Christine’s Shining Stones

Shou Jie Eng

In the opening of The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), we find Christine de Pizan seated in her study, distressed at the misogynistic treatment of women in the literature of her time.1 Her state of discomfiture is only interrupted by the arrival of three allegorical figures— the ladies Reason, Rectitude, and Justice—who have […]

In the opening of The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), we find Christine de Pizan seated in her study, distressed at the misogynistic treatment of women in the literature of her time.1 Her state of discomfiture is only interrupted by the arrival of three allegorical figures— the ladies Reason, Rectitude, and Justice—who have come to guide her in the construction of a literary edifice for the defence of women. In the text, the appearance of the figures is initially attenuated by Christine’s distraction. She is preoccupied by her feelings of precarity and a sense of exposure; for Christine, and to the reader, there is a sense of a woman’s space that is either only contingently held or falling into outright abeyance. A provisional quality therefore surrounds this first contact with the figures. Their arrival casts a ray of light on Christine’s lap, breaking through, but never erasing, the fact that the rest of her body remains in the shadow of provisionality.

Settlements serve as refuges against this sense of provisionality. The City of Ladies is one of the earliest proto-feminist literary constructions in the western European landscape, a reaction against the treatment of women in the early humanist tradition of the 13th and 14th centuries, seen particularly in Jean de Meun’s section of the Romance of the Rose and subsequently in Boccaccio’s Famous Women. The City is written by Christine as a collection of biographical narratives of notable women, organised using the extended metaphor of a walled city. In the space of the text, Christine depicts herself as narrator, protagonist, and builder of the city itself. Stories of women form the masonry of the city, bonded with mortar mixed in her ink bottle and trowelled by her pen. Material is combined with metaphor and emplaced into argument. Contra the prevailing denigration of women, the assertion is that the characteristics of the assembled personages—characteristics such as strength, knowledge, ingenuity, prudence, prophecy, and love—represent qualities that are to be esteemed and are common to women in general.

Christine with the Ladies Reason, Rectitude, and Justice. Christine de Pizan, La cité des dames (1413-1414), Français 1178, Département des Manuscrits, Bibliothèque nationale de France, 3 bis. Illuminated miniature.

Christine’s use of the walled city as her structuring metaphor points to the wall as the primary architectonic element of the City. The purposes of the wall have been extensively debated: whether it serves to protect those within, as in the cities of Troy and Thebes that are cited in the text, to enclose something of value, as in the figure of the hortus conclusus, or to exclude those without, as in the classical polis.2 Yet these views of the wall unduly privilege the material over the metaphorical. Its apparent solidity does not dull its numerous “shining stones,”3 and the defensive tenor it lends the city does not overwhelm the diversity of its embodied narratives.

Indeed, it may be productive to remain at the level of metaphor momentarily and regard the wall as a model, at multiple scales, of the tensions and simultaneities present in the discourse of the City. At the scale of individual stone-stories, Christine re-authors many of the biographies of the wall. A comparative reading of these stories reveals subjective aspects of narratives previously used by others, such as Boccaccio, in service of attacks on women.4 The story of Semiramis, foundational to both the City and Famous Women, is one example. Boccaccio’s telling regards the Assyrian queen as courageous and skilful in battle and politics, but deceitful in cross-dressing as her son, the king, after the death of his father, and ultimately as sinful in taking her son as her lover. Christine, on the other hand, does not mention any subterfuge, and explains the incestuous relation as justifiable, even practical, given the state of nature that she ascribes to Semiramis’ time. By contextualising and re-writing Semiramis’ biography, Christine places her in a virtuous position, presenting her as the “great and large stone…the first in the first row of stones in the foundation” of the city.5 In addition, the resplendence of the stones, which Christine frequently alludes to, is a result not only of this virtue, but also of the practices of authorship that she deploys. For the contemporary reader, Christine’s re-framing of the biographical stones allows us to see them from different points of view, rendering them as multi-faceted and shimmering, especially when regarded against the backdrop of previous tellings.

