Ein Sommernachtstraum

Andreas Papadantonakis

In January 1833 the English frigate HSM Madagascar anchored in the bay of Nauplia and amid a scene of extraordinary spectacle, the 17-year-old Otto von Wittelsbach disembarked on Greece. A widely enthusiastic crowd welcomed the young Bavarian aristocrat whom the National Assembly had declared “King of Greece”. During Otto’s early reign and specifically in 1833, […]

In January 1833 the English frigate HSM Madagascar anchored in the bay of Nauplia and amid a scene of extraordinary spectacle, the 17-year-old Otto von Wittelsbach disembarked on Greece. A widely enthusiastic crowd welcomed the young Bavarian aristocrat whom the National Assembly had declared “King of Greece”.

During Otto’s early reign and specifically in 1833, five years after the establishment of the Hellenic State at the Third National Assembly at Troezen (1827), Athens was assigned as the capital city. In these first stages of development after the secession from the Ottoman empire, Greece formed its national identity as a constructed narrative; a self-evident continuation of the ancient past. Athens was the epicentre of this cultural appropriation.

The task of composing a master plan that would transform a village of 20,000 inhabitants into a modern capital was entrusted to two graduates of the Berliner Bauakademie: Gustav Eduard Schaubert and Stamatios Kleanthes. The young architects proposed a new urban nucleus, a neoclassical garden city at the North side of the Acropolis’ hill with a triangular urban form. The masterplan was meant to connect prominent buildings, such as the New Royal Palace and the Academy of Athens with the ancient ruins of Acropolis, while proposing new urban axes. The significance of the strong urban form could simultaneously serve as a guarantor of the new political order and as a flexible spatial framework. Schaubert and Kleanthes’ plan was ratified in July 1833 and until its abrogation one year later, due to the interpolation of various landowners, faced several alterations. The royal palace was then the focal point of most alternative plans.

