A matter of stance

Adriano Niel

With the Modern Movement’s decay, architecture was plunged into an aura of anguish and negativity, centered around the failure of a rational order in organizing the modern world and the consequent loss of a system of values and rules capable of anchoring architectonic production. The non-existence of that universal code of values made inevitable the […]

With the Modern Movement’s decay, architecture was plunged into an aura of anguish and negativity, centered around the failure of a rational order in organizing the modern world and the consequent loss of a system of values and rules capable of anchoring architectonic production. The non-existence of that universal code of values made inevitable the need for some authors to initiate the search for a personal code of values that can define their approach. This fact became too evident in the second half of the XX century, when the search for construction – both physical and theoretical – of a new ethos would become central to the post-modernist architectonic discourse.

The growing settling of a never-ending multitude of approaches and ideologies we’ve inherited from the post-modernist period makes it relevant to look at the subject’s progress, from the viewpoint of a confrontation of stances. The famous and exciting debate between Peter Eisenman and Léon Krier in the late XX century serves as premise for a dichotomic reflection on how to face progress that is built upon a confrontation of ideologies between four cornerstone figures of contemporary architecture. When their works are counterpointed and their paradoxes revealed, Peter Eisenman, Léon Krier, Glen Murcutt and Rem Koolhaas are amongst the contemporary architects that best represent the idea that facing the future is merely a matter of stance.

TECHNOCENTRISM / ANTHROPOCENTRISM

The bedrock changes on civilization triggered by scientific and technological breakthroughs that characterize the modern times drives taking a dichotomous stance on how to face the future related to our vision of our cosmic condition. The classical idea of the man as the center of Space present in the origin of the history of art and architecture has reached its maximum expression during the Renaissance period, with the invention of one-point perspective. This anthropocentric model would come to be gradually discarded since the Copernican revolution of the XVIIth century, when the Cartesian method as the cornerstone of analytical thought, the Newtonian laws and definition of an immutable Space, absolute and abstract, produced a mechanistic view of the Universe, completely reforming the foundations of civilization. This new paradigm would become the theoretical core of the modern movement, based on functionalist and mechanist logic. Nevertheless, with its end and the discredit of its values, the architects of the Vanguard found themselves having to rethink the roles of Man and Machine in defining their new paradigms. Eisenman explains that man has traditionally defined himself in a cosmic triad, composed by Man, God and Nature, assuming three different stances: theocentrism (God as mediator), anthropocentrism (Man as mediator) and, lastly, biocentrism (Nature as mediator). However, he defends that, considering the current potential for civilization’s nuclear destruction, a technocentric objective exists in which external forces that are out of humanity’s control have assumed a position in the system, making it impossible to return to an anthropocentric view and constantly forcing us to react to new limits. On the other hand, Krier supports the idea that innovation should be passed down through generations and tested by time in a process of sedimentation. The fundamental aesthetic and ethical values should be considered as universal values that transcend Time and Space 1. Starting out from the attack against modernist ideas, still impregnated with contemporaneity, he sustains that, in our necessarily anthropocentric conception of time, Nature’s typological inventory is invariable and should be the basis of any human conception. While Eisenman’s anti-humanism deals with the disappearance of the heroic figure of the Vitruvian man as the center of Space, Krier seeks to rebuild a classical humanism, based on notions of stability and continuity, assuming man as the central figure.

CONTEMPORARY METHOD / TRADITIONAL METHOD

Technological innovations triggered by the industrial revolution would come to transform the very notion of Space and Time. Recurrently, the masters of Modernism manifested their ambition to work beyond borders. Le Corbusier, Mies Van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn made it their permanent quest, travelling in order to understand and investigate in loco, as well as to expose and impose their architecture. In this way, the architectonic method reflected a necessity to know the site, stropped in the Beaux-Arts tradition: drawing as an instrument of observation, investigation and knowledge. In the second half of the XXth century, as communication technologies developed and became widespread, reality would transform itself more intensely, bringing about an evolution in digital software that foreshadowed the direct transposition of imagination unto the physical/virtual form, in a sort of fantastical bypass2. The fascination with the new digital media, the pressure from capitalist markets and the reduction in production time would lead to a mutation on the perception, conception and construction creative methods in architecture.

