Classifying the Déclassé: A Non-Methodical Methodology

Dr Annebella Pollen

Dewey Decimal schemes, archival fonds and sub-fonds. Acid-free boxes, Secol sleeves and white cotton gloves. As a historian of material culture, working with texts, images, artefacts and collections, my practice may seem to be formally organised and performed via recognisable systems. It is underpinned by scientific coordinates, disciplinary apparatus and proprietary products. These are the […]

Dewey Decimal schemes, archival fonds and sub-fonds. Acid-free boxes, Secol sleeves and white cotton gloves. As a historian of material culture, working with texts, images, artefacts and collections, my practice may seem to be formally organised and performed via recognisable systems. It is underpinned by scientific coordinates, disciplinary apparatus and proprietary products. These are the tangible tools with which I work; my visible structures, if you like. Neon Post-It notes and highlighter pens make the see-able and know-able world even more hi-vis.

How ordered it all sounds! I train my PhD students in how to organise their data, code their interpretations and structure their chapters. I evaluate research proposals on their logical design and developing arguments against specified criteria. I earn my academic keep by balancing budgets and populating spreadsheets. Yet my office is a mess. I learned recently that there are two types of hoarding, horizontal and vertical: piles on the floor and piles up the walls. I’m giving them both a try. I variously group my books by colour; into themes according to what I’m working on; by their proximity to my desk; by how much I can bear to look at them or not look at them. I’ve discovered that this kind of emotionally reactive and mostly productive non-method has a nickname: procrastivation. It avoids the centre by working at the margins.

The subjective selections that underpin classification structures fascinate me and I’ve long been attracted to research material that eludes easy categorisation. Photographs, for example, seem to offer a straightforward window on the world but they are constantly disruptive of the boxes into which they are placed. They slip between truth and lies, science and art, documents and pictures. They are never simple illustrations of the visible and there are far too many of them to know where to stop. Their excess, in terms of what they picture and their quantities, is a key characteristic. Their captions and their storage and display locations tether them to a certain extent but they always exceed their parameters. Their character is complex and their meanings are ever multiple.