At the scale of the wall as an assembly, the individual stones are collected and brought together by the “grid of intelligibility” that a masonry wall provides. Hubert Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow provide a useful formulation of the grid as a set of practices that constitute, organise, and analyse disparate components.6 The grid blends stones of various historical, mythological, and personal narratives, drawing from diverse places and times. The placing of stones within the grid of the wall does not reduce their difference, their individual brilliance, but allows each unit to be visible while structuring the network of the entire edifice. The act of laying stones in the wall is also analogical to the emergent practice of the grid. While the initial disposition of the wall is laid out by Christine and Reason, ordinary women of all classes are enjoined by the conclusion of the text to participate in the continuous construction of the city through their everyday conduct. This is a grid that extends beyond the bounds of the city, and even the text: a fact highlighted by the accompanying illuminations that depict it as a city under construction, a nascent set of walls and half-framed roofs, contingent and full of promise.

At the scale of the city as a whole, the richness of the wall and its individual stones is likewise reflected in the range of spaces that are found in its urban form. Christine is careful to describe temples, palaces, mansions, inns, houses, and other public buildings, as well as generous streets and squares. Alexandra Verini connects the urbanistic diversity of spaces in the city with the diverse models of female friendship that Christine describes in the text. Spatial and inter-personal relations in the city are unrestricted by binary, public/private domains of the classical (and male-dominated) polis.7 If Christine begins the text from a place of precarity and provisionality, the city that she constructs by the end sets out a collection of safer spaces for women that also allow for a more generous and fuller unfolding of disparate voices.

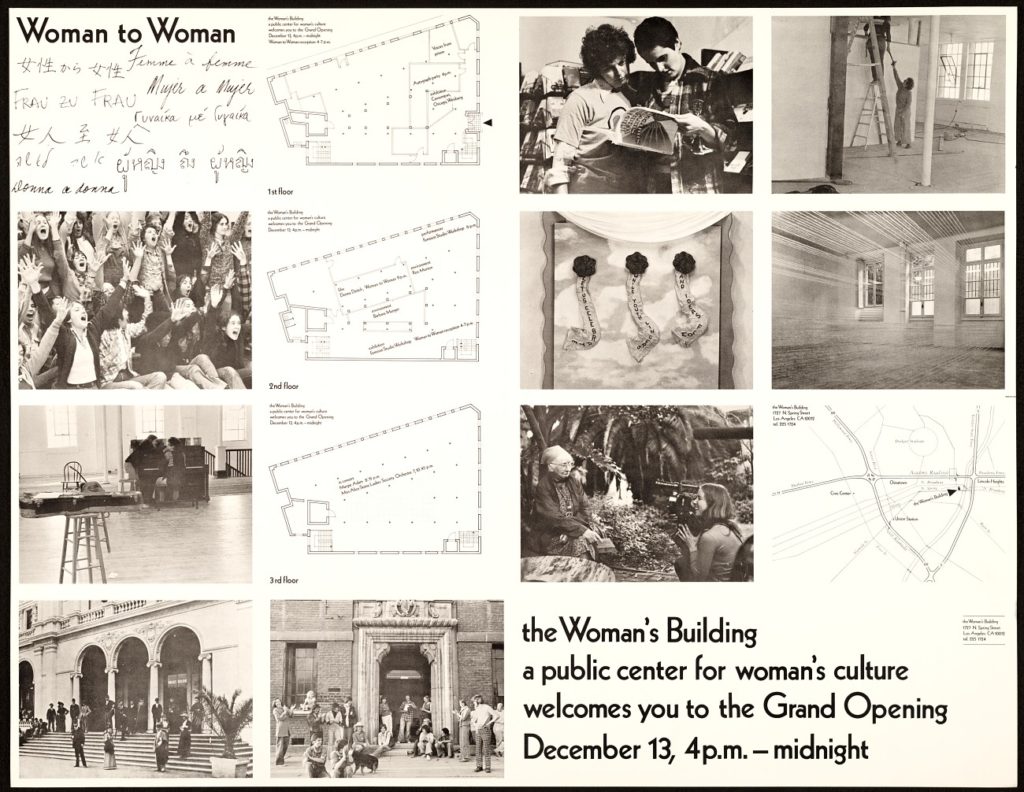

The Woman’s Building provides public spaces and galleries for individual shows, group efforts, collaborative events, and performances. Here woman’s work and art is honored and made known. We invite all of you to participate with us in the creation of a woman’s culture. 8

