The Kurtna Kolkhoz: Architectural Representations of Soviet and Post-Soviet Policy

Sonia Sobrino Ralston

Estonia’s rural architectural heritage is exemplary of the dramatic effects of soviet and post- soviet policy in terms of aesthetic, land ownership and agricultural policies. Estonia only came to be independent from 1920, and in 1940 the soviet occupation of Estonia began and lasted until the fall of the USSR in 1991. The soviet occupation […]

Estonia’s rural architectural heritage is exemplary of the dramatic effects of soviet and post- soviet policy in terms of aesthetic, land ownership and agricultural policies. Estonia only came to be independent from 1920, and in 1940 the soviet occupation of Estonia began and lasted until the fall of the USSR in 1991. The soviet occupation and had many policies that deeply affected the social, economic, and geographic make-up of the country, though the collectivization of agriculture had a particularly widespread effect on the nation’s people. The collectivization of agriculture which began in the late 1940s constituted a radical change in terms of the forcible movement of rural people into collective farms, where agriculture was converted into a large-scale operation mitigated by the state rather than through small family farms as had previously been the case. The USSR ultimately motivated the processes of collectivization in the countryside through land ownership policies and agricultural policy, but perhaps most interestingly these policies were also enforced through spatial and aesthetic policies that decided the architecture of the new collective farms. Valve Pormeister’s 1965 Experimental Poultry Farm administration building in Kurtna, Estonia lies at the intersection of these policies; not only is it an example of soviet-era agricultural, land ownership, and aesthetic policy, it also serves as an example of the complicated relationship toward soviet architectural heritage in the post-socialist period. The Kurtna collective farm therefore is not only illustrative of an Estonian architectural heritage, but also serves as an opportunity to better understand the continued implications of soviet rural policies in the Cold War era.

The Soviet Union’s rural policies—particularly the collectivization of agriculture—resulted in the construction of many collective farms of which Kurtna is just one example. The principle of collectivization in theory was to abolish private farms and replace them with kolkhozes, collectively- owned farms, and sovhkozes, state-owned farms.1 Under Joseph Stalin, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party from 1928 until his death in 1953, the aim of collectivization was to reduce the amount of labour dedicated to agricultural work by mechanizing and industrializing farming processes, and therefore freeing up labour for industrial work in cities.2 The implications of collectivization on the livelihood not only of Estonians but all of the USSR was dramatic; the coercive placing of farmers into collectives involved the murder and deportation of hundreds of thousands of people. 3 The “liquidation” of kulaks—land-owning farmers who hired paid help—was an important aspect of forced collectivization as it converted all privately-held land into state-owned land.4 It is estimated that roughly 120,000 Estonians were deported while another 70,000 fled the country in 1940, resulting in a large foreign Estonian population.5 As a result of these measures, by the 1950s the collective farms consolidated into just under 200 larger farms made up of several hundred families—though the productive capacity of these farms was highly limited due to an inability to provide the mechanization technologies originally promised.6 The coercive and destructive rural policies under Stalin freed up the countryside for a dramatic reinvention of landownership and as a result, the organization of farming infrastructure and rural land.

The Kurtna collective farm, hereon referred to as the Kurtna kolkhoz, was a result of the Stalinist legacy of collectivisation and land ownership policies, though its architectural ambition was enabled through Nikita Khrushchev—Stalin’s successor from 1953 until 1964—and his rural development policies. Khrushchev’s central intention in both urban and rural planning policy was primarily concerned with providing more adequate living conditions in both settings, and also to continue to modernize and industrialize the nation after intense devastation under Stalin and in postwar reconstruction. The main motivation for planning in urban areas was to deploy prefabricated apartment blocks in conjunction with planned neighbourhood units including administrative buildings, schools, and leisure spaces.7 With this development strategy for urban areas, Khrushchev had a concerted interest in following the Leninist ideal of bringing the urban to the rural, that is, to modernize rural areas through architecture and urban planning.8 The application of the urban model to the rural therefore resulted in policies promoting mass apartment-style housing in rural areas with centrally located administration and institutional buildings. This methodology of architecture and planning is most closely related to the typologies of company towns in the US, in that all of the services and housing for company workers was provided in the model.9 Beyond just an improvement for the living conditions of rural people, the use of urban policy in rural areas also was a continuation of collectivization policies in that it continued to seek a more modernized agriculture industry to move labour towards cities. Furthermore, the streamlining of Estonian agriculture in particular was important as Estonia provisioned not only its own population, but also a large part of the Leningrad area.10 In this respect, the collective farms relied on intense modernization policies mirroring architectural and planning policies in cities as a means to more efficiently farm and provide for the market.

