The City of Dead

Hélène Binet, text by João Coles

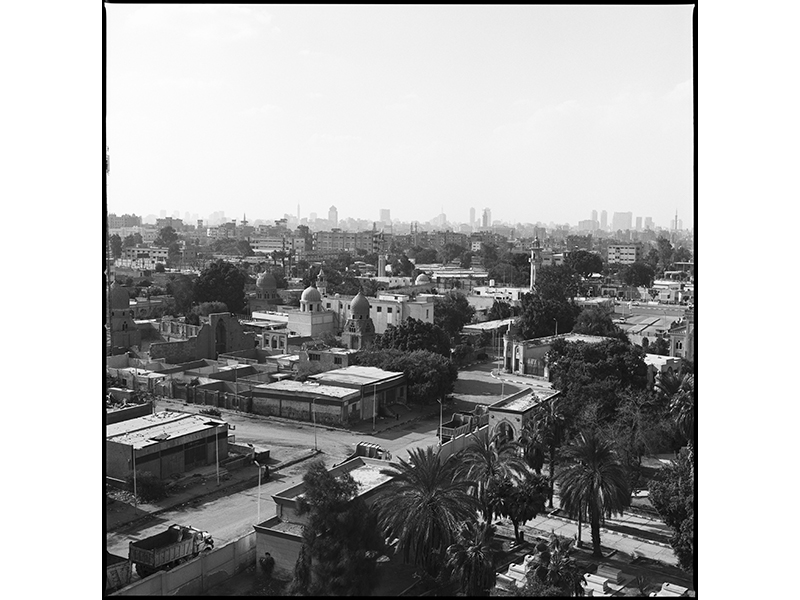

The City of the Dead in Cairo (El-Arafa) is one of the largest necropoleis in Egypt, founded in 642 by Amr ibn al-As the day after conquering the city. Traditionally, it was a burial ground for Arab conquerors and their families. The crypts in which they were buried, had a guard living in loco to […]

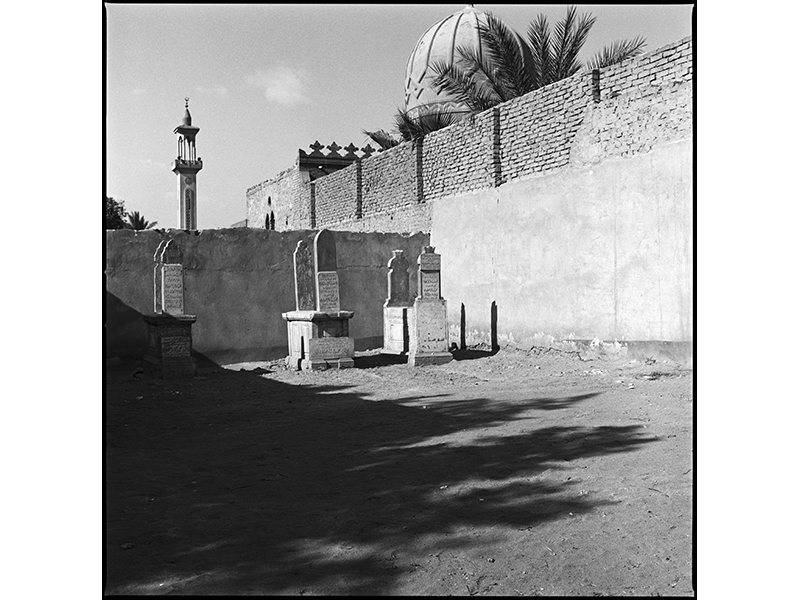

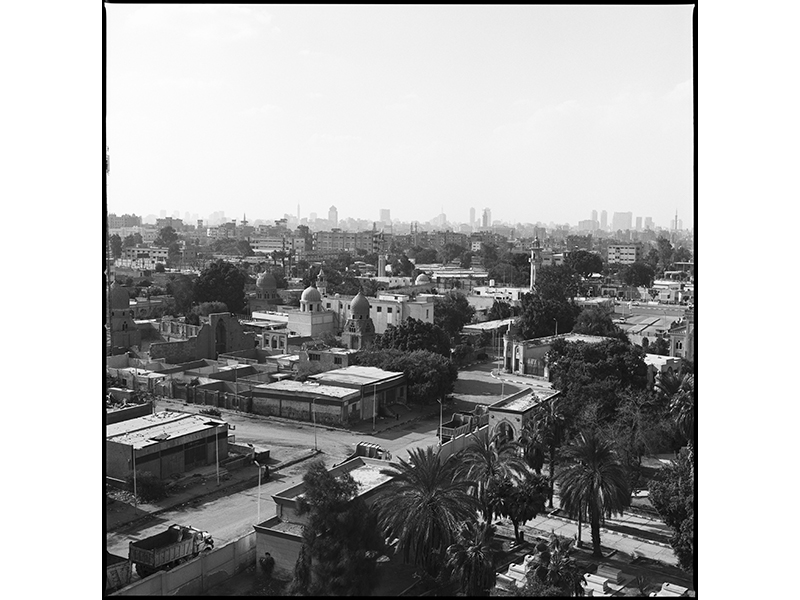

The City of the Dead in Cairo (El-Arafa) is one of the largest necropoleis in Egypt, founded in 642 by Amr ibn al-As the day after conquering the city. Traditionally, it was a burial ground for Arab conquerors and their families. The crypts in which they were buried, had a guard living in loco to protect the tombs, and were originally constructed as small houses in order to accommodate relatives who would come to visit and pay their tribute to the dead. Thirteen centuries later, the graveyard was occupied by a wave of desperate people who ended up inhabiting the space between tombstones. It is estimated that between 500 and 800 thousand people live in the necropolis.

