Power Pursuit of Political Urbanism: Recounting Housing Prototypes & their Domestic Narratives

Simran Singh

The porous nature of urbanism involves a multi-disciplinary spectrum of stakeholders, where state agenda – if mostly veiled – is of the highest priority. A political play at emotions helps governments steer the present narrative towards visionary proposals that would alter past failings for an ambitious future. Once hailed as pioneers, a plethora of failed […]

The porous nature of urbanism involves a multi-disciplinary spectrum of stakeholders, where state agenda – if mostly veiled – is of the highest priority. A political play at emotions helps governments steer the present narrative towards visionary proposals that would alter past failings for an ambitious future. Once hailed as pioneers, a plethora of failed housing projects such as Robin Hood Gardens and Heygate Estate in London or Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, were also targets of experimentation; be it post-war, poverty alleviation or socialist mass housing. However, underneath the humanitarian scheme of providing shelter as a basic necessity runs a grim dimension of progress: that of biopolitics.

1.The Narkomfin

Davies, Katie. “Narkomfin: Join Architect Alexei Ginzburg for a Night Celebrating the Best of Russian Constructivism.” The Calvert Journal, 8 Mar. 2018

If the workings of the familial mechanism relate with the existing social organization, and if the family were the foundation of improvement in the standard of living, then what design methodologies were architects employing to strategize housing as a consequence of the-then political debates?1 Were the liberal, conservative, communist or utopian socialist attempts to strengthen the state’s power by regulating the family a successful step towards progress?

If we were to believe that the ends towards which urbanism strives are always greater than the immediate project, then typologically tracing the influence of architecture on the individual’s domesticity becomes pertinent. Rather than retracting to blind faith on new technology’s efficient and modular residences that arms the government with control, it is necessary to search for essential housing morphologies as a call of the hour.

1.

“… to replace our present haphazard arrangements, WE MUST BUILD IN THE OPEN. The layout must be of a purely geometrical kind. Unless we do this, there is no salvation”, proclaimed Le Corbusier.2 Marx too, brazenly declared an impending Communistic revolution to ease housing shortage. The abolishment of private property was the solution against capitalism: “On what foundation is the present family, the bourgeois family, based? On capital, on private gain.”3

Their love child was the Narkomfin (image 1) in the Soviet Union. Ambitious for a modern, technological and socialist society, Constructivist architects like Moisei Ginzburg relentlessly pioneered the interconnected anxieties of urbanism, mass housing and standardization.4 Corbusian overtones were apparent in Narkomfin’s elongated and slender slab. Poising on pilotis, its attitude is multi-scalar; the transparent ground maintains a rhythmic continuity of the city across the block, while the raised machine frees the worker from his daily strenuous activities to a conscious, if flitting, behaviour. Characterized by a singular boundary, the dialectical quality of the wall established between standardized dwellings and the centralized corridor is discredited by the horizontal ribbon windows on both sides. The worker’s perception is diminished and classified; the ambiguous façade is a control device which instructs a correct appreciation of a floating landscape.5