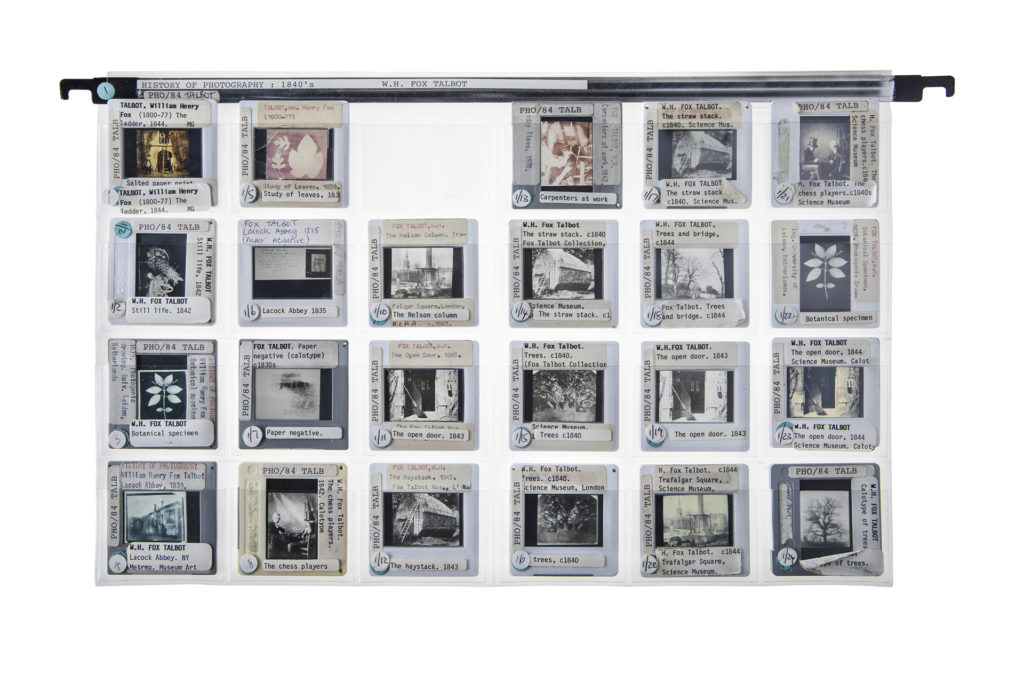

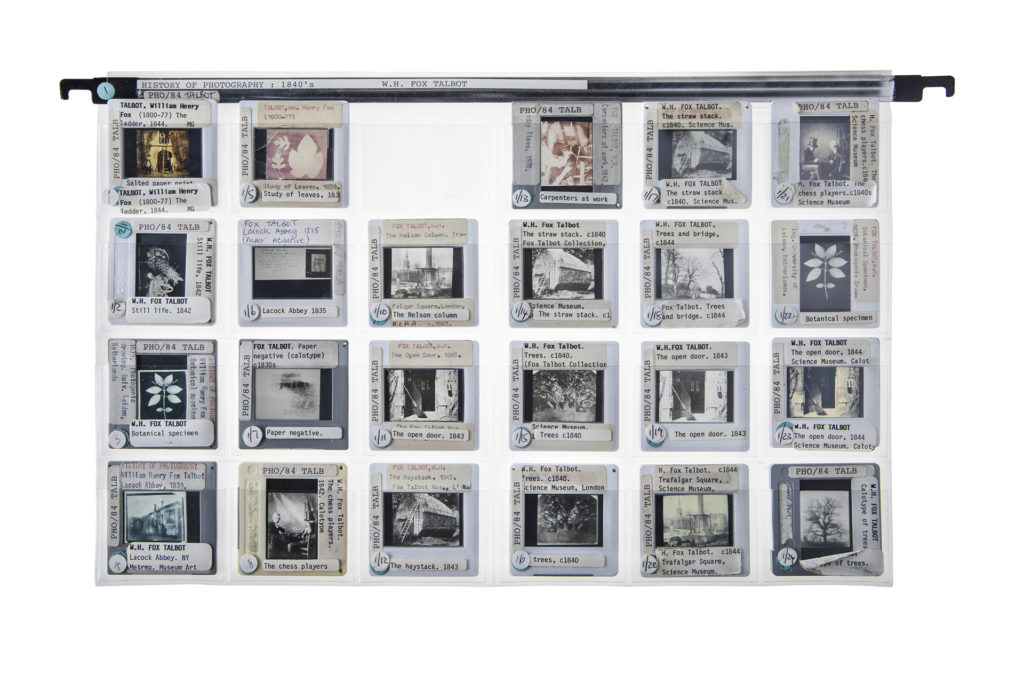

Sample hanging file. Former History of Photography collection, University of Brighton slide library.

Photograph by Richard Boll, 2019.

The second-hand marketplace is another site where objects’ relative fortunes are made and unmade, where treasure and trash are bargained over, where narrative and context variously adds and subtracts cultural value. The dealers at dawn haggling for house clearance cast-offs may or may not have read Pierre Bourdieu’s famous 1960s study, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, but they live it out daily as they move goods from unwanted to wanted and rate them accordingly. A sign at the door of a local flea market frames these shifts playfully: We buy junk and sell antiques. Pricing seems to add objectivity but the rules are mostly unwritten and get renegotiated with each transaction. Taste classifies, and it classifies the classifier, as Bourdieu famously put it. We are what we value; we are what we throw away.

These subjective selections and mutable taxonomies are the subject of my research as well as the operating systems through which I receive and interpret my information. Most of my projects concern what I call non-canonical material: the overlooked, troublesome and unwanted. I relish the challenge of the wild things, the unwieldy. I’ve cherished orphaned family albums, unsaleable garments at the dump, photo competition rejects, deaccessioned museum collections and archival boxes marked ‘Miscellaneous’. These are difficult objects that create disorder and that reveal the inadequacies of the systems that are meant to provide meaning and certainty.

