Ledoux and the (Double-)Rejection of Architectonic Language

Dennis Lagemann

I can hear the Professor, surrounded by the five orders, yelling at the abuse: Opening up his fuzzy basic concepts, he is leafing through the pages. But within the given parameters he cannot find anything to justify this aberrance. The rules of grammar are violated, everything is lost; angular columns; Did we ever see something […]

I can hear the Professor, surrounded by the five orders, yelling at the abuse: Opening up his fuzzy basic concepts, he is leafing through the pages. But within the given parameters he cannot find anything to justify this aberrance. The rules of grammar are violated, everything is lost; angular columns; Did we ever see something so ridiculous? The doctrine`s position is under attack, defending its ramparts: He may well show his dispensable manifestos; his voice like thunder; but his bursts strike the unwavering walls of the Gymnasium, and fall off without damage.1

First Rejection (Of Classical Orders)

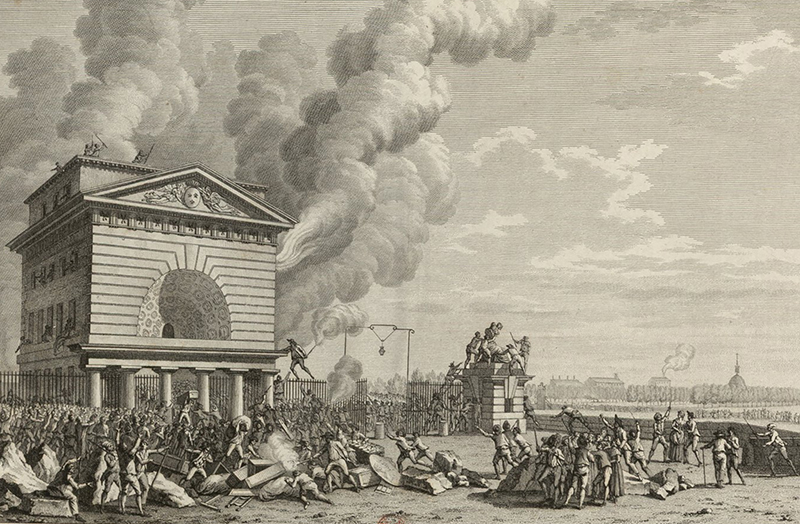

The aforementioned citation is taken from the French Revolution architect Claude Nicolas Ledoux. Convinced that architecture and society are closely linked, he rejected the Baroque identity conveyed by the classical orders as a fossilized representation of a desolate situation. His copperplate L´abri du Pauvre [Figure 1] displayed his view of the feudal regime: the pauper is left alone. Sitting under a tree, he has around him all the material available that could be turned into a comforting house. But, as an analogy to the precarious situation of the Third Estate just before the French Revolution, all that the peasant can do without the tools, knowledge of techniques, and a functional social system is to watch the gods feast in the heavens. Ledoux makes a claim that the aristocracy was more concerned about the ceremonial space of the court at Versailles than about organizing the state.

In the beginning of his career, Ledoux was involved in hydraulic engineering, 2 and as he learned that the bed of a river can willfully be shaped through stone, he was likewise persuaded that society can be shaped by Architecture 3. Bored by the superficiality and sheer beauty of Rococo, he stated that people will be barbarous or educated, depending on how they chafe at the stone surrounding them 4. And although the pre-Revolution “Building Architect” Ledoux, whose patrons were primary sponsors of the feudal system, has to be distinguished from the post-Revolution and Guillotine-wary “Paper Architect” Ledoux, his intentions to improve social conditions throughout his working life appear to be plausible. When Ledoux was working for the Duke of Montesquiou, he passionately spoke against housing peasants in sheds with thatched roofs and instead provided two storey houses with proper ventilation 5. At the same time, his designs show an intention to use architecture to railguard actions and morality, even against those who wielded authority 6.

Fig. 1

Second Rejection (From Signification to Design)

In doing away with the classical orders, Ledoux also rejected the traditional meaning of architectonic objects. To Ledoux, the temple motif was not solely reserved for sacral buildings, neither was the triumphal arch necessarily a public monument. These symbolic structures were requisites for the staging of spatial sequences 7. According to Emil Kaufmann, the term “Architecture Parlante” first appears in 1852 in an essay about the work of Ledoux, entitled “Études d’architecture en France” 8. Kaufmann states that for Ledoux, it was not the isolated samples of architectural motifs that bore symbolic content, but the syntactical combination of these motifs. Likewise, this “Speaking Architecture” did not gain meaning through reference to external content. It was the sequential setup of his “Systéme Symbolique” 9 that would objectively speak for itself when a subject is looking at or moving through his designs. To create this kind of architectural language, Ledoux primarily used three different communicative categories.