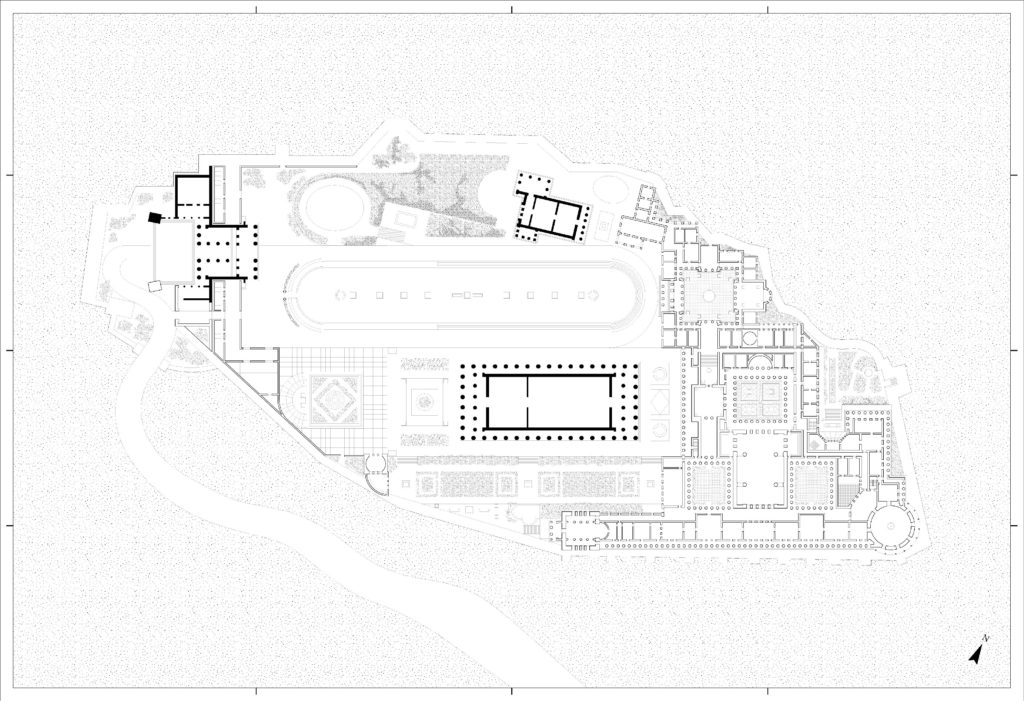

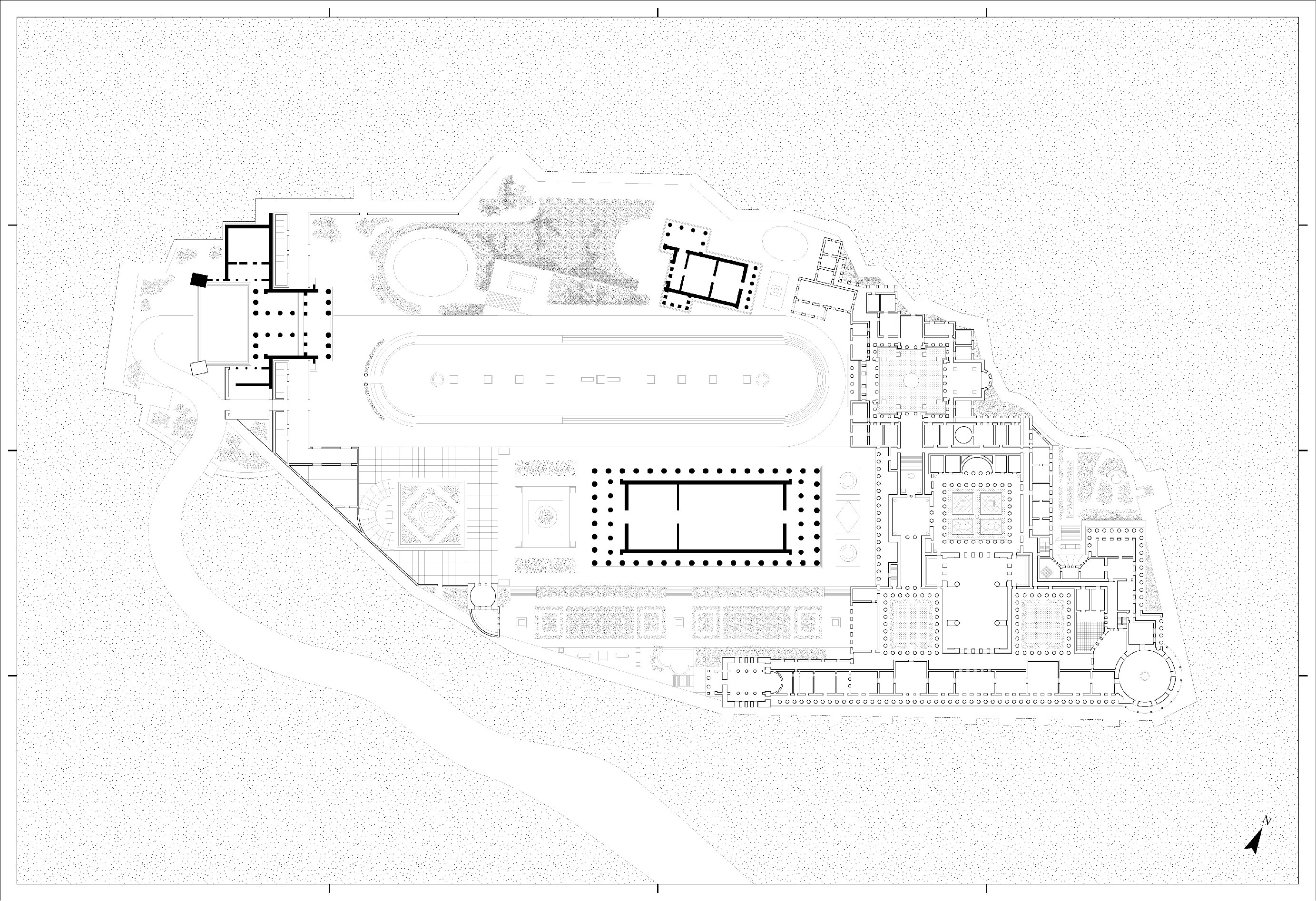

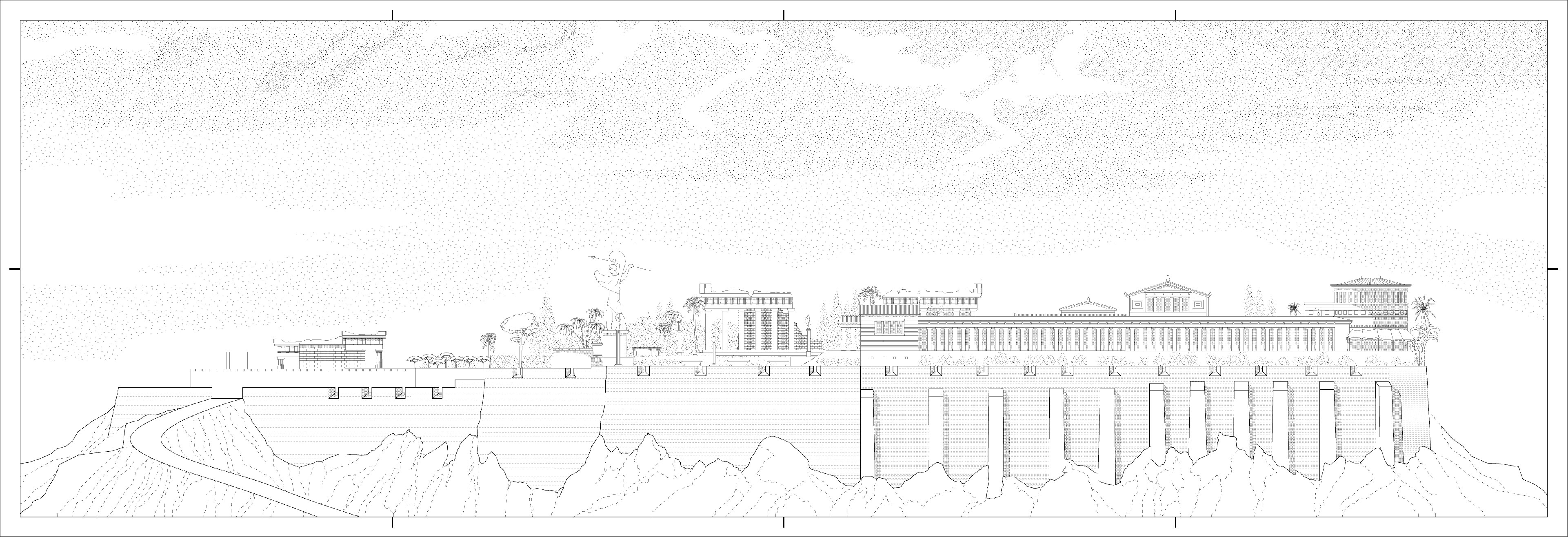

In this struggle, the King of Prussia Friedrich Wihlem III, recommended Karl Friedrich Schinkel, to his friend Maximilian, Crown Prince of Bavaria. Schinkel was very much admired by both Kleanthes and Schaubert, being additionally their professor at the Bauakademie of Berlin. Maximilian, the older brother of Otto von Wittelsbach, solicited Schinkel’s advice regarding the design of the Royal Palace of Athens. The project’s brief addressed the creation of a modern palace for the new monarchy, very well defensible and able to incorporate within it the Parthenon and the rest of the surviving ancient monuments on site. In 1834, Schinkel rose to the task with a design which was expanding over the entire hill. In lieu of a singular building he designed a sequence of one-story high chambers and four courtyards at the Eastern and Southern edge of the Acropolis. The entrance to the complex was, as in the ancient Acropolis, through the Propylaia. Immediately to the east of the paved entrance court was placed a sunken hippodrome between two large landscaped areas with planting, fountains, and seating offering cool and gracious locations from which to view and contemplate the Erechtheion and the Parthenon. The hippodrome was leading from the Propylaia to the entrance hall of the royal chambers. While most of the palace follows Parthenon’s orientation, the northern part of it is aligned to Erechtheion. Both geometries are abruptly cut on the edges of the hill’s fortification. In that way the royal palace completes the periphery of the site and together with the existing Propylaia creates a large courtyard in the middle. The Parthenon would have been the highest and only building existing in that open space. Elements that approached that height, such as the rotunda of the queen’s apartment, were kept at a sufficient distance in order to considerably diminish their apparent size. Luxuriant landscaping softened the contrast between the different parts and helped to unify the whole complex. Schinkel’s proposal balanced a need of monumentality with a smaller scale, making sure that the royal chambers framed the ancient ruins without typologically competing with them.