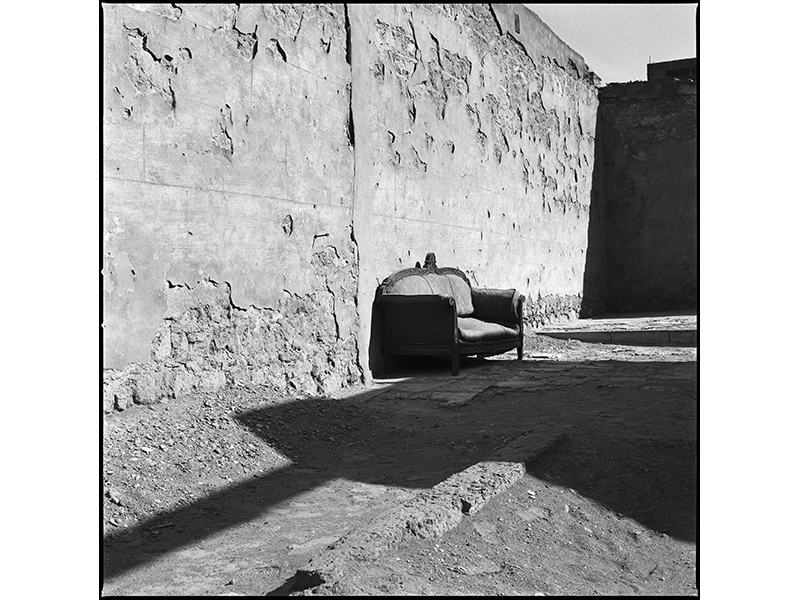

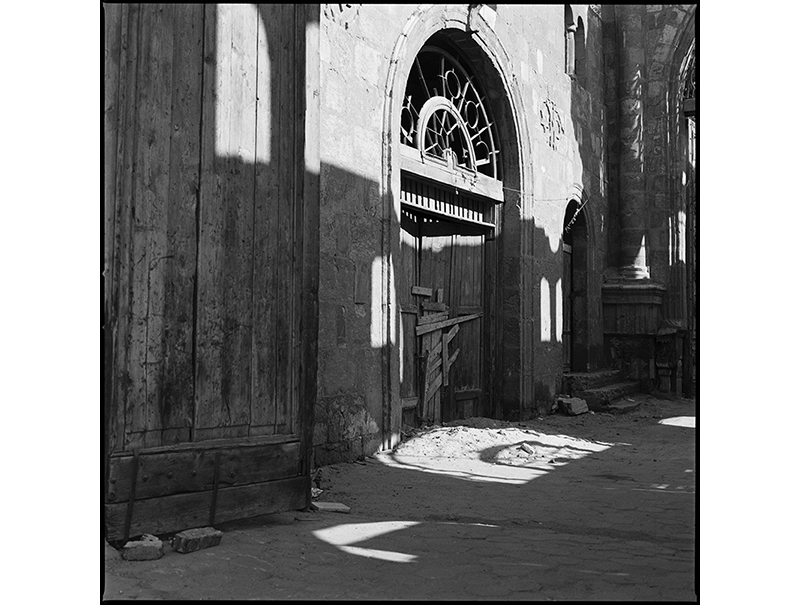

Appropriating the space that was once destined only for the dead, walking over the ground that covers the bones of past generations, and breathing the air mingled with the dust of their ancestors’ bones during their daily chores, are situations to which the inhabitants of El-Arafa are accustomed. It seems that living with the dead has brought them to be in good terms with their own mortality. Nevertheless, these people do struggle to survive, and it was surviving their condition in Cairo that brought them to occupy these spaces, appropriating them as permanent homes for the living. Some find work as guardians of the tombs for a trifle, some perform funerary services or clean the courtyards for money. These spaces in which they live underline their condition in a society that drove them to sunset, of human beings in a limbo between two worlds: the one of the living, to which they cling on to, and the one of the dead, that allows them to live and to cling on to the latter.

Visiting these homes is overwhelming, mainly during working hours, because it is possible to find some house-crypts empty. The sense of emptiness and occupation of space one can find in these photographs, the desolation and occupation that contrast in such places bring to mind more than ever the remembrance of death, of one’s own mortality – the frail condition of humans, how everything can go too quickly, how the transition from the living to the dead can be depicted from the relationship between an amphora and small pots or a sofa with the space they are occupying, as if telling us that the boundaries between the living and the dead are non-existent, of how survival can depend on the dead, of how the word survival, bared so lightly in language sometimes, is everything.

P.S. – These photographs were taken during a walk when Hélène was visiting her daughter Saskia in Cairo – January 2018.