When Venturi met a Bolivian alchemist

Lemonot

“[…]I am trying to find a sort of hybridization that oscillates between biomedicine, which I consider traditional and popular medicine, the antithesis of it. The best result is in using both. F. & A. Escobar “When circumstances defy order, order should bend or break: anomalies and uncertainties give validity to architecture.” R. Venturi Cliza is […]

“[…]I am trying to find a sort of hybridization that oscillates between biomedicine, which I consider traditional and popular medicine, the antithesis of it. The best result is in using both.

F. & A. Escobar

“When circumstances defy order, order should bend or break: anomalies and uncertainties give validity to architecture.”

R. Venturi

Cliza is just a few kilometers away from Cochabamba, one of the main cities of the central part of Bolivia. It is a very quiet town, in the middle of nowhere, mostly known for its famous “Pichon a la brasa” and delicious “anticucho”. For us, however, going to Clizia became an obsession. Everything started from one single snapshot found accidentally on google maps while we were in La Paz investigating the phenomenon of cholets. Almost by chance, digging into the digital universe of google, looking for other examples of Andean architecture, we landed within the deserted roads of Cliza.

The town had the classic characteristics of any Bolivian suburb; a great industriousness in the agricultural field and a strong identity in folkloristic everyday rituals. These places nowadays are a fertile ground for the rising of cholets, usually constructed by wealthy families who every weekend host grand parties, whether religious or not, to gain respect but often arousing also jealousies inside the community. Cholets are now a privileged architectural translation of cultural identity in Bolivia: facades of bright colours, populated by over-decorated interiors – where the kitsch meets the aesthetic rigour, profane and sacred features come together.

Therefore, we digitally unloaded the yellow little man to the gates of Cochabamba, freely discovering the surroundings from our screen view. There weren’t as many cholets as we expected, but we decided to keep walking further – eventually bumping into the “Cementerio de Toco”, just along the main road of the small town of Cliza. At the beginning, it looked as any ordinary cemetery, but then, turning around a cholita passing by, a white weirdly shaped building suddenly appeared, hidden behind a voluminous tree. From the small snapshot it could not be deducted if it had been built recently, but surely it was something that did not seem to belong to that context.

Or, actually, it was truly something that we are used to see in Bolivia, maybe pushed a bit more towards a peculiar extravagance: insertions of different styles mixing indigenous references with postmodern, post punk or even Chinese fragments. In these rural Bolivian communities, unconventional ornaments are employed both to represent the rising of collective identity and to differentiate individual tastes. If Adolf Loos suggested that modern man should have suppressed individuality, Bolivian are surely overturning the rules.

Cliza is seven hours of driving from La Paz. We departed early and once arrived we parked right in front of the entrance of the cemetery, where a group of old ladies including the keepers were festively eating in the near chapels. This is not unusual in this part of the world, where death is indeed seen as a continuation of life. Therefore, when a loved one passes away, the relatives are used to frequent the grave, arranging big family gatherings in the cemetery and playing songs to the dead. These happenings, together with the aesthetic value of apparently staged architectural backgrounds, contribute to give to the cemetery the atmosphere of a real populated city. Spatial performances to stage a conciliation between this life and the after life.

Although taken by the scene and fed by the people, as hyper excited architects we still tried to reach that odd white chapel, we passed hundreds of mausoleums, each family had its own private one but all of them had the same characteristics in common: a triangular gable frame, columns of all colours from shimmering orange to marmorino effect. Cement casted shapes and extravagant mouldings were intertwined with the traditional structures and mosaics of the apparently original chapels. It was indeed hard to understand if they were conceived in such a way from the beginning or if they were really re-designed through a series post modern additions. We looked at each others and we exclaimed: what a Bolivian Venturi!

In recent years, the sudden revival of some conservative design approaches – totally confined into the discipline and almost scared to engage with the outer world – led to such a deceiving linguistic and iconographical flatness within our commonly shared architectural vocabulary, that looking at these examples we felt a sense of relief: you could finally grasp the flavour of singularities, a certain aesthetic truth grounded into the different layers of subcultures.

Our concern is that within environments that value only calibrated refinement and established elegance, what is mundane and popular is often mistaken as vulgar. However, especially when expressed through folkloric icons and traditions, vulgarity finally can cease to have a negative connotation, re-gaining its etymological meaning (from Latin vulgus: “common people”): it intuitively triggers authenticity and a sense of belonging, helping to fight anorexic models and to broad the notion of beauty – even among those who are the most reluctant to accept exuberance and kitsch aesthetics.