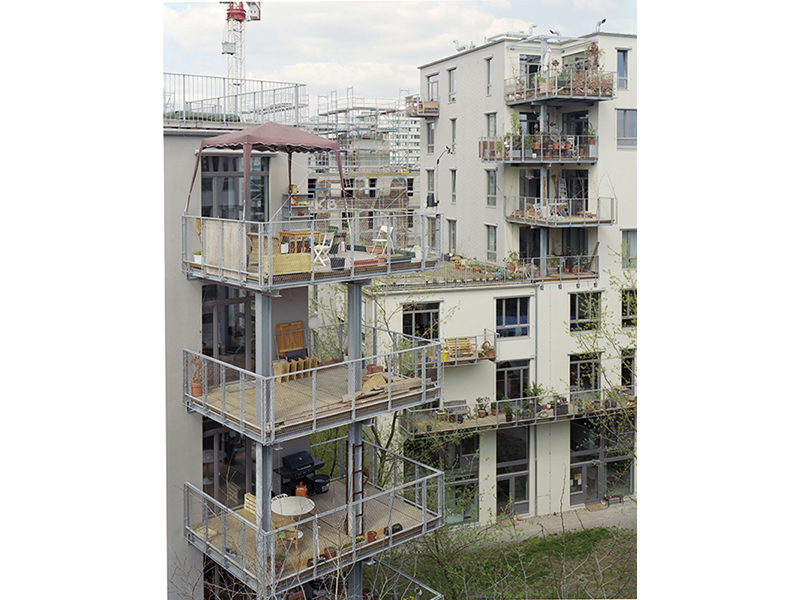

2.Domestic Theatrics at Spreefeld Architekten, Fatkoehl.

Here, the sojourned rigid plan, teasing a highly disciplined structuring of its social housekeeping under one communal block, was a futile attempt at a transitional housing. Its similar programmatic resources of a gym, kitchen and dining hall, however, shares a much-integrated spatial organization at the implicitly collectivized living of Spreefeld, a co-housing project in Berlin (image 2). Here, the differentiated architectural elements assembled within its three monoliths in a loose open configuration offer multiple opportunities for individual expression.6 Beside the domestic paraphernalia personalizing balconies, decks and terraces, a visual participation overlooking the various rituals of arrival and engagement is encouraged from the full-sized windows of the dwellings. While both projects were test models for a new architecture of fostering community beyond the nuclear family, the typological attitude of ‘glory in separation’ of Narkomfin versus the non-hierarchical flexibility of Spreefeld propelled the advantageous communal security into isolated living for one and a culture of trust for the other.7

2.

“For decades, Aylesbury residents have found ways to cope with, or even enjoy, their derided environment. When the scale and the problems of the estate get too much, says Fudge, ‘You close your front door, and you get a sense of a refuge. I have a three-bolt front door’.”8

A narrative common in many welfare housing – the establishment of which implied a point of departure from housing as a place to housing as an activity – asks for speculation whether the smaller and empty plots left untouched by the monopoly of large companies post-Berlin Wall triggered the success of the communal housing movement in Berlin. The new form of ownership and sharing culture ushered in was foundational to escaping the ‘my-home-is-my-castle’ dream of a late-capitalist individualism as well as the universally delusional “desire for the shelter, privacy, comfort and independence that a house can provide.”9, 10

Yet, the reality of society’s highly ideological constructs of preservation of the family exists within the notion of architecture to engender meaningful social change by exercising their power through the image, form and organization of the domestic sphere.11 Ironically, the sense of belongingness integral to an ambiguous collective of nuclear families was compromised in the ambitious mass housing developments, a consequence of the overburdening subjection of a single architectural concept. To avoid the isolated towers set within rambling green carpet as well as the forced neighbourly ‘streets in the sky’ access of slab housing, the short-lived housing production agency of Urban Development Corporation (NY) invariably produced the recurring troubles of “housing for poor people” through the low-rise, high-density blocks of Marcus Garvey Park Village, Brooklyn (image 3).