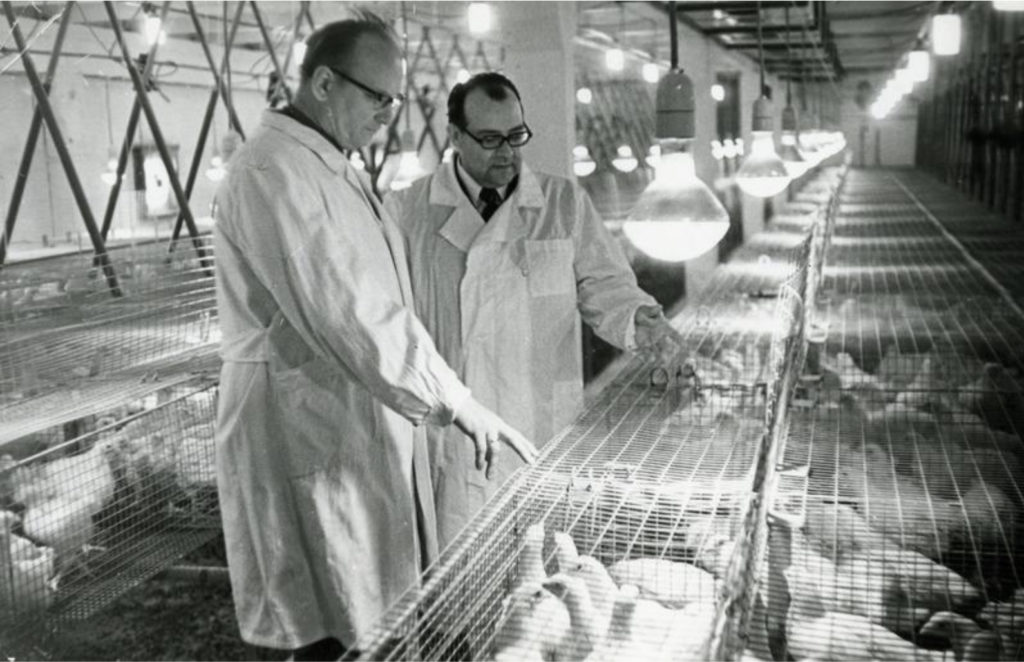

The scientific imagery in Pormeisters’ Kurtna Kolkhoz.50

In terms of agricultural production, the Kurtna kolkhoz was designed with the aim to develop experimental breeding practices for high pedigree poultry.11 Poultry breeding was historically of interest in Estonia, with the Estonian Poultry Breeder’s society formed in 1919 and a continued professional organization existed throughout the soviet occupation.12 Though Soviet Estonia’s central breeding interest was cattle, poultry breeding was by far the most successful in terms of maintaining a high level of production after collectivization.13 High pedigree poultry was desirable for the purposes of provisioning in that elite poultry breeding could not only produce higher quality products, but could potentially increase the amount of eggs and poultry available relative to agriculture of other states.14 In the village of Kurtna in particular, there was an important role for poultry breeding even a decade before the development of Pormeister’s architecture. Already existing in the village was a small poultry breeding station founded in 1950 that was used to breed chicken and geese, illustrating that the conversations about poultry breeding were already of significant interest to local farmers in Kurtna.15 A 1953 photograph depicts a meeting at Kurtna with multiple poultry farmers discussing best practices in terms of raising chicks or increasing the productivity of chickens.16 The Kurtna breeding station was the only elite poultry breeding farm in Estonia until 1960, though two others were established soon after.17 The role of the Kurtna kolkhoz, therefore, appears to be tied to the path dependency of the village, and also an opportunity for mechanizing and improving architecture as a means to increase agricultural output—in this case poultry products.