In his early career, he designed the Café Militaire [Figure 2], using naturalistic emblems to display the actual utilization of the space. Secondly, he used texture to produce an intuitively smooth or rough, homely or commanding character (Figure 3). Thirdly, and especially in his later work, he increasingly turned away from ornament, using fundamental geometric forms as basic elements of expression, associating the cube with justice and the circular hole with vigilance 10.

Fig.2

Fig.3

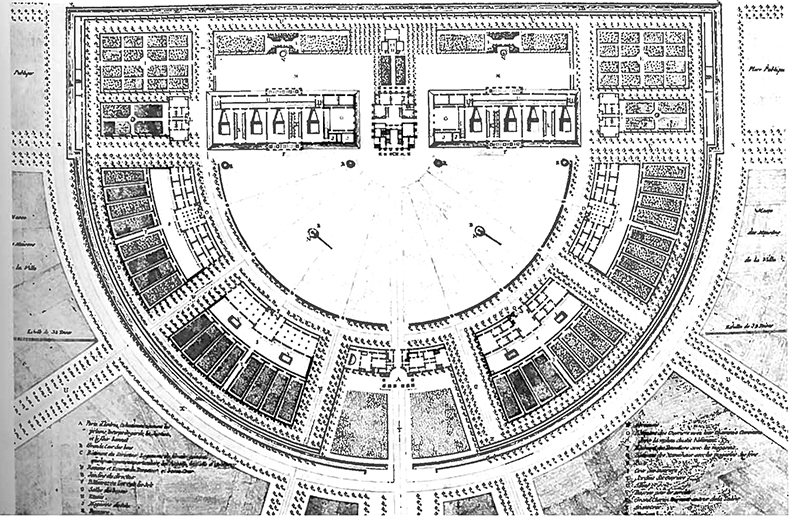

Continuing his project of creating a better society through architecture, Ledoux used the commission to design the saltworks of Arc-et-Senans as an opportunity to design an ideal space of labor. In the circular layout of the proposal, worker accommodations were arrayed around the circle’s center, occupied by the Director`s house as the source of absolute authority. The Director, however, did not reside like a lord. His house was enveloped in a cloak of fumes, oozing out of the Boiling Houses, where he was on duty to serve the community by upholding the discipline of production. Accordingly, the center of the Director`s house was a communal space of worship. In the facade’s pediment was a circular hole, watchfully overlooking the scene, indicating the Director`s vigilance and control over the facility. Ledoux’s arrangements were an attempt at social engineering, designing the saltworks as an automaton for the consolidation of morals and productivity [Figures 3 & 4].

Fig. 4

The architecture of the Saline assigned a position within the community of the saltworks to each of its members [Figure 5]. Every worker had a room for himself and his family. Four families always shared a kitchen and were grouped according to their assignment within the saltworks: the salt-cookers, to keep the fires burning, the salt-workers to process the crystallized salt, the boiler-makers to forge and maintain the kettles and even the janitor and the guards. Each of them resided the same distance from the facility center next to their working places. Each inhabitant had a garden as compensation for low wages, as well as to keep the worker and his family engaged after working hours. By rejecting the convention that only the administrative buildings were deserving of architectural articulation, Ledoux was constructing a new moral identity of community and social control through the architectonics of the saltworks.

