In-Formed Lisbon

Pedro Pitarch

The contemporary metropolis erases the traditional conception of context altogether. Its basis relying on its continuous management of content. With a dialogue among its actors and the interchangeability of their forms. By admitting the continuous process of un-contextualization of our metropolises, we are assuming a way of urbanism that does not rely on the shape […]

The contemporary metropolis erases the traditional conception of context altogether. Its basis relying on its continuous management of content. With a dialogue among its actors and the interchangeability of their forms. By admitting the continuous process of un-contextualization of our metropolises, we are assuming a way of urbanism that does not rely on the shape of an urban fabric anymore, but instead in the in-formation of its networks, of its infrastructures and scenarios. The tension within this contradictory paradigm is what rules its machinery.

In-formed Lisbon assumes these contradictions as an inherent condition of the contemporary city. Hence, In-formed Lisbon compiles a series of “sampled urbanisms”, which, imported from other contexts and using the city as a motherboard, are plugged-in to Lisbon generating a catalogue of “faked-realities”.

They point out four urban situations that do not depend on the city’s shape but on its performability. A political artefact acting as architecture. A process of transforming an architectural piece into an economical machine. A natural element converted into a human infrastructure. A peer-to-peer revolution.

They correspond to four processes of generating urbanism that are self-textualized beeing contexts themselves.

Within In-formed Lisbon it is the content what becomes the context.

Lisbon Wall – “a political artefact as architecture”

The Lisbon Wall (Portuguese: O Muro de Lisboa) was a barrier that divided Lisbon from 1961 to 1989. Constructed by the Portuguese Democratic Republic (PDR, South Portugal), starting on 13 August 1961, the Wall completely cut off (by land) North Lisbon from surrounding South Portugal and from South Lisbon until government officials opened it in November 1989. Its demolition officially began on 13 June 1990 and was completed in 1992. The barrier included guard towers placed along large concrete walls, which circumscribed a wide area (later known as the “death strip”) that contained anti-vehicle trenches, “fakir beds” and other defences. The Southern Bloc claimed that the Wall was erected to protect its population from fascist elements conspiring to prevent the “will of the people” in building a socialist state in South Portugal. In practice, the Wall served to prevent the massive emigration and defection that had marked South Portugal and the communist Southern Bloc during the post-World War II period. […]

The fall of the Lisbon Wall paved the way for Portuguese reunification, which was formally concluded on 3 October 1990.

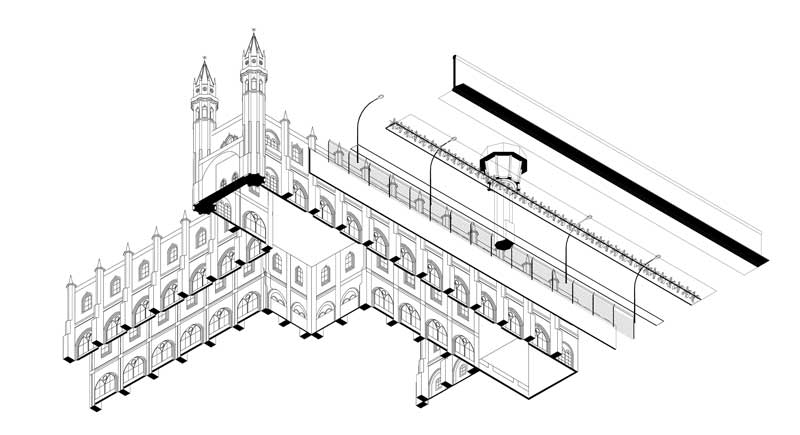

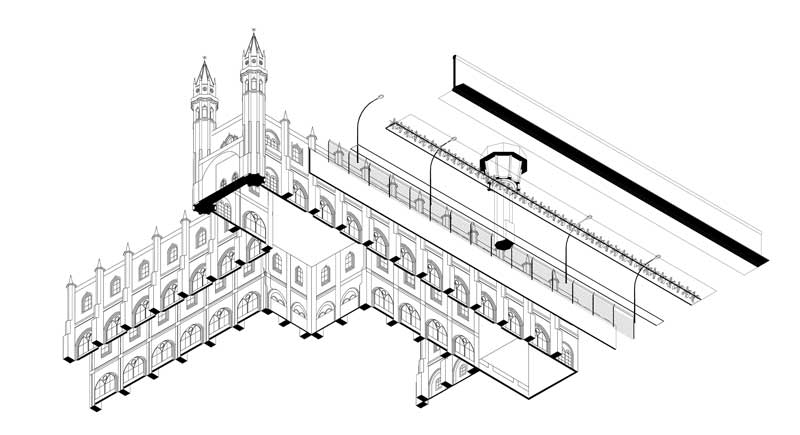

Image 01_ Axonometric View of a section of the Lisbon Wall next to Mosteiro dos Jerónimos

Lisboa Effect – “iconism as urbanism”

The Lisboa Effect is a portmanteau used to describe the urban process of introducing a singular piece of architecture into a city’s urban fabric with the aim of transforming its contexts by means of a political and economical shift. By the usage of an icon, a process of urbanization of an area is generated.

