The City of Architecture

Daniele Pisani

CHAPTER III: THE INDIVIDUALITY OF URBAN ARTIFACTS, ARCHITECTURE Monuments; Summary of the Critique of the Concept of Context Reading Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City, one feels a constant sense of being one step away from suggestive, however elusive, conclusions. Made of insertions and movements, rethinking and omissions still partly perceptible, the text […]

CHAPTER III: THE INDIVIDUALITY OF URBAN ARTIFACTS, ARCHITECTURE

Monuments; Summary of the Critique of the Concept of Context

Reading Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City, one feels a constant sense of being one step away from suggestive, however elusive, conclusions. Made of insertions and movements, rethinking and omissions still partly perceptible, the text clearly demonstrates Rossi’s effort to enunciate an intuitive and poetic thought in rigorous and deductive terms, aiming at the construction of an “urban science”. This is also why The Architecture of the City is a palimpsest: to each explicit word corresponds a hidden one. The subchapter “Monuments: Summary of the Critique of the Concept of Context” is no exception. In order to follow the discourse, it is necessary to trace some virtual parenthesis or notes, unravel formulations so dense that they sound unfathomable, presuppose passages lost on the way, perceive the imminent presence of undeclared sources, shuffle incoherent sequences into the right order.

In the last lines of the previous subchapter, “The Roman Forum”, Rossi repeated his intention to understand the city as “pre-eminently a collective fact”. He intends now to carry out his “Critique of the Concept of Context” exactly in order to answer a question, although unformulated, which could be derived from the previous declaration: if the city “is of an essentially collective nature”, which role does architecture play in its “singularity”?

If we admit that this is the question Rossi seeks to answer, everything becomes clearer. Rossi’s polemical target consists here in the contrast between context and the monument (when he states “To context is opposed the idea of monument”, he actually does it to distance himself from this attitude). This is a contrast which, following the conviction of the “collective” nature of the city, should logically drive him to reframe the function of architecture. The whole paragraph reads therefore as a defence of the role of something “singular”, such as architecture, in the construction of something “collective”, such as the city; indeed The Architecture of the City.

Anyone expecting a following argumentation on this point will be let down. Yet, after many circumvolutions, Rossi’s answer does arrive. The topic of the book, as Rossi declares, is “architecture as a component of the urban artefact”; and “it would be foolish”, he goes on, “to think that the problem of architecture can be […] revealed through a context or a purported extension of a context’s parameters”. It would be foolish as “context is specific precisely in that it is constructed through architecture”.

Here is where Rossi wanted to arrive. He had already declared his agreement with authors who consider the city “pre-eminently a collective fact”, but he now wants to emphasise the fact that his conclusions diverge from those derived by others from similar premises. Architecture – allow me to freely paraphrase Rossi – cannot be deducted from context (which in Rossi’s terms has a negative connotation: it is the “permanence” as “pathological”). The city, he writes, is not built by means of the establishment of a general rule (deducted from context) that shall be applied to the particular case (architecture), but on the contrary, assuming that the latter shall be the fundamental “component”. Rossi had already expressed his opinion on this: “The assumption that urban artefacts are the founding principle of the cities denies and refuses the notion of urban design”. To the contemporaneous tendency to conceive the city following “volumetric-quantitative” standards, he coherently counters with the necessity to start from the building, “in the most concrete way possible”.

Following the logic of this paragraph, some affirmations spread across other pages assume a singular relevance, in particular: “Architecture becomes by extension the city”. In these words resonate an allusion – that seems to never have been noted – to a famous sentence present in Leon Battista Alberti’s and Andrea Palladio’s treatise, picked up by Durand in a fragment quoted in the book, but most likely mediated by one of Rossi’s contemporaries.

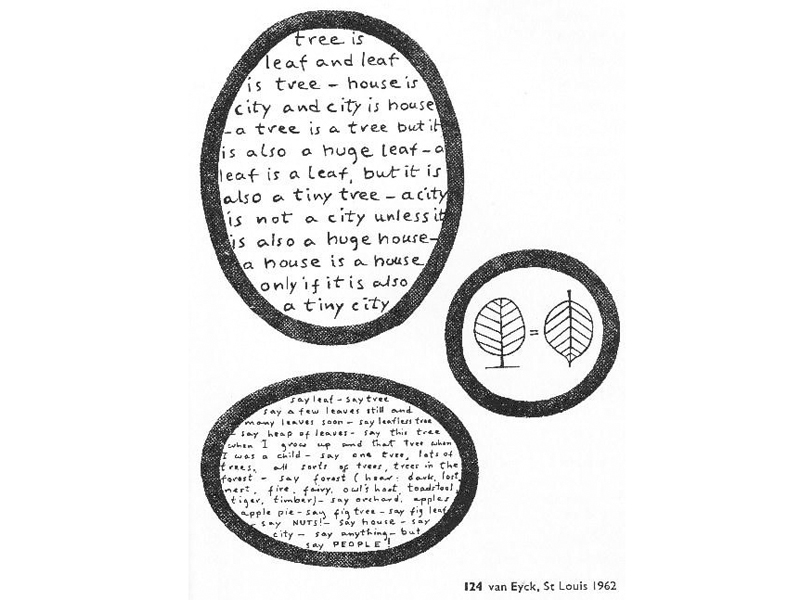

Aldo van Eyck had been repeating for years that “house is city and city is house”; he had stated it in Otterlo, he had just been repeating it in Domus. What was a chiasm for van Eyck becomes however a unilateral assertion for Rossi: house is city. The city shall be the objective of architecture (“The whole is more important than the single parts”), but it’s the architecture that makes the city, not the contrary.

Rossi is not trying to affirm that the project’s rational capacity to forecast is not unlimited. In his view, the world is complex; architecture is part of a play in which many actors are involved and, once built, it doesn’t belong to itself anymore. The fact is that architecture implies an instance of order that inevitably collides with others and with the “locus”. It is indeed from this conflict that la chose humaine par excellence originates: the city. For is it not Rossi himself who maintains that his book “is not concerned with architecture in itself but with architecture as a component of the urban artefact”? The City of Architecture.