Acceptance as progress

Sara Davin Omar and Felicia Narumi Liang

“It is true that development is not always the same as improvement, and we do not know whether horsepower is better or worse for human life and happiness than the horse. But building-art, like applied art, cannot decide such questions; it is a servant that has to accept the prevailing culture and base what it […]

“It is true that development is not always the same as improvement, and we do not know whether horsepower is better or worse for human life and happiness than the horse. But building-art, like applied art, cannot decide such questions; it is a servant that has to accept the prevailing culture and base what it does on it”.1

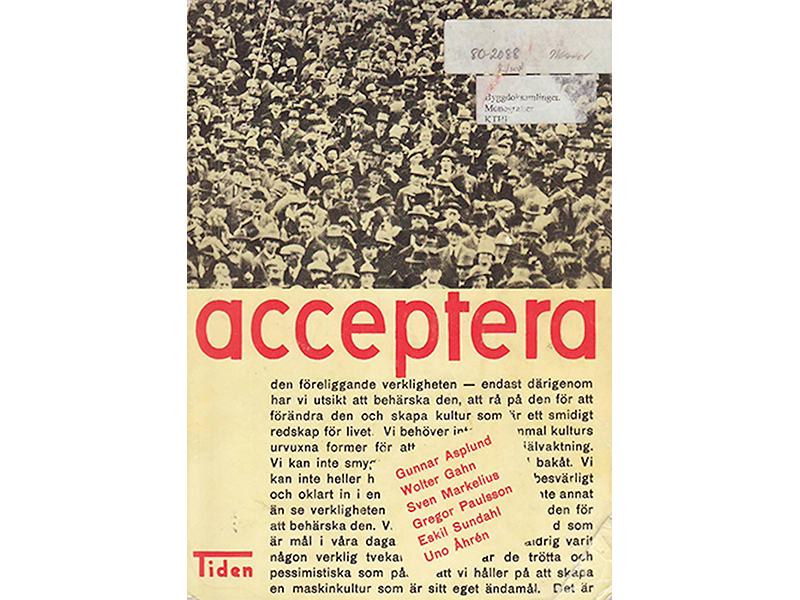

In 1931, a manifesto was published in Sweden that seemed to promote new polemic ideas. Modernism as a movement was hereby introduced with acceptera(accept!), a product co-written by prominent Swedish architects at the time: Gunnar Asplund, Wolter Gahn, Sven Markelius, Gregor Paulsson, Eskil Sundahl and Uno Åhren. Unlike Le Corbusier´s Toward an Architecture (1923) who recognized architecture as a biopolitical tool that could prevent revolution2, and Ernst May’s housing project Das Neue Frankfurt (1925 -1930) whose modernity was an attempt at a “concrete politicizing” of architecture through the Social-Democratic model3; the authors of acceptera seemed to imply a much less political view on architecture. Instead, they propose the shift from neoclassical to modern architecture simply since it represented the spirit of the time.

“Accept the given reality – only thus may we have a view to control it, to master it in order to change it and create a culture which is a flexible tool for life.”4 The text is formulated as an imperative, ordering Swedish architects and designers to dare to take the step towards the inescapable spirit of the age: between the modern and industrialized “Europe A” versus the retrogressive and rural “Europe B”, lying 150 years behind its opposite model5. The manifesto seemed to introduce completely new ideas for the Swedish audience, but when looking at the modern interventions accentuated in the text – numerous of these had already been implemented in Sweden during the 1920s. For example, the important cooperative association HSB were already applying simple and effective plans, prefabrication of carpentry details and increased hygienic standards.6

One year before the publication of the manifesto, the national fair Stockholmsutställningen(the Stockholm Exhibition) introduced modernism for the masses of 4 million visitors.7 The exhibition featured contributions that seemed to harness modernism and optimism and even if most of the structures were all demolished afterwards, the event has been considered a symbol of how Sweden officially entered modernity and rebranded itself as a “modern” and “progressive” nation. Curated by Gunnar Asplund along with other participating architects such as Uno Åhrén and Sven Markelius, the exhibition was to a large extent dedicated to show elements that would make up an important part in the ongoing project of the welfare state, initiated by the national Social Democratic party. Models for rented apartments, townhouses and cooperative supermarkets were displayed, some of them rejected by critics as “a row of chicken coops and rabbit hutches”8. Nevertheless, it was in conjunction with this newly established self-identification of a modern society that the architects behind the exhibition could declare the architectural manifesto and all-embracing statement of how the life of modernity could be achieved in Sweden with acceptera. Even though Stockholmsutställningen displayed a built environment strongly in unison with the ideals of the Swedish welfare state, the manifesto of 1931 does not show an approach that actively defends the ruling political ideology of the time, social democracy, against its countering ideologies.

Despite the positivity regarding the spirit of the time with the modern aestheticism attained through mass-production, acceptance as strategy can also imply a somewhat indifferent attitude towards the surrounding political and cultural environment. Admitting that the consequences of the modern lifestyle and its innovative techniques were not necessarily more positive through the example of the horse and horsepower, the group still seemed to argue that it is the underwriting of the status quo; seemingly no matter what it may be, which will enhance the progress in the realm of architecture and design.

When arguing for a de-politicization of the modern project in comparison to attitudes as those of Le Corbusier and Ernst May, the main objective of architecture for the authors is the thematization of its time spirit. Implicitly this attitude is arguing for the acceptance of whichever prevailing condition, which in a way means welcoming a context in order to be able to change it. What it also can suggest is that good architecture, as long as it reverberates the spirit of its time, automatically will be born out of any social, cultural and political context. Time itself becomes the primary subject 9 of architecture that in the best case will lead to progress (funnily enough, the name of the Swedish publisher of acceptera can be translated as The time). Acceptance as progress seems to eliminate the possibility of rethinking form as opposed to the asymmetrical power systems that more or less always shape architecture. It therefore neglects the overturning, critical project.

1 Asplund, Gunnar; Wolter Gahn; Sven Markelius; Gregor Paulsson; Eskil Sundahl; Uno Åhren, acceptera, Tiden, Stockholm, 1931, p. 303.

2 Le Corbusier, Towards an Architecture, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, 2007, p 267

3 Mattson, Helena; Wallenstein, Sven-Olof, Swedish Modernism at the Crossroads (English and German Edition) Axl Books, Stockholm, 2009, p. 40.

4 Asplund et al, 1931, p. 198.

5 Ibid. 1931, p. 15.

6 Eriksson, Eva, Den moderna staden tar form: Arkitektur och debatt 1910-1935 , Ordfront Förlag, Stockholm, 2001, p. 464.

7 Hedqvist, Hedvig, 1900 – 2002, Svensk form – internationell design, Bokförlaget DN, Stockholm, 2002, p. 58.

8 Eriksson, Eva, Den moderna staden tar form: Arkitektur och debatt 1910-1935 , Ordfront Förlag, Stockholm, 2001, p. 458.

9 Mattson, Helena et al, 2009, p. 44.