In an attempt to keep up with evolutions in the subject, Rem Koolhaas introduced new methodological processes. One of them is the diagram, a replacement for traditional representation models. In a way, it accompanies the transfer of the architectural commission from public to private domain, from state to the corporate world. Research/analysis is another such process, becoming essential for the success of his production in his work: the creation of AMO proves it. The interest in data collecting in Koolhaas breaks out in the incessant production of writings on urban realities that precede the projectual inclination. The diagram took drawing’s place as a communication method, while research/analysis replaced drawing as a method of perceiving spaces. In an antagonic perspective, Glenn Murcutt’s practice is consolidated in two traditional methodological processes. The first being the drawing, the connection between imagination and the hand, as a method which is transverse to all project phases. Juhani Pallasmaa mentions that, in their embryonic stage, Murcutt’s drawings are croquis with quick notes that capture the basic schema and the dynamics relative to the place whereas, in its development phase, detailed drawing is perceived as a creational process3. Murcutt’s take is that «to draw is to reveal; to reveal is to understand; to understand is to begin to know»4. He draws by hand and admits his skepticism regarding the extensive and uncritical use of new technologies as a process. Mimesis is another methodological process. Regarded as a sedimentation of his architecture’s basic principles, it reflects a search spread out through time, by observing Nature and the drawing itself as a means for knowledge. Amongst his initial works like the Marie Short house (1975), and the more recent works, such as the Mount Wilson house (2008), there is a mimetic perfecting of the same solutions as a synthesis for his foundations. If in Koolhaas’ work the contemporary method reflects his condition as a slave of Time, the traditional method in Murcutt’s work exposes him as a manipulator of his own time. This two antagonic stances towards the severe mutations on the way architecture method in contemporary times is understood represent the idea that, regardless of the difference between scale, type and complexity of their work, there’s a kind of a personal code of values and rules that precede and measures their ambition.

The well-known text by Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia”, explains that, in the face of losing someone, something or an ideal there are two types of emotional extrapolation that can manifest themselves: mourning and melancholia. The difference resides in the fact that melancholy is connected to the loss of an object that is unconsciously maintained, which is to say that one knows what he has lost but not what he lost in that “someone”; mourning is connected to the conscious loss of an object, which would imply someone’s capacity to become autonomous with respect to that loss. This text will certainly have some form of correlation with processes due to postmodernist approaches. While reacting to the loss that represented the Modern Movement’s decadence, some architects have positioned themselves as searching for the return to bygone ideals, whereas others have understood its bottom line and looked for formal autonomy.

