Phineas Harper

“There are no limits to growth and human progress when men and women are free to follow their dreams,” lied Ronald Reagan in his re-election inaugural address in 1985. Only a decade earlier, the Club of Rome had prophetically warned that, if the physical limits to growth are ignored, society will ‘overshoot those limits, and […]

“There are no limits to growth and human progress when men and women are free to follow their dreams,” lied Ronald Reagan in his re-election inaugural address in 1985. Only a decade earlier, the Club of Rome had prophetically warned that, if the physical limits to growth are ignored, society will ‘overshoot those limits, and collapse.’ But the promise of perpetual progress – life without limits – was a powerful propaganda message for Reagan’s doctrine of deregulation.

Today, endless progress by overcoming limits is still celebrated through cringeworthy clichés: ‘Know no limits;’ ‘you are your only limit’ or ‘don’t tell me the sky is the limit when there are footprints on the moon.’ Even as unprecedented fires, floods and biodiversity loss reveal the extent to which the cause of progress has pushed the planet to breaking point, our relationship with limits remains antagonistic. It is no coincidence that within Labour, Europe’s largest political party, the faction least prepared to use parliamentary power to take bold action on confronting climate change is named ‘Progress’. Is it time to turn away from the mantra of progress?

In the opening of his seminal manifesto, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth the American architect Richard Buckminster Fuller argued that, shipwrecked in a storm, you might avoid a watery grave if by chance the top of a mahogany grand piano came floating past. Clambering aboard this improvised raft, you could cheat death, but your miraculous escape would not mean that the best design for a life jacket is a piano top, nor that ships should ensure the safety of their passengers by stocking an abundance of Steinbergs.

Bucky’s point was that just because something gets you through in a moment when your options are limited, that does automatically not make it the best designed tool for the job in the long term. Yet as a culture we are clinging to all manner of piano tops – systems, practices and materials that allow society to stumble along despite being evidently unfit for purpose and increasingly unable to weather the turbulent waters ahead.

“If we invented concrete today, nobody would think it was a good idea,” argued Michael Ramage, head of the Centre For Natural Material Innovation at the Architecture of Emergency summit in London.1 “It’s liquid, needs special trucks, takes two weeks to get hard and doesn’t even work if you don’t put steel in it. Who would do that? — Nobody!” We have built up such a vast infrastructure around manufacturing concrete that despite its deep flaws, it seems impossible to shake its ubiquity in construction. The predominance of concrete is just one of the many ways in which the piano tops of yesterday shape the possibilities of tomorrow.

Like concrete, I believe the love of progress is a piano top – an addiction we uncritically cling to knowing the harm it can cause for fear of finding an alternative. Progress, like growth, is so intertwined with our conception of prosperity that it is hard to even find the vocabulary with which to describe a good life without them. What would architecture be like without this socialised obsession? What kind of buildings would a culture at ease with its own limits commission? What materials would we specify if architecture was no longer made in the service of endless progress, but of maintaining equilibrium?

Many architects have a pathological fear of maintenance. When work is done on buildings that does not result in bigger better features it is generally considered a failure of the designers to not use more resilient materials. Specifications are regularly made with the sole intention of reducing maintenance needs – green spaces are paved, vinyl is laid over timber floors, tarmac is poured on cobbles, etc. To actively embrace maintenance, rather than avoid it, would mean a sea change in the material culture of construction, and a revaluation of janitorial labour. Thatching, for example, was once a widespread roofing technique with good thermal performance, hyper-low environmental impact and seductive sculptural qualities. Yet today, thatch is not just rarely specified, but actively replaced as its need for occasional repair makes it unattractive in the eyes of our durability-obsessed culture. What would it mean to rethink this stance, to embrace thatch, and other plant-based and natural materials with vigour, not despite their need for maintenance, but because of it?

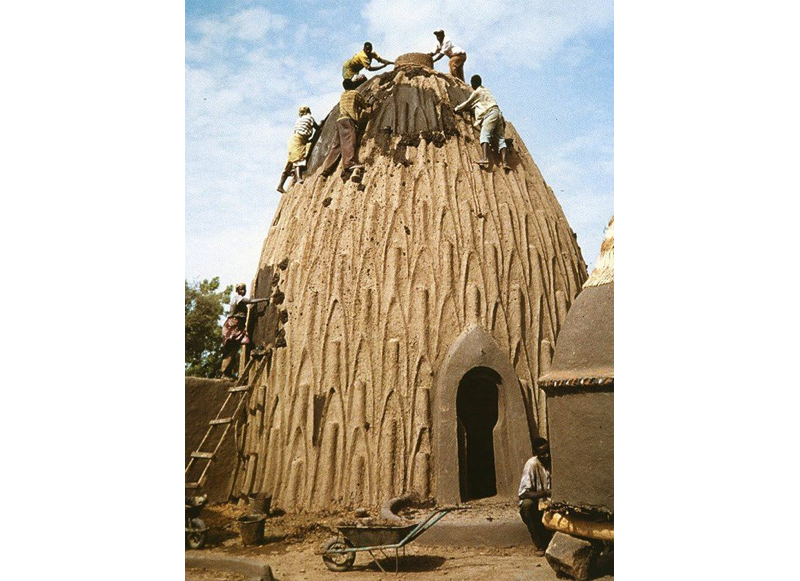

The architecture of the Musgum people in Cameroon features tall domed mud huts, their facades covered in geometric arrays like the texture of a Peter Randall- Page sculpture. However this pine cone-like pattern is not simply a decoration, the deep relief of nooks provides the hand and foot holds for labourers to clamber over the facade, repairing the mud render throughout the year. For the Musgum, facade repair is like window cleaning – something that should be regularly repeated and which good architecture facilitates. What would it mean to apply such a philosophy to contemporary western cities so that acts of repair are valued and expressed formally?

Maintainance of a Tolek — a Musgum earth house

There is, perhaps, a lesson to draw from high-tech. The glass facades specified in gleaming towers across the world by the likes of Norman Foster and Richard Rogers don’t need repairing often but they do require regular cleaning. In the hands of the best high-tech architects, window cleaning infrastructure became exuberant architectural features such as the deep blue cranes perched on the Lloyds Building by Richard Rogers2. If high-tech can articulate cleaning as architecture, what new forms and architectural devices could embody an architecture of maintenance?

Lloyd’s Insurance Building, Richard Rogers, London, 1986

The urge to always progress – for growth even beyond the natural limits of our planet and climate – is driving architecture and society to make wildly unsustainable choices. The lure of progress has accomplished some great things, but it is increasingly clear that we must establish a more critical relationship with the purpose and pitfalls of progress. Westen architects must unlearn their colonial mindset of constant expansionism and learn instead from indigeinous communities whose architecture facilitates ongoing care, rather than ongoing growth. The architect of tomorrow will no longer be a servant of progress but an agent of equilibrium – reconfiguring of form and matter in a constant process of adjustment and replenishment promoting balance. Architecture as an endless process seeking the end of endless progress.