(Fake) News from Nowhere – Utopia against stagnation

Julia Dorn

We are finding ourselves in the age of the Anthropocene, a time and space in which the human habitat is so encompassing that traces of our impact can be found in the most distant places and unlikely scenarios. It is overdue then, that we, as individuals and as a society, need to take responsibility in […]

We are finding ourselves in the age of the Anthropocene, a time and space in which the human habitat is so encompassing that traces of our impact can be found in the most distant places and unlikely scenarios. It is overdue then, that we, as individuals and as a society, need to take responsibility in redefining these traces. We have been deprived of our faith in progress when realizing that all technological achievement comes at a cost, and resignation spreads. Understanding that there is not one holistic solution to all challenges, often utopian aspirations are demonized as blue-eyed and instead self-limitation is an overarching quick-fix. What does the way out of this self-imposed stalemate situation look like? How does society negotiate between collective action and collective agendas? What role does the positive element, a notion that is inherent to Utopian thinking, play for society’s understanding of resistance and common striving? Do Utopias exist, and what are their current constructions?

Any Utopia can only evolve from the present, in that it is created. Thus Utopian thinking reveals the substantive conditions of the present and its reflection helps to formulate wishes for the future. Depending on how this relationship between present and future is negotiated and what is declared as ideal, implications on power arise that define social development. These implications are, among other things, determined differently in various attempts at defining “Utopia”.

INHERITED CATEGORIES OF UTOPIA

One idea of Utopia is the hopeful thinking of the desirable, but the space of possibilities that allows one to achieve their desires is not yet given1. Consequently, this type of Utopia imagines a future without elaborating on the realization methods. To eliminate common reflection on the obvious lack of these realization methods, simplification is an inherent aspect. Therefore, it is prevalently engaged in the language of populist politics, where the negotiation of alternative truths is sabotaged with “fake news”. As this approach often leads to societal manipulation and results in an abuse of power and public sovereignty, it gives meaning to the negativity surrounding “utopic” ideas. Yet, as it can be investigated in populist camps, this approach can generate an enormous captivating drive, and in turn celebrates strong positivism on an individual level as a general and universal concept of the future.

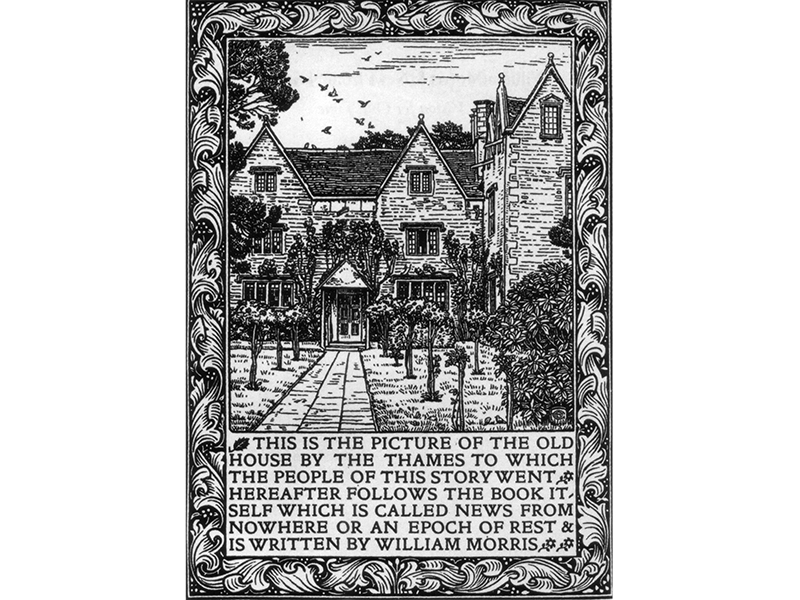

Contrasting this populist ideology, Early Socialism Utopias precisely construct a distant time or space in detail. Hereby, certain ideals and principles function as coordinates. These Utopias conceive an ostensibly more successful holistic system. Due to the detachment of current circumstances, these Utopias bear the potential of great inventions as the space of possibilities seem endless – ultimately a positivist approach. Yet, by striving for social cohesion, these Utopias tend to create a rigid system. Early utopists like Morus or Fourier underestimated the notion of authority neglecting that the total principle of personal wellbeing finally manifests as an imperative implying a forceful form of civic solidarity2. Often understood as a tool to integrate social cohesion into planning, many urban Utopias claim to paint the “ideal city”. It is “erected on new, virginal ground. They elide what Rem Koolhaas once evocatively called “junkspace”—the accumulated layers of (built) environments, weathered, eroded, and transformed by time, by usage, by life”3. While in modernity, the ideal city was of functional division and car-oriented planning, today’s “Smart Urbanity” is eager to erase friction and provide an Instagrammable Utopia. Problematic examples of ideal cities include Pruitt-Igoe, the “Google Sidewalk Labs” in Toronto and on a political level, Eastern Europe’s liberal Utopias.