In tandem with the pragmatic agricultural considerations, Pormeister’s administrative building for the Kurtna Experimental Poultry Farm is illustrative of the Soviet policy aim for a mechanized agricultural industry emphasizing scientific research through the development of a new architectural typology. Only twenty-three kilometres from Tallinn, the building provided one of the first state of the art facilities for poultry research in Estonia to facilitate the development of scientific research on poultry breeding. The plan for the building included offices and laboratories for research on both floors of the building, and integrated a small scientific library and a visitors room in the second floor.18 Conference rooms, a main meeting hall, and services occupy the ground level, serving the public and administrative functions of the kolkhoz for residents.19 If we consider the imagery of the laboratory spaces of Kurtna as compared to a photo taken roughly a decade earlier showing the non-state sanctioned meeting of poultry farmers, it would seem that a dramatic turn toward framing farming as a science was an integral consideration in the program of the kolkhoz.20 For example, while in the earlier photograph from 1953 poultry breeders stand in front of a large wooden building next to geese running free in front of a large crowd, the imagery from inside the new laboratory depicts the director of the kolkhoz alongside scientists in staged photographs near scientific equipment, birds in cages, and eggs. This contrasts suggests a concerted interest from the ESSR to illustrate how architecture and a rural policy results in architecture in service of rhetoric of modern and scientific agricultural practices under socialism as opposed to the seemingly disorganized collection of private farmers. In short, the scientific rhetoric embodied in a new typology of agricultural architecture—the modern scientific research centre—is illustrative of a soviet rhetorical aim in rural architectural policy.

Even with this dramatic staging of soviet rural architecture as scientific, and by extension the collectivization of small scale architecture into large-scale productions, the efforts to increase production seem largely ineffective. While the Kurtna breeding farm was one of only a few examples of a modernized poultry breeding farm, the level of poultry production was not necessarily increased as a result of collectivizing farm architecture or scientific measures in this time. The work of farmers who maintained small plots for personal use were more successful in producing poultry goods than the large-scale agricultural facilities in this period.21 Despite the argument, therefore, by the USSR that collectivized, mechanized, and modernized agricultural activities is inherently more productive than the alternative, it would seem that this is in fact an inconclusive estimation. In fact, much of Khrushchev’s agricultural policy, particularly with respect to his aim to develop wheat farming in parts of rural Russia, were catastrophic failures.22 Also, while it may seem to be a standard for agricultural research facilities generally at this time, it by no means was common for a small village to have a dedicated research facility for farming, thus illustrating the selective and microscopic nature of interventions. It must be noted, however, that the USSR was not alone in this assumption; a shift from small-scale farming towards large-scale mechanized agriculture was occurring the world over, including in the United States where businesses were developing large farms over family farms. In the case of the United states, it was found that these arguments were largely rhetorical in that mechanizing was considered to be a fact of business though they were not necessarily more or less productive than small family farms.23 In short, despite an architecture that enforces the idea of scientific collective farming as inherently more productive than small-scale farming, this assumption is not necessarily true.