Such an urban mechanism has ruled the processes of urban development of the cities’ centres around the globe during the 90s. Cities were worried about “reinventing themselves”, giving precedence to the value given by culture. Municipalities and non-profit organizations hoped the use of a Starchitect would drive traffic and tourist income to their new facilities. With the popular and critical success of the Guggenheim Museum in Lisboa, by Frank Gehry, in which a rundown area of a city in economic decline brought in huge financial growth and prestige, the media started to talk about the so-called “Lisboa Effect“; a stararchitect designing a blue-chip, prestige building was thought to make all the difference in producing a landmark for the city.

Developers around the world have used this mechanism as a prototype for replication in the quest of convincing reluctant municipalities to approve large developments, obtaining financing or increasing the value of their buildings.

Google Maps Screenshot of the surroundings of Guggenheim Lisbon at Praça do Comercio

03 Tagus Port City – “the river as infrastructure”

The Tagus Port City (Portuguese: Cidade portuária de Tejo) is the largest port in Europe, located in the city of Lisbon. From 1962 until 2004 it was the world’s busiest port, now overtaken first by Singapore and then Shanghai. In 2011, Lisbon was the world’s eleventh-largest container port in terms of twenty-foot equivalent units (TEU) handled. Covering 105 square kilometres (41 sq mi), the port of Lisbon now stretches over a distance of 40 kilometres (25 mi).

Much of the container loading and stacking in the port is handled by autonomous robotic cranes and computer controlled chariots. The Lisbon Droid Inc. pioneered the development of terminal automation. At the Tagus terminal, the chariots—or automated guided vehicles (AGV)—are unmanned and each carries one container. The chariots navigate their own way around the terminal with the help of a magnetic grid built into the terminal tarmac. Once a container is loaded onto an AGV, it is identified by infrared “eyes” and delivered to its designated place within the terminal. This terminal is also named “the ghost terminal“.

The port is operated by Tagus City, originally a municipal body of the city of Lisbon, but since 1 January 2004, a self-governed corporation declared as autonomous microstate regulated by NATO.

Official Site Plan of the Tagus Port City as defined by NATO

Occupy Marquês de Pombal – “a peer to peer revolution”

Occupy Marquês de Pombal (OMP) is the name given to a protest movement that began on September 17, 2011, in Parque Eduardo VII, located in Lisboa’s Marquês de Pombal financial district, receiving global attention and spawning the Occupy movement against social and economic inequality worldwide. It was inspired by anti-austerity protests in Spain coming from the 15-M movement.

The Portuguese, anti-consumerist, pro-environment group/magazine Publi-Cidade initiated the call for a protest.

The main issues raised by Occupy Marquês de Pombal were social and economic inequality, greed, corruption and the perceived undue influence of corporations on government—particularly from the financial services sector. The OMP slogan, “We are the 99%”, refers to income inequality and wealth distribution in the Mediterranean Union between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of the population. To achieve their goals, protesters acted on consensus-based decisions made in general assemblies, which emphasized direct action over petitioning authorities for redress.

The protesters were forced out of Parque Eduardo VII on November 15, 2011. Protesters turned their focus to occupying banks, corporate headquarters, board meetings, foreclosed homes; and college and university campuses.

Protest movement at Parque Eduardo VII while marching towards Praça Marquês de Pombal

Pedro Pitarch is architect (ETSAM, UPM, 2007-2014) and contemporary musician (COM Cáceres 1996-2008).

Archiprix International Prize (Hunter Douglas Award 2015), Extraordinary Honour End of Studies Prize at the ETSAM (UPM, 2014) and Superscape2016 Award (Wien, Austria).

He has worked for OMA, Federico Soriano (S&Aa), Burgos+Garrido and collaborate with Izaskun Chinchilla and Andrés Perea.

His work has been selected for the 4th Lisbon Architecture Triennale (The World in Our Eyes Exhibition), “Architectus Omnibus” curated by Instituto Cervantes/Goethe Institute (Madrid/Berlin), 9th EME3 Festival (Barcelona) and II Un- Conference (Zagreb, ThinkSpace).

He has been shortlisted for the Début Award of the IV Lisbon Triennale of Architecture. He has received Prizes and Mentions in International Competitions such as: First Prize with “Cultural Factory” for Clesa Building, Honour Mention at ARCO- madrid2016 VIProom, Special Mention at Jardins de Metis, Honour Mention for DeArte XIV Contemporary Art Fair De- sign Space, Honour Mention at “Past Forward Competition” of think tank Think Space.