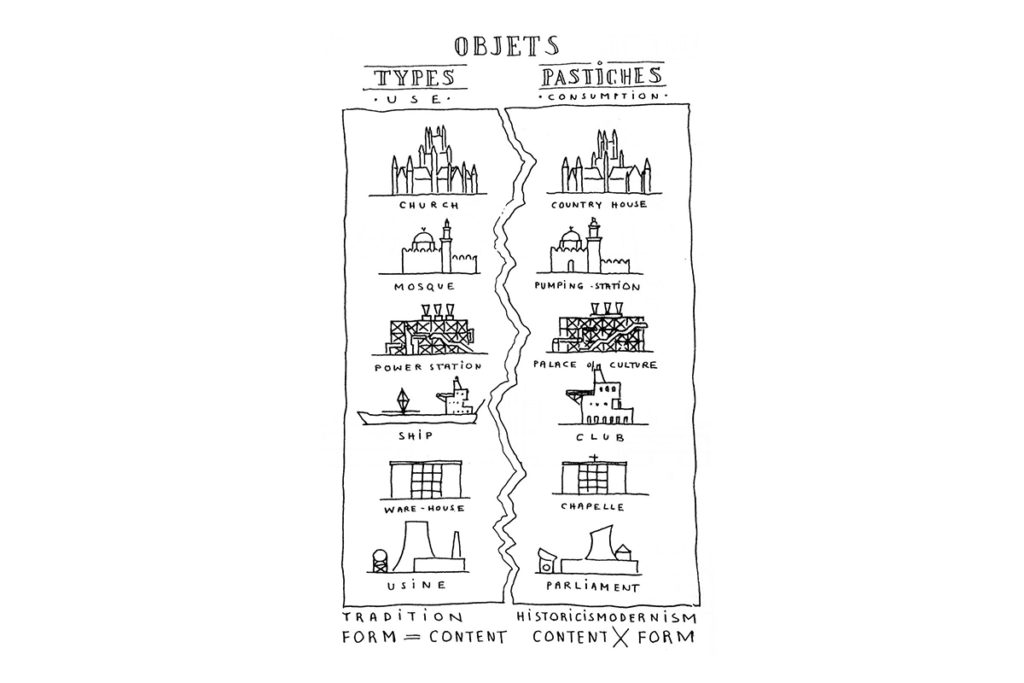

Figures such as Aldo Rossi, Christopher Alexander, Demetri Porphyrios, Léon Krier or Glenn Murcutt, whose discourse centers itself in a vision of the future through a melancholic interpretation of the past, would fit in a kind of doctrine of melancholy. As mentioned by Freud, melancholy’s characteristic traits are the decrease of self-esteem, a heavy discouragement or a disinterest for the world that external to his ego. Krier makes this clear. The numerous sketches comparing the classic era and the modern world, praising the former and incriminating the latter, bear a form of anguish, discouragement and disinterest for the modern world.

Characters such as Daniel Libeskind, Bernard Tschumi, Zaha Hadid, Peter Eisenmanor Rem Koolhaas, whose approach is built on a grief-stricken search for the subject’s autonomy towards its own progress, would then fall under the doctrine of mourning. There is a clear conscience of loss and of that which it means, which in turn leads to giving up what that loss represents. Grief makes giving up the object compulsory by offering the ego an incentive to go on living. Koolhaas is perhaps the best agent of this doctrine. He understands early on the Modern Movement’s failure and looks to overcome this loss by adapting to the vicissitudes of contemporaneity. As someone who is “grief-stricken”, despite accomplishing autonomy when it comes to loss, he still denounces the negative trend in which the subject proceeds. Writings such as Junkspace or Generic city are paradigmatic examples of that.

If melancholy refers to an incapacity in untethering the past from present and future, then mourning concerns an acceptance of losing and the search of new autonomous paths that may lead to values that have faded. Whether one takes a more melancholic or a more mournful approach towards the subject, progress will always remain a matter of stance.

1 KRIER, Léon in “Architecture: Choice or Fate”: 47

2 KOOLHAAS, Rem in “The Smart Landscape: Intelligent Architecture”, «https://artforum.com/inprint/id=50735»

3 Juhani Pallasmaa – ‘Plumas de Metal’ in EL CROQUIS in “El Croquis 163/164: Glenn Murcutt 1980-2012”:39

4 LEPLASTRIER, Richard; MURCUTT, Glenn – Glenn Murcutt and Richard Leplastrier in conversation (1:22:34), Architecture Foundation Australia, University of Newcastle, 2014, «https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ESYEENgUGA»

Adriano Niel (Lisboa, Portugal, 1992) is a Lisbon-based architect, researcher and writer beginner. Graduated in 2016 from FAUL, Faculty of Architecture from University of Lisbon, with a master thesis focused on the role of international architecture in the city of Luanda and the antinomies of its progress. Currently working at Aires Mateus. Also collaborates with different architects in several private architecture projects and competitions.