Numerous communities have been constructed since the City of Ladies, six hundred years ago, with the similarly ambitious goal of providing refuge to women (and other marginalised groups) while accommodating the differences between them. The Los Angeles Woman’s Building and its predecessor, the Feminist Studio Workshop, active in downtown Los Angeles from the 1970s to 1991, presents an intriguing example. Founded by an artist (Judy Chicago), a graphic designer (Sheila de Bretteville), and an art historian (Arlene Raven), the Building and Workshop grew out disillusionment with the philosophical, organisational, and physical confines of the institution of the art school—in their case, the California Institute of the Arts.

Exhibition poster for Woman to Woman at the Los Angeles Woman’s Building. Sheila Levrant De Bretteville, Woman to woman exhibition poster (1975), Woman’s Building records 1970-1992, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, recto.

As with the City, the early days of the Woman’s Building arose from a situation of precarity, and the founders met it by endeavouring to create an alternative space for feminist art education. They recognised that the act of building was also an act of building a community and incorporated the labour of constructing space into the education of its initial members and students. Women framed and plastered walls, moved studio equipment and furniture, and sanded and finished wood floors. A student recalled realising over time that she developed her ability to “make stuff” through this process.9 Recalling the open-ended grid of the City, individual members constructed a “web of human relationships,” in Hannah Arendt’s terms: a network of individual actions that makes visible the actor, as well as a body of viewers, each recognising themselves and each other as participants in a communal project.10 One sees this in photographs from the Building. There are few images of an individual that do not also consist of a body of women behind her, seeing her, and seeing themselves through her.

Critique of the Woman’s Building can be made along the lines of critiques of the City of Ladies, focussing on the insularity and defensiveness of the wall. Scholars have noted the exclusionary and conservative nature of organising a society fixed on virtue, and similarly, the later years of the Building saw recurring questions about the organisation’s ability to accommodate differences within its membership, particularly in relation to race and sexual orientation. But in the face of these challenges, the metaphoric possibilities of the wall as discursive model must be restated. Its ability to locate multi-faceted and diverse stories within a shifting, shimmering grid remains full of potential. Perhaps appropriately, for the opening of the Woman’s Building on North Spring Street in 1975, a poster was designed. Laid out on a grid, the verso of the sheet contained crop marks, revealing that the poster could be cut into postcards for distribution, each with details of the Building and short, potent, statements of purpose. The printed matter recalls the City: simultaneous, episodic, provisional, brilliant, and open-ended—

1 Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, trans. Earl Jeffrey Richards (1405; New York: Persea, 1982).

2 See Sandra L. Hindman, ‘With Ink and Mortar: Christine de Pizan’s Cité des Dames,’ Feminist Studies 10, no. 3 (1984), 470-471.

3 Christine, City of Ladies, 99.

4 See, for example, Jane Chance, Medieval Mythography, Volume 3 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2014), 5-8.

5 Christine, City of Ladies, 38.

6 Hubert L. Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow, Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, 2nd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 120-121.

7 Alexandra Verini, ‘Medieval Models of Friendship in Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the CIty of Ladies and Margery Kempe’s The Book of Margery Kempe,’ Feminist Studies 42, no. 2 (2016), 374- 376.

8 Sheila L. de Bretteville, Woman to Woman exhibition poster, 1975, 45 x 58 cm. Woman’s Building records, 1970-1992, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

9 Jane F. Gerhard, The Dinner Party: Judy Chicago and the Power of Popular Feminism, 1970-2007 (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2013), 73.

10 Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (1958; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 182-184.

Shou Jie Eng is a designer, researcher, and writer, whose work examines the relationships between spaces, bodies, and the material histories and cultures of craft. He runs Left Field Projects, a studio practice located in Hartford, Connecticut. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Tupelo Quarterly, Speculative Nonfiction, Ritual and Capital, and The Ekphrastic Review. His visual work has been presented at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, and the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park in San Francisco, California. He received his graduate degree in architecture from the Rhode Island School of Design, and previously taught at Roger Williams University.