Beyond an argument for the collectivization and modernization of agricultural research through the development of centralized research centres, Khrushchev’s rural ideology is also based in the introduction of a modernist aesthetic regime. To mirror a thaw in social policies towards ones that aimed to raise living standards for Estonians from Stalin’s inhumane forced collectivization, Khrushchev also instituted a change in the design standards.24 While Stalin’s aesthetic regime was based in socialist realism which largely manifested as non-specific neoclassical buildings, Khrushchev’s socialist modernism was adopted in 1956 as a destalinization and modernisation policy.25 The content of socialist modernist buildings was primarily rooted in an interest in using the low-cost construction techniques of international style buildings, but was also an opportunity to allow for buildings that were “nationalist in form, and socialist in content.”26 International-style modernism therefore not only served as an opportunity to engage with the vogue of architectural production outside the USSR—something that would help the USSR to attain an image of modernity on the world stage—but also to allow for some regionalist aesthetic content. The benefit of regionalism was not only to take advantage of a slight decentralization of architectural labour, but also to allow for more formal flexibility and in some ways to appease occupied countries’ desire for national expression. While the mitigation of nationalist content of buildings was not necessarily clear, Khrushchev’s aesthetic policy certainly enabled more architectural freedom than in the Stalinist era, particularly in rural areas.

The liberalization of aesthetic ideology combined with the sheer scale of the project of implementing a rural policy focused on development is exemplified in the change in bureaucratic structure managing the construction of kolkhoz projects. It became rapidly apparent that it was impossible for a centrally managed government in Moscow to design for all situations in rural areas and ensure that the construction labour would be sufficient to produce buildings in light of Khrushchev’s development-centric rural policy. The design work was therefore logically placed in the hands of the nations, where in Estonia, for example, a state office for the construction of rural architecture was for all intents and purposed in control of the designs of collective farms. In Estonia, however, this state office was eventually undermined through a separate bureaucratic development. In Estonia, many kolkhozes formed regional and eventually national building companies called the Kolhooside Ehituskontor (KEK)—Construction Office of the Collective Farms. KEKs built for a greater profit once they became more established as a precedent, and therefore had more ability to hire and retain skilled construction workers for building projects on collective farms. These KEKs were thoroughly ingrained in the fabrics of the various regions they worked in, however, and eventually it was decided to develop the EKE Projekt which developed architectural designs for each of the KEKs. Because of this institutional distance, the collective farms had a great deal of liberty to construct whatever work they pleased, making the EKE Projekt the locale for more experimental works of soviet architecture than any other space.27