Adorno opposes these painted Utopias with his “Bilderverbot” by drawing parallels to the testamentary ban of depicting the absolute and criticising the prediction of the future in a static condition of perfection as a prevailing act. His counterproposal is the relentless critique of the present as the only way to draw the contours of a pictureless future4. Here “utopia” doesn’t represent a distant time or space in the future but advocates for a processually utopian practice. By the critical analysis of current conditions, so-called “transformative elements” are detected5. This Utopia isn’t static in the Eschatologic sense, but functions as a self-assessment tool of the present and ensures that any change imagined is system-inherent, not superimposed. Yet, to understand the persistent reflection on the present as the foundation of systemic change, all inventive freedom that bears disruptive ideas is abolished, and at best a counter practice ex negativo evolves. This often manifests in a vortex of the same problems and provides no solutions. Looking at Christiania in Copenhagen, many positive aspects of an everyday egalitarian praxis of a lived utopia has fostered the idea of a slow city6. While replicating “Arcadian” ideas as found in Fouriers Phalanstère, the “Provos” – countercultural provocateurs – practice of opposing the establishment was in the end overridden by international tourism. To take it even further, counter practice itself becomes repressive when it loses its liberating and enlightening element through its establishment. Bini Adamczak attributes the failing of former revolutions to the lack of sufficient Utopias in her book “Beziehungsweise Revolution” and shows how insufficient societal ideations inevitably cause repression.

UTOPIAN ASPECTS DISSOLVED IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY

When investigating the present, as Adorno suggests, one will understand how many significant aspects of these utopic categories are already deeply embedded in society: manipulation by structural simplification; a static “social cohesion” in illusory liberalism of the free market economy becoming an imperative; as well the desperate call for a restrictive reglementation as counter-practice and as the only solution to cope with climate change.

Isn’t it contradictory, that despite this clear integration of utopian thinking, the public discourse equates utopic thinking as too greedy in its constant hunger for progress? This results in a fear of dreaming, knowing that any kind of depicted positive image of the future won’t be any holistic enough to take on the argument of presumption. The resulting abeyance of any Utopia is perpetuated by the feeling of “having nowhere to land”, as described by Bruno Latour. “The plane that has nowhere to land”, represents our society, that departed in the 20th century with the fundamental belief in technological progress. During the flight, there emerges the realization that this belief is leading to an unrestrained environment of exploitation that accelerated climate change perpetuated by a neoliberal economy7 – a circumstance that inevitably abolished society’s trust in the potentials of technology8. Yet, in a context that stigmatises technical progress as insufficient and strives to restrain progress as a consequence, any efforts are not progressive but reactionary and the discourse stagnates. Today the only concepts which offer a way out of the crisis are self-limitation and preservation, including strategies like efficiency improvements, impact offsetting and single-resource approaches9. But the self-limiting aspect in fact diminishes the space of possible solutions extensively.

SO WHY DOES SOCIETY NEEDS UTOPIAS?

Today every individual’s personal relation to future is prevailingly determined by utopias and dystopias conceived in pop culture and in the media. How can we shift that passive role of the individual, who is fed with mostly dystopian images, towards an active role of consciously imagining Utopia? Bloch’s conscious theory-practice describes the future as the unaffiliated space of possibilities and on the assumption of the incompleteness of being, it equates hope to dissatisfaction, to a “No to deficiency”. Only every individual’s conscious and active imagining of this unclosed space can mean progress towards the future. This concept is “The principle of hope”, in that the principle itself becomes imperative for every individual10.

Critiquing current systems bears the potential of infiltrating them. To avoid the way into repression and desperation, an emancipative striving prepares an alternative concept: one that is pieced together by individual actions. For contemporary Utopia this implies fragmentation, yet normativity, as these active fragments should be directed towards a quest for improvement. How can Utopia do justice to the claim of, on the one hand, actively changing the current material conditions of society and, at the same time, integrating the aspect of the positive and innovative? What would a Utopian movement look like today instead of a Utopia that merely stands for a future social form?