Fig.5

Third Rejection (Vive la Révolution)

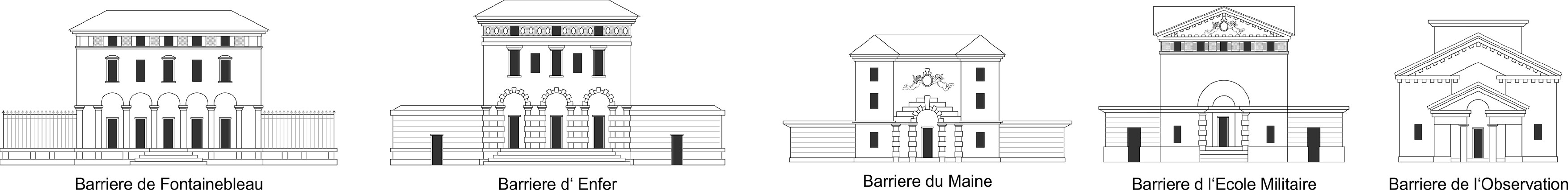

This attitude of Ledoux—that the architect was a social engineer—may have contributed to his fall from favor. In 1784, Louis XVI commissioned a wall around Paris. Taxes had to be paid to the Ferme Générale on goods being brought into the city. But because the city was open to the periphery, tax collection was almost impossible to control. So controversially, the wall was not directed against a threat from the outside but was in fact built to control the city’s own population. When Ledoux was charged with the design for the gates, he found justification in believing that the wall was built to enforce the law, which would consequently uphold the morality of the city. He conceived the toll gates as showpieces for Paris and claimed to place “glorious trophies of victory at the closed gates” 11. Accordingly, he chose to refer to the front buildings of the Acropolis in Athens, calling the gate houses “Propylées” instead of “Barriéres”, as they were termed officially.

Fig.6

On the one hand, these gate houses became a masterful application of a volumetric grammar, producing fifty-four variations of the Barriéres. Because the design of the buildings followed a strict syntax and morphology, passersby could visually understand the transformational sequences between the gates 12 [Figure 6]. At the same time, these designs were a consequent implementation of his architectonic language, representing the sublimity and justice of law and order. For those who were able to decode Ledoux’s language, the “Barriére de Passy” represented a cube of justice; its two inscribed half spheres of wisdom created circular outlines on the building’s facade, speaking of vigilance.