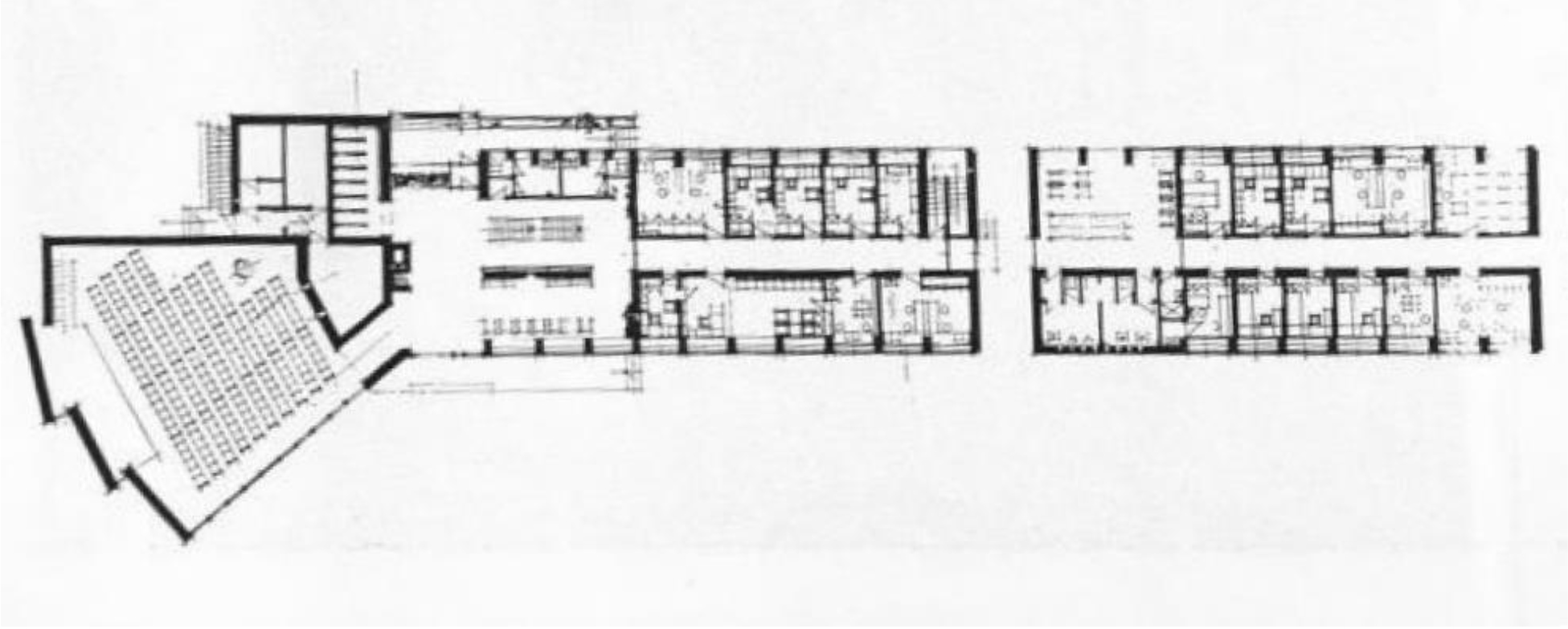

Ground Floor Plan of the Kurtna kolkhoz administration building.52

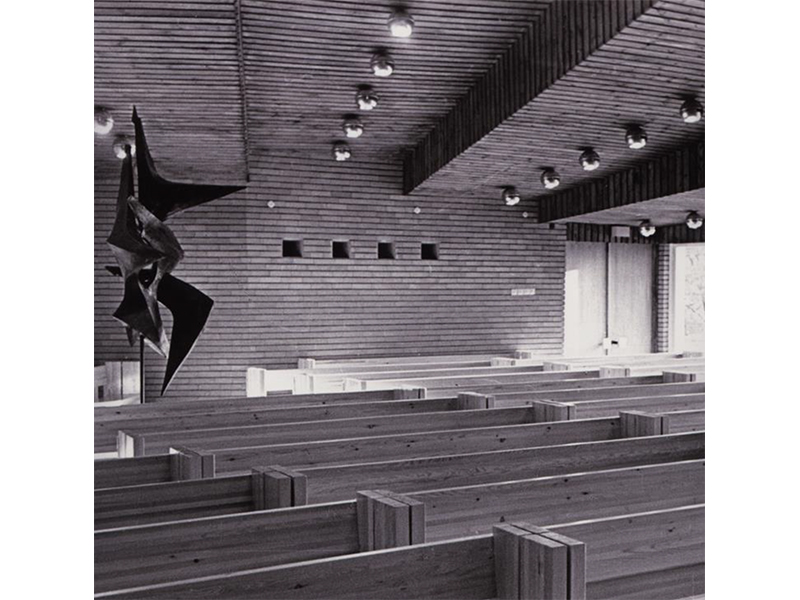

The architect of the Kurtna kolkhoz, Valve Pormeister, was therefore at much greater liberty to produce a more thoughtful and expensive architectural project for the administration building than most other collectives, which contributed to the high quality design of the project as a result. 28The lack of regulation, liberalizing of style, and support for attracting skilled workers created a perfect storm for architectural experimentation in the countryside, which resulted in the development of the administrative building at Kurtna that was architecturally unlike many buildings in Estonia and the USSR. Beyond the framing of the work as a scientific project through the planning of laboratory and office space, the detailing of the project was highly celebrated, and the project was used as an example of fantastic soviet architecture not only in Estonia, but across the USSR. The assembly hall was particularly spectacular, as it fanned out from the bar of office spaces into a large, wood-lined space that strongly resembled Alvar Aalto’s churches.29 The project also included elegant designs for stairs, where the side-entry stairs to the upper floors appear to float from the brick façade, and also included elaborate mosaics completed by an interior designer.30 The project was so spectacular compared to most rural works that it received a full spread in the pages of the French magazine Architecture d’aujourd’hui in 1970, which commended its elegant and simple design that complemented the rural landscape, all the while making small but dramatic architectural decisions to create a good project. In short, the liberty offered by the EKE Projekt enabled Pormeister to develop a building that deviated from the less playful work of state architects that was highly celebrated.

