Notes on Aldo Rossi’s Geography and History; the Human Creation

Adrià Carbonell and Roi Salgueiro Barrio

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA Geography and History; the Human Creation “The history of the city is always inseparable from its geography” Rossi, The Architecture of the City, p. 97. Rossi’s interest in geography was not limited to the analytical framework it provides to describe the city. It expresses […]

CHAPTER II: PRIMARY ELEMENTS AND THE CONCEPT OF AREA

Geography and History; the Human Creation

“The history of the city is always inseparable from its geography”

Rossi, The Architecture of the City, p. 97.

Rossi’s interest in geography was not limited to the analytical framework it provides to describe the city. It expresses a deeper concern about the interrelations between architecture, territory and planning, which is very strongly developed in his writings of the early 1960s. (1) These texts already show a reaction to the modernist “ideology of planning”, to use Tafuri’s terminology, and an interest in articulating an architectural response to it. This response was aimed at fostering the collective and political dimension of space, in the belief that territory and planning were still the conditions that made any architectural project truly operative.

Rossi’s first account of the autonomous dimension that urbanism and architecture can have is aimed at finding a specific role for these disciplines within the mostly economically driven processes of territorial planning. In the collective volume Problemi sullo sviluppo delle aree arretrate published in 1960, Rossi significally starts his contribution with a critique to the totalising meta-geographical approach represented by Le Corbusier for its lack of relation to particular realities. (2) He advocates, instead, for an “elastic planning”, which he defines as “a planning of wide spectrum (referred to an area that constitutes a culturally and geographically unitary nucleus) which understands the project, abandoned of all simplicity, as the articulation of a process open to the diverse requirements, more sensible towards the local historical values, analytic and decentralised” (3). Rossi argues that the autonomy of the architectural and urban discourse introduces, within the strict economic rationality of the plan, the possibility of articulating a political space. Following Carlo Cattaneo’s work, this political space is referred to as a precise territorial realm: “The city forms with its regions an elementary body, this adhesion between the county and the city, constitutes a political persona, permanent and inseparable”. (4)

In Problemi sullo Sviluppo delle Aree Arretrate, Rossi considers that this territorial, political space could be articulated through a new form of settlement: an architectural complex that, joining residence with industry, production with inhabitation, would show the occupation of the region by a new political collectivity. In his subsequent writings, Rossi abandons this functional idea to consider, instead, that commercial and industrial buildings, infrastructures, and the like, constitute the elements that actually organise the territorial scale, while housing becomes an almost negligible element. What remains through this change of uses is the understanding that only architectural fragments can articulate the territory.

