Editorial

CARTHA

This year’s cycle of Cartha is exploring the pre-organized structures that the contemporary individual is facing—the foundational, yet imperceptible, forces that shape society and emerging environments. Major shifts in the recent global narrative are less an exception to the norm than they are the heightened exposure of prescribed systems of social organization. These sprawling micro/macro symbiotic systems have always existed, the cyclical […]

This year’s cycle of Cartha is exploring the pre-organized structures that the contemporary individual is facing—the foundational, yet imperceptible, forces that shape society and emerging environments.

Major shifts in the recent global narrative are less an exception to the norm than they are the heightened exposure of prescribed systems of social organization. These sprawling micro/macro symbiotic systems have always existed, the cyclical nature of attempting to order the world and the social conditioning in return: between bodies and technology, wherein we simultaneously produce the apparatus and are produced by it; the virtual representations of the self and their deep reverberations within the psyche; or the environments we create and their resulting authority over our habits and routines. The ways in which things produce each other can be inevitable, but where do the biases lie considering the multitude of stakeholders participating to create new forms of organization? What sort of narratives emerge as consequence? The interest lies in the infrastructures of taxonomies: not only who writes the script, but how you read it, and in what space it needs to perform.

BELIEF IN MYTH AS HISTORY

At one point, cosmology, as the study of and attempt to understand the universe as a whole through systems of inherited belief, structured our understanding of societies, cities and nations. It is described by Walter Benjamin in his Theses on the Philosophy of History as messianic time, or a simultaneity.1 Cosmology and history could, prior to the reformation and print capitalism2, be viewed as one; the origins of the world and the origins of man as identical. Time, events, history and the present society linked by the idea of an ultimate condition, a highest metaphysical state of history which appear as imminent states of perfection, able to manifest themselves anywhere and at any time. This pre-reformation cosmology required an unquestioning belief in the power of a certain script-language to offer access to higher truths, and a trust in the natural organisation of societies into hierarchical structures. A slow change in the perceived validity of underlying cosmological facts through systemic economic changes, the invention of societal and scientific disciplines, and the increase in global communications led to a split, finally a chasm, between history and our understanding of the universe as a whole. New ways to understand and structure the world through categorisation and classification became a necessity and a power.

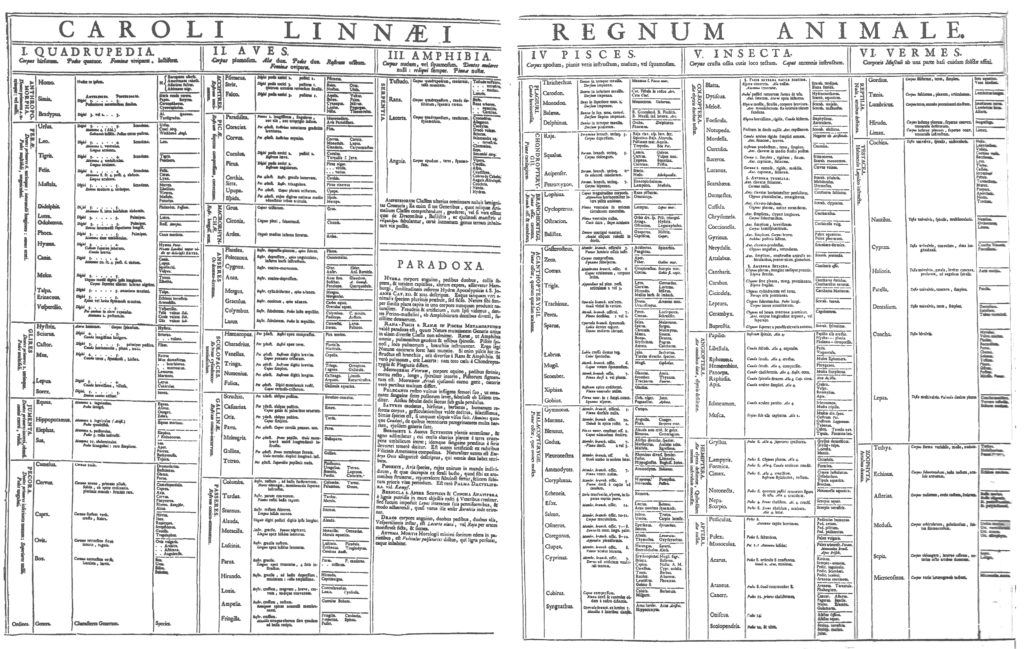

The quintessential book of taxonomy, Systema Naturea was published in 1735 by Carl Linnaeus, organizing the‘entirety’ of the natural world into a hierarchical classification system with binomial nomenclature under what he titled the “Linnean taxonomy”.

