The Form of the Collective Artifacts

Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS The Individuality of Urban Artifacts Three maps of three paradigmatic proto-cities are presented. The black and white plan drawings are stripped of information in order to highlight the bare form of the cities. As apparently abstract as they are, these documents immediately reveal forms that at this […]

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS

The Individuality of Urban Artifacts

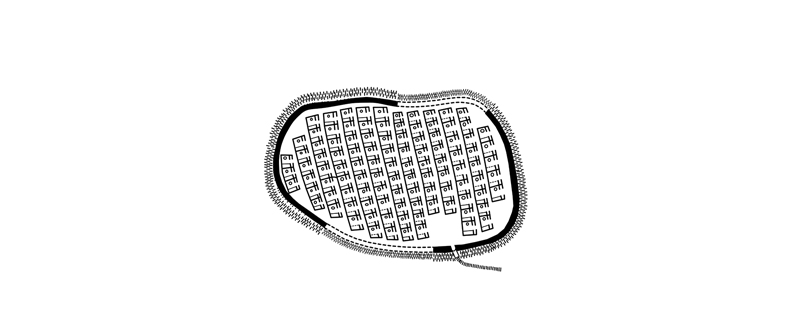

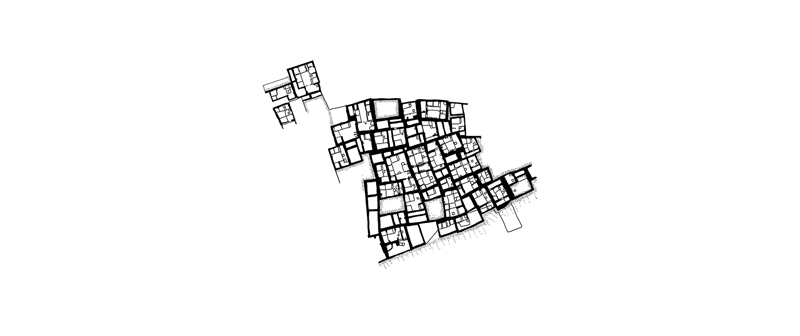

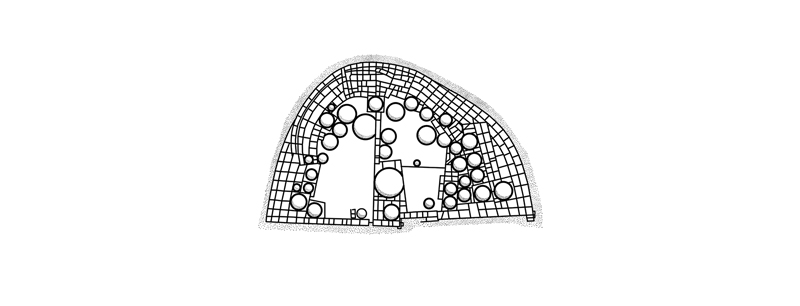

Three maps of three paradigmatic proto-cities are presented. The black and white plan drawings are stripped of information in order to highlight the bare form of the cities. As apparently abstract as they are, these documents immediately reveal forms that at this stage in history are capable of absorbing and communicating a large set of values connected to the construction of the city and its social organization.

The town of Çatalhöyük, today located in Turkey, the pueblos of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, and Biskupin in Poland, are three settlements belonging to three different times in history. While differing in their general urban planimetry, the three ancient cities bear several common traits that make them comparable.

First of all, the form of each of these primordial cities is instantly recognisable; second, the urban form is obtained from the continuous agglomeration of a basic, individual artefact: the single cell. This space hosts the bare functions of living, those we could call “domestic”, but it also embodies social meaning and ritual purpose; in Çatalhöyük, bodies were buried under the floors and the walls were painted with vivid, sacred images.

Only in the case of Chaco Canyon are the cells, called the “pit houses”, coupled with larger rooms, called “kivas”, which apparently hosted collective spaces. Even when these variations are introduced, the assembling rules that govern the whole urban system are repetitive and those that generate architecture are strictly interdependent with the ones generating the city.

In these proto-cities, architecture does not seem to “express only one aspect of a complex reality”, but is still able, at this age in history, to directly embody specific material needs and a clear social structure.

The social organisation lying behind the form of the three settlements appears, in fact, to be one based upon a community of equals, where everyone, regardless of gender or age, occupies the same social and physical space. The absence of a class structure implies an absence of formal representation of class differences: the construction of the material and spatial structures constituting the single architectures (walls, roofs, rooms), and the urban artefact as a whole, is in direct response to pure necessity.

The form of the city appears then as the result of a purely quantitative addition of domestic modules adapted only to topography and with the added value, especially in the case of Biskupin, of producing a defensive layer.

At this primordial stage, architecture has no individuality and, is one thing with the urban form. In the case of Çatalhöyük, the relationship is even more extreme as the roofs of the houses are used for communal activities, as well as serving as the only connecting infrastructure of the houses. One might say that the house absorbs all urban functions, material, and representative, and contains the rules to form (the form of) the city.

At the dawn of civilization and many ages before functionalism came to be an ideological setting for the construction of architecture and the city, even the most basic distinction of functions associated with specific spaces does not yet exist. The cell is the barest form of what will be the “house”, but is already something different from the primitive hut: it does not only protect from weather conditions and outside dangers, but settles the rules for sharing a territory, provides a collective meaning, and structures the form of the city.

Mariabruna Fabrizi (*1982) and Fosco Lucarelli (*1981) are architects from Italy. They are currently based in Paris where they have founded the architectural practice Microcities and conduct independent architectural research through their website SOCKS. They work as assistant teachers at the Éav&t, in Marnes La Vallé, Paris and at EPFL, Lausanne. They are the content curator of “The Form of Form” exhibition in the 2016 Lisbon Triennale.