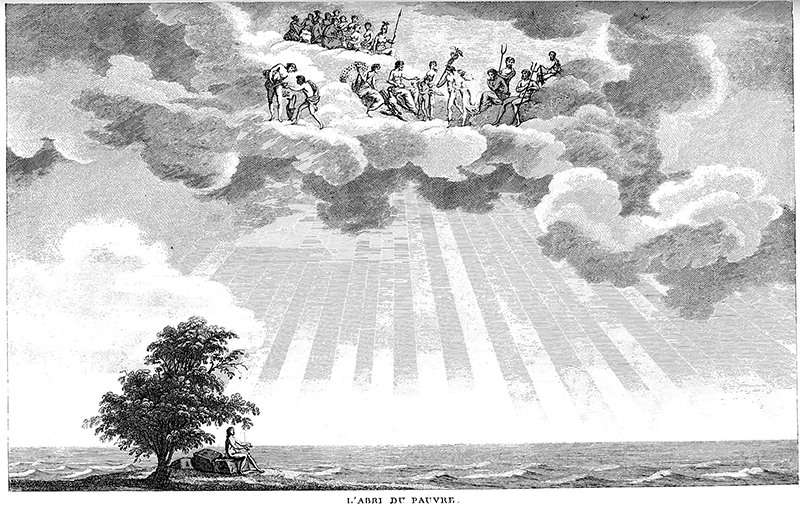

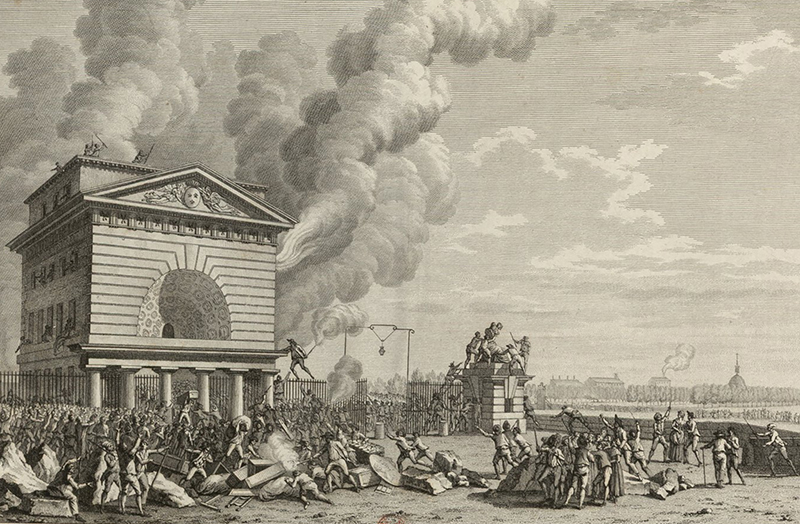

In his self-reflection he wrote: “I will urbanize a population of eight hundred-thousand people to grant them independence” 11. Again, just as he conceived the saltworks, he imposed a new identity, attempting to construct a community through the use of architecture. Yet this time, he may have overestimated the civic influence of his architecture. To the people of Paris, this new identity of the “esprit publique” 13 did not feel like independence. Before the wall was completed, the French Revolution began. Now rejection was no longer on the side of Ledoux, whose attempt was to replace the singular symbolic statements of the Baroque with a syntactical system of architectonic expression for the Age of Reason, but on the side of the people of Paris. They rejected the so-called “language” of Ledoux’s architecture and reframed the societal meaning of these gates: oppression and control by a tyrannical regime. As a counter-reaction, the people burned down Barriére de Passy during the riots of the Revolution [Figure 7].

Fig. 7

Epilogue

Ultimately, Ledoux’s rejection of the classical orders was still obedient to the established system of power, and so he lost the credibility that would have been necessary for the people to accept the identity imposed by his works. From the emerging Republican point of view, he had been part of the Ancien Régime. Moreover, his Architecture Parlante was interpreted more as a display of function than an actual embodiment of a functionality, and despite his rhetoric and good intentions, his gesture of social engineering was perceived to be just as tyrannical as aristocratic oppression. Ledoux rejected the symbolism of classical orders, but his effort to educate people through architecture, to reshape identity from the Baroque to the Enlightenment, was ultimately rejected by the people who, painful as the French Revolution was, chose instead their own path of emancipation.

1 Ledoux, 1981, p.135, Lagemann, D. (trans.) J ́entends le professeur, circonscrit dans le cinq ordres, crier aprés l ́abus: il ouvre son perplexe rudiment, en retourne toutes les feuilles; il ne voit rien dans ces points donnés qui justifie l ́écart. Les regles de la grammariere sont violées, tout est perdu; des colonnes angulaires; a-t-on jamais rien vu d ́aussie ridicule? Le point de doctrine attaqué, défend ses remparts: il a beau afficher ses manifestes insignifiants; il tonne par-tout; les éclats de son tonnerre frappent les murs rétifs du Gymnase, et tombent sans endommager.

2 Ledoux, 1981, pp. 43

3 Ibid: Ledoux, 1981, pp. 224

4 Ledoux, 1981, p. 3

5 Gallet, 1983, pp. 128

6 For example: In his Théâtre de Besançon, he opened up the loges for the Aristocrats in a way that the ordinary people could see what is happening in there. Apparently it was his intention to put a stop to the common habit among the high-borns to enjoy their mistresses during a stage play being carried out. (A.N.)

7 Ibid.: University of Innsbruck/ Peter Volgger: architecturaltheory.eu

8Kaufmann, 1955, pp. 130 and 251

9Ibid: Ledoux, 1981, p. 135

10Ibid: Ledoux, 1981, p. 115

11 Vidler, 1941, p. 106

12Ledoux, 1981, p. 118

13Ibid: Gallet, 1983, p. 114

Dennis Lagemann is a Doctoral Candidate in Architecture. He holds a Diploma of Engineering in Architecture and a Master’s degree of Science in Architecture. He conducted additional studies in Philosophy and Mathematics at the Department of Arts & Design in Wuppertal and at ETH Zurich. He was teaching CAD- and FEM-systems, worked as a teaching assistant in Urban Design and Constructive Design until 2013. On the practical side, he worked for Bernd Kniess Architekten on multiple housing and exhibition projects in Cologne, Dusseldorf and Berlin. In his research activities, Dennis was a member of PEM-Research-Group at the Chair of Structural Design at the University of Wuppertal, where he became a Doctoral Candidate in Computational Design. From 2015 on he is participating in the sci- entific discourse about computation in Architecture and giving talks at conferen- ces, including ACADIA, CAADRIA and ArchTheo. He is now located in Zurich at ETH / ITA / CAAD. His main research interest lies on the question how histo- rical and contemporary notions of space, time and information are being addressed in Architecture.