Linnaeus, Regnum Animale in Systema Naturae, 1735.

CLASSIFICATION AS A POLITICAL ACT

These fixed systems were questioned in the XXth century for being too reductive to be able to organize an ever-changing world. Michel Foucault published The Order of Things, building an entire discourse off of an invented system of taxonomy by Jorges Luis Borges, wherein the seemingly comical groupings of animals with loose visual resemblances exposed humanity’s irrefutable trust in the facts of science.3 However, these dichotomous categorization strategies continue to govern the way reality is understood through endless classifications in binary thinking or opposition logic, consistently relying heavily on the human eye’s authority over the other senses to structure the world.

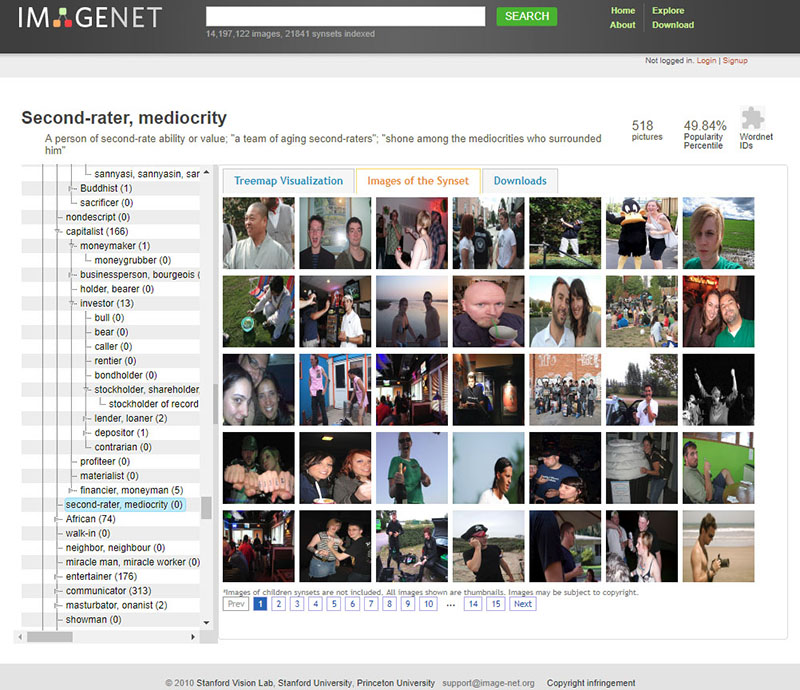

In recent times, the same stereotypical, culturally arbitrary and ethically exempt strategies are once again being employed to organize society in the development of taxonomies involved in training AI systems. Trevor Paglen’s studio emphasized this major hole in computer processing in his project ImageNet Roulette in 2019: he employed the same data set used to train basic image search algorithms to categorize people. The background processes are similar to that of the Linnean taxonomy, equally as unaccommodating of subtle difference and adaptive change, simply grouping people with similar visual traits and expressions as being cut from the same cloth. The over-categorization of everything continues, once again directing the evolving understanding of society and culture increasingly towards eugenics and biopolitics, but now differing in opacity: what once was clearly a celebration of man over nature is now cloaked in a ‘black box’, where the daily impacts of these deeply biased invisible structures go generally unnoticed.

Imagenet taxonomy tree showing images classified

as ‘second-rater, mediocrity’. ©Stanford Vision Lab 2010.

Cartha asked specialists in computation, history, the arts, sciences and economics to contemplate the ways that these types of systems participate in their research. Associate Professor in Architecture Curtis Roth, Reader in History of Art and Design Dr. Annebella Pollen, Emeritus Professor in Economics Herman Daly, Max Planck fellow Dr. Meritxell Huch with artist Alex Thake make up the Prologue of Invisible Structures, sprawling out from the discipline of architecture, provoking a series of questions for reflection in our next Open Call for Submissions.