The celebration of the project on the international stage, however, signals the success of Khrushchev’s aesthetic policy on a broader scale beyond the lack of control of the KEK that enabled the construction of an expensive and not necessarily socialist project. The inclusion of the project in Architecture d”aujourd’hui signals an opportunity for the USSR, at this point under the leadership of Leonid Brezhnev who largely continued Khrushchev’s aesthetic policies, to use Estonian work as propagandic content for the success of rural soviet industry. While the intent of Pormeister, a celebrated Estonian architect, was not to produce a marketable piece of architectural propaganda, the values it embodied in terms of architectural ambition and scientific ideals served as the perfect opportunity for propagandic content. Overall, while not detracting from the merits of Pormeister’s design, the USSR was ultimately able to weaponize architecture that was developed with nationalist content as a tool for propaganda.

The project’s considerate landscape design is an example of the tension between Pormeister’s integration of the work into the Estonian landscape, but also of the interest in soviet control of rural land. Pormeister, trained as a landscape architect, includes a man-made pond in the ground level of the project due to irrigation issues in the site. The building, which lies low to the ground, looks over the pond which is placed between existing lakes on the site.31 It would seem apparently that Pormeister’s delicate inclusion of the man-made lake blending into the landscape of the village and Harju county would be a pure manifestation of integrating the project into the Estonian nation. However, it might also can be seen as soviet control of nature, not only through the controlled breeding of poultry that pass through the farm as a tool for provisioning markets, but also a tangible ecological intervention into the fabric of the landscape of the Estonian countryside through the excavation of land. The dichotomy and tension between the expression of Estonian identity and soviet policy and control thus become illustrated in the landscape design of Kurtna’s administration building.32

The Kurtna kolkhoz in 1966 pictured from the street.53

The continued tension between Estonian architectural heritage and soviet policy is evidenced in the changes to land ownership policies in the post-soviet era. After the fall of the USSR in 1991, and even slightly before in Estonia with the 1989 Farm Law, the ownership structure of rural land was entirely reversed. The Farm Law first enabled structural changes by legalizing the creation of private farms for new farmers, and struck the requirement to join collectives.33 The development of this policy was one of the many catalysts that pushed the ESSR and eventually the USSR to dissolve in 1991 because it attacked the fundamental ideals of the Soviet Union’s policy. The dissolution of collective farms, however, began in earnest with the Land Reform Act (1992) and the Agricultural Reform Act (1996) which both set in motion processes to return all collectivized rural land to the previous owners.34 The Land Reform Act involved an extremely complex restitution process: when land was restituted it was first offered to the landowners from 1940 or their rightful heirs, and if no offer was made was placed on the market for private purchases or remained in the state’s possession.35 In terms of agricultural land, the number of agricultural holdings dramatically changed in the wave of privatization that occurred; while in 1989 there were 1,154 agricultural holdings, this jumped to 55,748 in 2001.36 In short the abrupt reversal of land ownership from a collective to a private model had concerted effects on the agricultural land and the potential for farming activity across the country.