Private Chapels

That’s undoubtedly the case of Bolivia, a place that shaped effective mechanisms to deeply connect architecture with its contemporary and stratified culture.

More than an hour later, we eventually discover the white plaster cast mausoleum spotted on google maps. The first one belonging to the “ Familia Jimenez”, had two shirtless keepers and dressed only in jeans set on both sides of a concave glass door. They looked like video game avatars, without a pre-established gender, they were the custodians of the sepulcher. Looking at the side they had wings, as some cyber fictional putti. It is in this common shared nature of the vulgar, together with its extravagance, that architecture provides a perfect basis for a contemporary notion of ornamentation. As architects, we can not help but wonder who ever build such a thing and why. But as well we need to question: what is an architectural ornament today? Whoever designed this mausoleum, wanted to define ornament not as an architectural detail, but perhaps as an adjective to life. Ornamentation as an open linguistic category, embracing a series of effective mistakes to challenge orthodoxy. Misspellings, malformations, malapropisms were there to produce unexpected and meaningful aesthetic hybrids, as within a colloquial spatial dialect. Outside of any architectural rule, these examples – through figurative instances, geometrical expressions and material qualities – trigger an intuitive empathy, framing a momentum, where popular demand intersects artistic beauty.

Jiménez Mausoleum

Jiménez Mausoleum

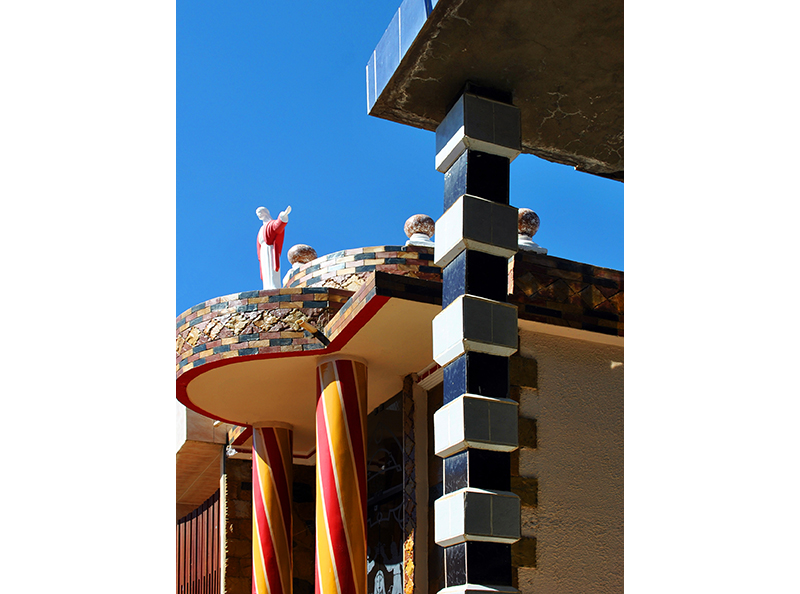

The second mausoleum built for the“ Familia Escobar” is more complex; the exterior looks like a spaceship, with a second floor that stretches the same size as one coffin. The two keepers look more like bouncers with earphones and guns at the ankles . They stand above dragon heads with longer wings and sunglasses looking down towards the viewer. Perhaps the most interesting thing is that, looking through the glass, the internal plaster grids are perfectly clean with some leaves, but totally empty – as if they are waiting for someone. In comparison to the other neighbouring mausoleums, they are extravagant but only arouse curiosity, not pain nor devotion.

Escobar Mausoleum

We should not be surprised by the eccentricity of this tomb, because funnily enough, Farid and Aldo Escobar, were specialist in their bonesetter’s clinic during the XIX century and still today they are considered the best in all of Bolivia. There are many unknown facts around their practice, because they mix scientific methodologies with popular superstitions and words of mouth. Many talks about the “Escobar manipulation” applied to herniated discs and their methodology to hybridize medical practice with secular knowledge.

We could say that Cliza is a very strange case: an experimental isolated place, where styles, identities and rituals complement each other. Going away, we stopped to see the lady who cleaned the streets of the cemetery, which did not seem to care about the aesthetics of these dwellings. Here in Cliza all of this is absurd, but absolutely ordinary.

Last night, when we were finishing to write this story, Robert Venturi passed away. We’re sure that he laughed at us writing about him in such a way, but truly we saw a bit of him in this cemetery. And, as he would have said, it definitely turned us on.