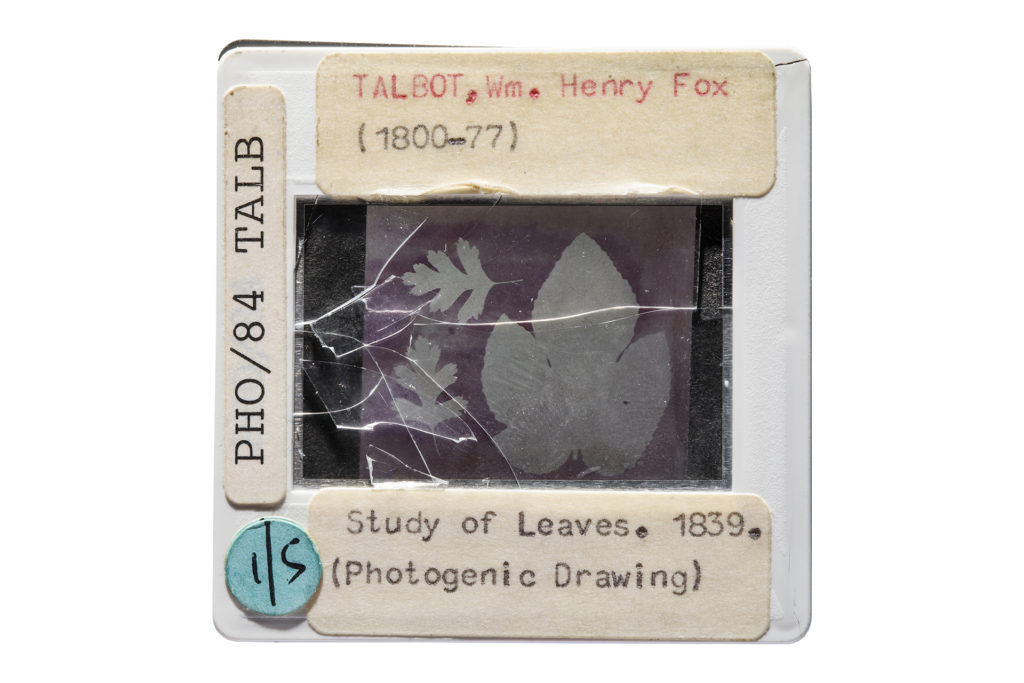

Broken slide. William Henry Fox Talbot, Study of Leaves, 1839. Former History of Photography

collection, University of Brighton slide library.

Photograph by Richard Boll, 2019.

A pertinent example of such a project is the study I have made of art school slide libraries or, rather, their destruction. Once the core site of the visual aids through which histories of art and design were taught, the 35mm slides and their analogue projection equipment have recently been deemed obsolete. Tiny, carefully-labelled squares of glass have been superseded by vast virtual image databases and speedy digital display mechanisms. The labour of generations of slide librarians in photographing, mounting and processing the hardware of visual information has been decimated, in some cases literally ground to dust, over the past decade or so. In my institution, as with many others, hundreds of thousands of images were dismantled and dispersed. Artists and art historians, however, sentimentally rescued what they could. To me, they contained the historiography of a discipline and its technology; its archaeology of knowledge, to borrow a phrase from Foucault.

Two filing cabinets in my office are stuffed with my university’s former history of photography collection. Some slides are shattered, faded to pink; others stick to their decomposing storage systems. They speak of order and chaos, the enduring and the fragile, the changing materiality of photography and its ever proliferating scale. Slides of the very earliest of photographs from the 1830s, taken and displayed with 1960s technology now abandoned, seem hopelessly poetic. I was taught my subject via these transparencies when I looked through them as images rather than at them as objects. I now see them as structures, as indexes of cultural flux. Their fallibilities are writ large in their bulky forms, their peeling stickers, handwritten labels and yellowing cases. They seem clunky and clumsy in a friction-free world of easy image supply. Their slowness and messiness, however, reveal complexities and show how the visual world is ordered and disordered.

How to manage the unmanageable? How to tie this turmoil down into a visible and readable outcome? Words, my other tools, share a mercurial character with my research materials; they are similarly slippery and similarly spatial. They pile up and spill over. I scribble them on scraps and pour them onto screens. I do it in the middle of the night or when the mood takes me, on a run or at the kitchen sink. I scroll up and down Word documents and iPhone photo feeds, adding hearts and asterisks. I circle, underline, fire arrows and shout capitals and until patterns emerge at the edges. I need to keep rummaging through the clutter, the overflowing folders and the teetering towers of boxes. The disorder is essential and the process is never truly structureless. Perhaps my methodology comes closest in practice to Walter Benjamin’s ragpicker, in turn borrowed from the nineteenth century poetry of Charles Baudelaire. I assemble wholes from individually unpromising parts. I rehabilitate rubbish.

Dr Annebella Pollen is Reader in History of Art and Design at University of Brighton, UK. Her research interests include popular image culture, especially in relation to the uses and expectations made of photography. Publications include Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life (2015) and Photography Reframed: New Visions in Contemporary Photographic Culture (2018, co-edited with Ben Burbridge). Her other books include Dress History: New Directions in Theory and Practice (2015, co-edited with Charlotte Nicklas), The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift: Intellectual Barbarians (2015), a visual history of a utopian interwar youth group, and the forthcoming Art without Frontiers, on British art in international cultural relations.