Beyond land ownership, land restitution policies had a dramatic effect on the agricultural industry in Estonia because of a limited capacity for large-scale farming, as well as the turn toward a free-market economy. Between 1992 and 2000, agriculture as a share in Estonia’s Gross Domestic Product feel from 11.76% to 3.6% and is the result of many factors pertaining to knee-jerk post- soviet policy.37 With respect to land restitution, the result for agricultural production in the Estonian countryside was therefore dramatic; because tracts had been so deeply fragmented, land that was restituted became insufficient to support contemporary farming practices.38 In the period immediately following the fall of the USSR, also, the trade agreements that had been established with the Leningrad region also collapsed and heavy tariffs were implemented by Russia limiting the market for Estonian agricultural products.39 Most importantly, however, the dramatic turn toward a neoliberal, market-based economy in a short period of time did not allow for small farms to survive such a large structural shift.40 With the collapse of a market for agricultural goods in tandem with a reduction in the ability to use rural land for modernized farming practices, the agriculture industry in Estonia took a severe blow in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the USSR.

The consequences of these changes for collective farms was dramatic. After the immediate effects of land restitution and agricultural policy change, number of farms and land ownership of rural land shifted and stabilized into a more sustainable model of large private farms. For example, while there were 55,748 agricultural holdings in 2001, this number dropped to 16,079 by 2016.41 This shift in the number of farms is correlated to an overall increase in the average farm size, where the number of farms with more than 50 hectares has increased and all smaller farm sizes has significantly decreased.42 Despite this stabilization in terms of agricultural plot size and ostensibly a concomitant stabilization of productive capacity of farms in recent years, the rural population was severely fluctuating and overall saw a large reduction in rural dwellers.43 Therefore, even in light of stabilization, because of a dramatic decrease in agricultural production immediately following the fall of the USSR and the resulting reduction in the rural population, most collective farms were abandoned in the early 1990s.44

While some collective farms had celebrated architectural heritage, the resulting consequence of a decrease in rural population, a lack of agricultural productive capacity, and the association of the heritage to the USSR’s policy meant that many fell into disrepair. While some obtained new life as shops, warehouses, or municipal buildings, many are left with limited maintenance because of their painful association with collectivization and the USSR.45 Overall, the programs of the buildings have been largely transient as compared to their original intended use. The association of the USSR’s policies that forcibly collectivized with the architecture of collective farms therefore appears to be, despite a renewed interest in the productive capacity of larger farms, too controversial in its implications in most cases.

In the case of the Kurtna kolkhoz administration building, it is one of few collective farms in Estonia to obtain new life in the post-socialist era, and one of even fewer collective farm administration buildings to be added to the national heritage register in 2001.46 In the years after the fall, the Kurtna administration building was abandoned for over a decade. After its designation as a national monument it was retrofitted as a hotel in the early 2000s and has since become a conference and events center.47 The events centre—Kurtna Sündmuskeskus— opened under new management in 2017, and largely hosts weddings and parties. The website of the events centre offers no reference to the building’s historical background.48 The success of the Kurtna kolhoz in its continued use and preservation is not the norm, however, and its ability to be reused is likely because of its proximity to Tallinn by car as well as its architectural merit that continues to make it marketable for new functions. In short, Kurtna offers a rare example of a somewhat successful preservation of the administrative buildings of rural kolkoz architecture purely based on its ability to turn profit through its desirability, though this example is not the norm.

Valve Pormeister’s Kurtna kolkhoz thus offers an insight into the politics of built heritage as it pertains to shifting landownership, agricultural, and aesthetic heritage in Soviet Estonia. Collective farm architecture in Estonia offers on the one hand a picture of the socialist ideals to modernize and develop a scientific narrative for agricultural industry, and to ensure productive capacity for the provisioning of a large territory. This narrative also includes an emphasis on the role of architecture and urban planning to exemplify these ideals into aesthetically well-executed projects. On the other hand, the picture of collective farm architecture in Soviet Estonia is illustrative of the myopic vision of not only the USSR’s socialist policies, but also the lack of clear post-socialist policy in agriculture that both left the agricultural industry in a state of disarray. The continued use and preservation of socialist built heritage is therefore as much in flux as Estonia’s 20th century political history; to retain these sites of important agricultural production not only as emblems of forced collectivization but also of Estonian architectural ambition, a framework emphasizing the retrofitting of potential sites for continued use is necessary.