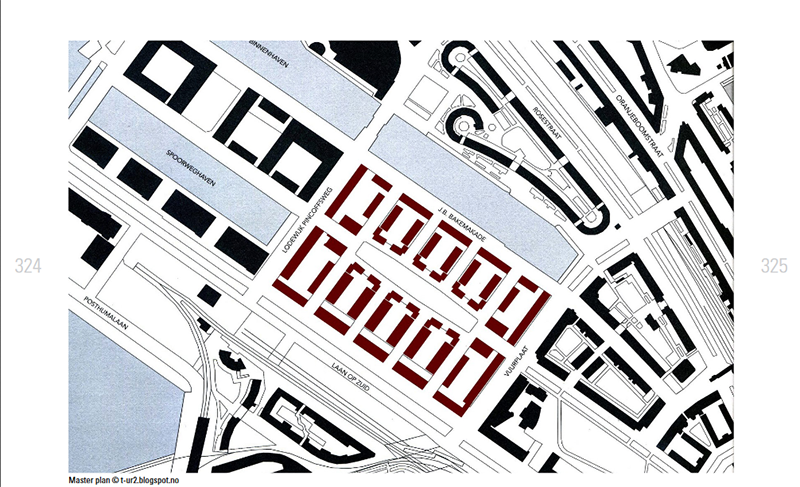

3.. Variation in the Open/Built Hiearchy of Stadstuinen

“Stadstuinen, Koop Van Zuid, Rotterdam. 2000-2001. Https://t-ur2.Blogspot.com/ Search?q=Stadstuinen, 2010, t-ur2.blogspot. com/search?q=Stadstuinen.

Similar to Alexander Klein’s balanced plans of a functional house, the variation of its dwellings and close-knit yet ordered family arrangements ensured the smooth running of a frictionless living.12 When indirect, the positioning of the entryway into an apartment maintains a diagonal stronghold over the strict and necessary traditional environment. Here, mum and dad are in control of the divisions and engagements of the household where the dominant kitchen and its table shapes the everyday. It is foundational in celebrations, central in child policing through the parental obligations of homework and care, and acts as a watchtower over potential terrors between the thresholds of public and private.

As a singular linear block, the six to eight repeating cells of two flats around a vertical circulation core is the ideal. Within an estate of self-repeating layout, however, the need for safety misinterprets as matters of interference and the independent flat access along the redundant streets subsequently draws the outside empty of any domestic conviviality. Unlike the traditional city where ensuing square and street provided a legible structure to the ground by acting like a public relief valve to alleviate density, the voids here are staged, just like the stoops implying a sense of ownership simply as a theatre of existence.13

Marcus Garvey Village’s rhythm of built and open space is determined by the individual defining themselves first in contradistinction to the pre-existing collective. This is an act of closing contrary to the act of opening in Stadstuinen, Rotterdam, where the individual beings form a community together (image 4).14 While the two projects share the same density, typology and precedent of the Berlage perimeter block model, the latter’s scale, hierarchy and orientation of its structured open spaces critiques the present dominant agglomeration of urban objects and the plausibility of their exact possible multiplication. In our fixation for quick progress as a representation of our erratic ideals and ethos, how does one avoid the congeries of conspicuously disparate living machines and instead facilitate identification and diversity?15

Generic at first glance, Stadstuinen’s sectional variations amalgamate into a much more coherent whole, drawing upon the tactics of a reductive disestablishment of the bourgeois niceties of cosmetic hierarchies. The aggregation of three different dwellings types generate an event structure around the shared, elevated ground, the nonspecific flows of which liquefies the rigid programming of the family life inside. Here, the undifferentiated inside-out relationship weaves together the secure interior with an individualized exterior, along with the vestigial and primary spaces into a coherent matrix.16

Central to the aforementioned precedents is the conflict between the individual and the collective, the sceptics of modern architecture debating the abstraction around competing political and philosophical theories as failures of tangible experiences.17 Maybe the critical discovery of real and instrumental collaboration between architecture and freedom aligns with the plight of dwelling that Heidegger writes about in Building, Dwelling, Thinking: “The proper dwelling plight lies in this, that mortals ever search anew for the essence of dwelling, that they must ever learn to dwell. What if man’s homelessness consisted in this, that man still does not even think of the proper plight of dwelling as the plight?”18 Yet our existing conditions and the projected trajectories dictates a set of behavioural instructions as a form of enforcement that manifests in social, legal and moral codes. At their total collapse and traumatic despair, when the very foundation of a person’s identity is under threat, it’s no wonder that one sometimes takes it out on the physical world.19 What if a state of equal and synchronized collaboration is the ideal progress?