m2, the architects identify also their aim to widen the socioeconomic range of people that can afford to join Baugruppen. Leveraging on a more substantial critical mass, they managed to offer a wider range of prices for the apartments by diversifying units’ sizes and relating these with its vertical position in the building – size plus height equals price. This redistribution strategy allowed them to offer penthouses with a price per square meter that is almost the double of the price they offer for other apartments within the same building project. On the other hand, they have also foreseen the option for merging and separating two adjacent apartments, arguing for the evolution of needs of the tenants over the course of their lives, and the possibility for enabling rentals. They conclude: ‘Nevertheless, it would be naïve to believe that, like some kind of Robin Hood for the housing market, we could ever compensate for the major political failures that exist in Berlin due to the complete lack of a socially sustainable housing policy.’4

- The public role of the architect

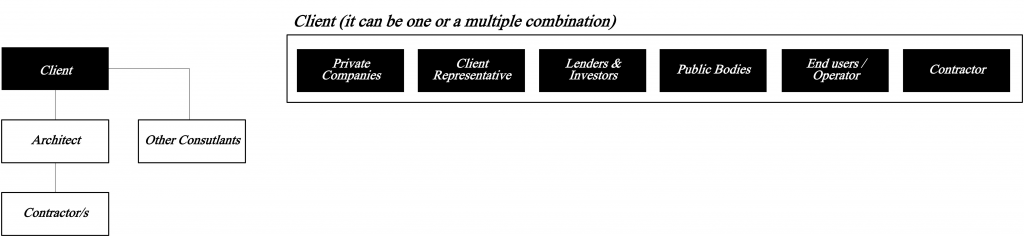

While initiators of their own projects for co-housing buildings, Zanderroth Architekten assumes and conciliates multifarious pre-architectural tasks – land procurement, expertise in law, financial modeling, market analysis, marketing, Baugruppen mediation and client care – besides the architecture design proper of a ‘classical’ practice of architecture, as we know it from school. Nonetheless, and despite not revealing an unprecedented building model, both their discourse and designs seem to propose a ‘fresh approach’ within the architecture debate, arguing on the possibility for architects to play a public role.

In fact, there are multiple examples of architecture practices that integrate services and optimize building processes, in order to deliver cheaper turnkey projects. This is usually the case with market-oriented strategies, which have underlying profit margins, and where users are not part of the building ‘equation’.

On the other hand, housing cooperatives are also a pertinent figure for drawing a parallel with Baugruppen. Often created to provide affordable housing, their relevance is much related with the absence in the first place of the mentality of private property ownership, thus avoiding any motivation for real-estate speculation. According to Zander and Roth, reality shows nonetheless that a newly founded cooperative is not as financially powerful as a building group, as it must raise the entire budget for the building project from scratch.4 Moreover, the current European economical context is revealing to be arid ground, since States’ effort gradually abandoned these social mechanisms, instead facilitating the life of housing corporations and stimulating the real-estate market, thought as catalysts for ‘urgent’ economical growth.

On this purpose, it is worth to mention a particular case: the Fideicomiso, a legal framework that resurged in Argentina after national banking crisis in 2001, enabling local architects to initiate their own building models.10 According to this figure, architects and clients sign a kind of fiduciary contract based on trust that allows the architect to take on the risk of a development, using the residents collective assets to buy the land, fund the project and deliver the scheme. Like with Baugruppen, this scheme draws clients to participate along the design process and the final price of the apartments is thought to be 20-30 percent cheaper than on the open market. Yet, and despite having contributed during the last ten years to the revitalization and densification of low-valued neighborhoods across Buenos Aires, Fideicomiso projects have few arguments to produce any significant impact within a broader societal context, given their small scale.

In turn, Zanderroth Architekten building model reveals new faculties that instill added values to the design project. Catalyzing on the strength of Baugruppen – culturally assimilated and legally matured within Berlin’s context –, their practice distinguishes for channeling this ability to deal with the generation of usages, clients and funding, towards the production of a critical intervention in the city. In order to produce an effective impact by reaching beyond plot boundaries, this model either challenges or engages with the societal status quo, ultimately through design. That is what Pre-Architects do: they put forward a social agenda.

Regarding the ‘classical’ architectural practice, the Pre-Architect displays a reaction to the ‘self-amputation’ to which Postmodernism had condemned the professional field of architecture, since the 1960’s and 1970’s. Criticism of technocracy, rationalism, and utopianism led architecture back to its own discipline, this way screening out questions that were to go beyond it, allegedly undermining architecture. The increasing reduction of architectural discourse to questions of form blocked out the question of how architecture could be created in the first place. But the architectonic design can gain relevance only if it answers the question of how it can be created.

The proposal of this new professional figure is to go beyond the narrower field of architecture, i.e. the architect as the exclusive artistic genius serving a private client, and turn to pre-architectural themes, as an inclusive engaged architect that plays a public role. While leading to the re-politicization of the architectural debate – Who builds with which resources and to what end? 3 –, the advent of the Pre-Architect testifies to the democratization of architecture.

In this regard, and against the background of the persistent image of the master-architect, it might reveal pertinent to draw attention to the multifarious relations between the architect and the public on postwar context, as systematized by Avermaete.11 Either the syndicalist – who questioned the social status quo -, the populist – who challenged professional conventions -, the activist – who fought for spatial justice by transgressing the action boundaries of the profession -, or the facilitator – who engaged inhabitants to realize an ambitious project –, they all have intervened within society by dealing with pre-architectural tasks, this way contributing for empowering the people.

In fact, the political load of architecture manifests today once again, this time reacting to the backlash of neo-liberal times and its disruptive effect on the urban condition. Therefore, the Pre-Architect is, once again, called to develop the skills that allow him to engage coherently in the public sphere and in the legitimation of public actions. The Pre-Architect is a public figure.

Bernardo Menezes Falcão is a Portuguese architect. He holds a postgraduate Diploma on Sustainable Cities and has completed the Master of Advanced Studies in Urban Design at ETH Zurich as a scholar of Geisendorf Foundation. His project ‘Inside-Out’ for the informal settlements of Cairo – developed in collaboration with Grigorios Dimitriadis and Shinji Terada – was exhibited in the 2015 Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture in Shenzhen and Hong Kong, and in the Egypt Urban Forum, organized by UN Habitat in Cairo. As a practitioner since 2007, he collaborated with urban planning and architecture offices in Lisbon, Zurich and Rotterdam.