ACTIVE PROGRESS FOR UTOPIA

Returning to Bruno Latour’s allegory, the negative connotation of technical achievement faces another aspect. Current technology – somehow based on rationality – has reached an immense complexity, obvious specifically in Artificial Intelligence. Although society considers itself to be in the age of rational humanism, it is humanism, that implies, how complexity naturally provokes a counter movement towards oversimplification and one-dimensional answers, sometimes of a mythical, sometimes of a populist manner.

From here we can unfold the narrative of our seemingly desperate situation. With the deprivation of faith in technology, the space of possibilities for Utopia was closed. Yet can a new understanding of progress restore our confidence?

Having this in mind, it is now important to think of the role AI plays in social organization. AI-enhanced projects are exponentially designed and have no defined goal as they exist outside of our cognitive limits. Consequently, the vertical movement, that describes “progress”, is now extended by a horizontal direction, and not only is the space of possibilities seemingly infinite but also the space of solutions.

Embracing, rather than abolishing this relation makes progress the missing link that opens up the possibility space for Utopia. Progressive Utopia is fragmented as it will find ways to achieve one or more solutions for a specific system-inherent problem. This dissolves the critique Adorno and others imposed on early Utopists that depicted a coherent future with one prevailing method and solution to solve a multiplicity of problems. Instead Progress is an active cycle of inventing, testing, reviewing and adopting hypotheses, and therefore becomes a current and active utopian practice itself. Almost never reaching the point of satisfaction, progressive Utopia is normative in the way it unites an insatiable will to change with an unalterable positivism.

A PLAIDOYER

Are we in an egoistic society of consume-driven individuals that are deprived of the belief in progress, incessantly romanticizing the past, all the while crucifying hedonism and married to the idea of self-limitation as the answer to cope with crisis? To establish an alternative system that allows for an “improved” future, perhaps we can overcome these contradictions by uniting divergent, but positive, aspirations. The type of Utopia we now are projecting must restore faith in (technological) progress as a playground for ideas, inventions and concepts, because only progress as such can create an active environment of interdependent individuals striving for change, the endpoint not carved in stone but a web of possibilities.

I am advocating for losing our fear of available tools and actively making use of them instead of our unconscious submission to them. Moreover, for uncompromisingly questioning resentments we carry against technological aspects due to a seemingly moral superiority. I am arguing for the unconditional desire to change, to stop the perception of mankind dissolving in crisis and to restore the courage to dream of Utopia.

1 Key note by Martin Fries: Bildergebot – Utopie als notwendige Denkanstrengung

2 de Bruyn, G., Die Diktatur der Philanthropen. Entwicklung der Stadtplanung aus dem utopischen Denken. Braunschweig/Wiesbaden: Bauwelt Fundamente. 1996.

3 Saadia, N., How ‘Blade Runner’ and Sci-Fi Made Everything Dystopian, CityLab. 2019.

4 Truskolaski, S., Bilderverbot: Adorno and the Ban on Images. Doctoral Thesis. 2016.

5 Dornick, S., Auf dem Weg zur utopischen Gesellschaft – Relationalität bei Judith Butler, Sara Ahmed und Édouard Glissant. Femina Politica – Zeitschrift für feministische Politikwissenschaft, 2019. pp. 46-58.

6 Saadia, N., Ibid.

7Latour, B., Das terrestrische Manifest. Berlin: Shurkamp. 2017.

8Freund, N., Das Ende ist nah. Süddeutsche Zeitung, Issue 05. Mai 2019.

9Brugmann, J. & De Flander, K., Pressure-Point Strategy: Leverages for Urban. sustainability. 2017.

10Bloch, E., Das Prinzip Hoffnung. Werkausgabe: Band 5 Hrsg. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. 1985.

Julia Dorn studied Architecture and Urban Design in Vienna and Berlin. Since the implications of an interwoven architectural and cultural landscape are of a special interest to her research, she focuses on the interplay between the discourse and its public reception. Beside being part of various exhibition projects recently, she currently works for CHORA Conscious City, Chair for Sustainable Planning and Urban Design, TU Berlin as well as Smart City | DB. She found her curiosity for Utopias in a seminar on “Alternative Truths and Fragmented Utopias”.