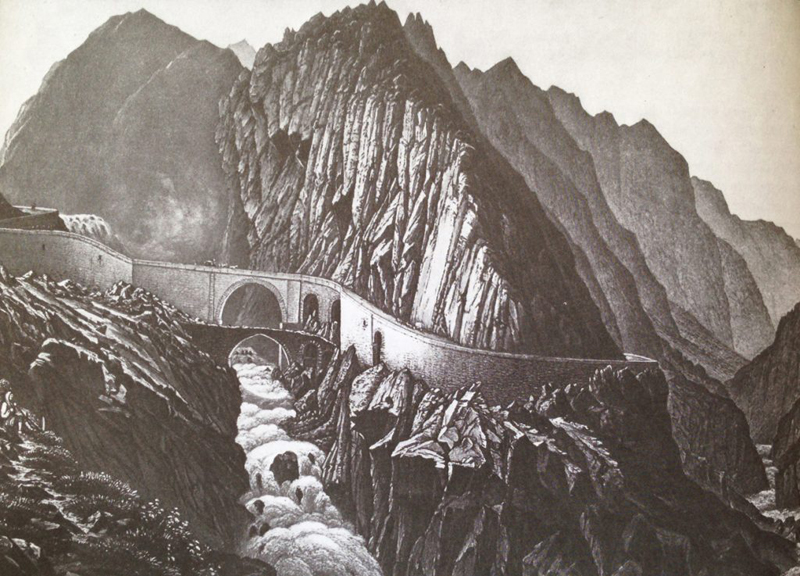

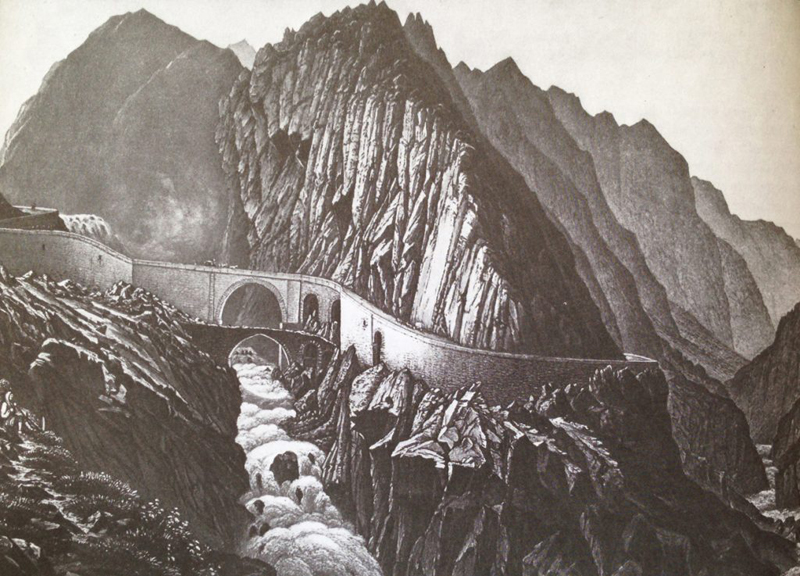

In this sense, the crucial differentiation between primary element and area — where the latter is predominantly residential — that Rossi establishes in The Architecture of the City can be seen as originating not in the city, but in the territory. Even if the notion of primary element, so central in the book, is the element that “characterises a city” and the carrier of its architectural value, it certainly transcends the scale of the architectural object. In Rossi’s words, a primary element “can be seen as an actual urban artefact, identifiable with an event or an architecture that is capable of ‘summarising’ the city”. (5) In a time where the definition of the urban has come into crisis, when extended urbanisation processes have taken a planetary dimension, more than looking at the city as a traditionally bounded, compact, and distinct formal structure, it may be pertinent to look back at the intertwined relations between architecture and geography, or in other words, at the construction of the territory as a “Human Creation”, with all its cultural, political and geographical dimensions. The city Rossi was trying to encapsulate in his theory was composed of a varied, complex and rich architectural imagery, reaching beyond the historic and modern repertoire of formal articulations. By broadening its classical definition, we may conclude that the form of the city is to be associated with its geography, its routes, highways and other infrastructures, the irrigation of fields and industrial settlements; thus, the form of the city would actually be the form of its territory. In this sense, Rossi participates of a generational concern, yet, unlike some of his contemporaries — like Saverio Muratori or Vittorio Gregotti who investigated how geography could contaminate architectural and urban form — the a priori formal autonomy of architecture that Rossi claims has the capacity to determine how the territory is going to be perceived and how it is going to be culturally and politically articulated. This may be one of the lessons we owe to Rossi’s The Architecture of the City, a book about the city that opens with the image of a bridge in the territory.

1 With regards to Rossi’s account of the relation between architecture, territory and planning, it’s interesting to note the evolution of his thesis in the position he held in the contribution wrote together with Silvano Tintori in 1960 for the collective volume Problemi sullo sviluppo delle aree arretrate (Problems about the Development of Depressed Areas), to the paper “New Problems” of 1962, to The Architecture of the City of 1966.

2 The volume was oriented to continue the intellectual work initiated in the 1954 International Symposium of Underdeveloped Areas, held in Milan, in which Le Corbusier participated. For Le Corbusier, a meta-geographical analysis was the basis of a theoretical model; one that could reconfigure France after World-War, but also the totality of Europe, to use his expression: “From the Mountains to the Urals”

3 Aldo Rossi and Silvano Tintori, “Aspettiurbanistici del problemadelle zone arretrate in Italia e in Europa” in Problemi sullo sviluppo delle aree arretrate, ed.Ajmone Marsan, V., Giovanni Demaria, and Centro Nazionale Di Prevenzionee di Difesa Sociale (Bologna: 1960), 248-9. Our translation.

4 Aldo Rossi and Silvano Tintori, Op. Cit., 251-252. Our translation.

5 Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City ( Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1984) p. 99.

Adrià Carbonell is an architect and educator based in Stockholm. He is Visiting Professor at KU Leuven, and has hold teaching positions at Umeå School of Architecture and at the American University of Sharjah.

Roi Salgueiro Barrio (MArch, MDesS, PhD) is a research associate at the MIT Center for Advanced Urbanism, and a member of the editorial team of Actar’s UrbanNext platform.