The architecture of the Royal Palace focuses on a rich sequence of individual interior spaces that reinterpret the classical language reducing it to rich volumes and simplified ornamental themes. Some of the rooms, like the Repräsentationssaal2, reveal as majestic peristyles with direct relation to the exterior and with references to classical themes of decorations. Schinkel produced a complex plan that combines ease of circulation and access with clear functional distinctions. The design had labyrinthian qualities very much alike those of the Bank of England by Sir John Soane and English Neoclassicism in general. Indeed, in 1826 Schinkel made an important tour of Britain, however the assertion with the British architect is not confirmed. Still, the idea to base his architectural composition on a cellular plan allowed his design to fit on Acropolis’ plateau and relate with the existing antiquities. Schinkel who through his career had been repeatedly challenged to accommodate his designs to the difficulties of a specific site3, selected first and foremost to highlight the immensity of the context rather than restore a historical image. The plan would be thus understood as a topology more than a typology. The appropriation of the existing site would gain a self-sufficient completeness through the coexistence of old and new.

The use of a greek-inspired architectural style in the specific context allowed Schinkel to evoke the idea of the past; an act both oblivious and fascinating. Oblivious because it consciously ignores the hundreds of years of cultural fermentation that interpolated the end of the ancient Greek civilization and the birth of the Modern Greek State. Fascinating because it can be viewed from a distance as an aesthetic phenomenon. The ancient past turns into a spectacle and the Parthenon the centre of a composition, remnant of an era that is overcome. In central Europe of the 19th century the Greek ideal was already enlisted in the service of a well-ordered society. Neoclassicism, as a movement, offered the idiom of the high art of antiquity and Prussia’s middle class was expected to conform willingly to the post-Napoleonic, anti-revolutionary order. The Art of Bildung4, a key concept on the formation of the Prussian State promised first and foremost a key role to the bourgeois society. Neoclassicism as a nostalgia for past civilizations and an attempt to re-create order and reason through the adoption of classical form paradoxically turned into a romantic movement. Schinkel – a master of stylistic eclecticism that could simultaneously propose a project in gothic and in classic architecture – by designing a palace next to the most prominent Greek antiquity, transcended the neoclassical style.

If 18th century very famously is the period of the cultural Grand Tour; a desire to know the Italian and ultimately the Greek landscape, in 19th century this tradition was rivalled by a culture of observation tours to the industrialised countries of Europe. The intense quest of national identities in the post-Napoleonic world would lead to an increased interest in the destiny of nations and their historic evolution. A new approach to history would be suggested by architects as Henri Labrouste5, who defended a rupture with the past and questioned the restoration studies of the ancient Greek and Roman antiquities. In Schinkel’s case the departure from neoclassicism, already visible in his design for Friedrichswerdersche Kirche, would also mark a different approach to history. Schinkel himself did numerous travels due to his need to visit cities that were rapidly changing and observe their evolutionary process. The beautiful set of water-coloured plans, sections and elevations6 that he submitted in 1834 to Maximilian, reflected the mutability of form and change. Unlike the dioramas that the young Schinkel produced for the reconstruction of ancient sites, including the Temple of Diana at Ephesus and the interior of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, the delicate coexistence of unrestored ancient ruins with the new royal residence, suggests that the entire setting can be read as a palimpsest of change. Thus, Schinkel was engaged consciously in inventing a fictitious archeology.

When Leo von Klenze, the appointed successor of Kleanthes and Schaubert in the urban planning of Athens, received the plans of Schinkel he referred to them as “a wonderful and lovely midsummer night’s dream of a great architect”. Klenze’s damning with faint praise was based on the assessment that Schinkel’s proposal couldn’t meet the expectations of modern court life. Needless to say, Schinkel’s plan was rejected mainly because of the lack of funds and partly because it endangered the classical ruins. Illusory or not, it is pointless to judge Schnikel’s unbuilt proposal from a pragmatic point of view. It is substantial to approach it as an architectural study that suggests a productive blurring of two asynchronous, yet associated, architectural styles with the scope of framing the identity of a monument and consequently that of a whole state. It is therefore, an act undoubtedly historical.

“The only art that qualifies as historical is that which in some way introduces something additional in the world, from which a new story can be generated”7 wrote Schinkel. For this reason, Karl Friedrich Schinkel perceives history as a laboratory of change and detects its dynamic in the possibility of architecture to redefine identities. In this sense, architecture is not only a built object; architecture is also the very idea of appropriation.

1A midsummer night’s dream; translation

2Entry Hall; translation from German to English

3The most notable examples of the Schinkel’s struggle with the context are two monumental classical buildings in central Berlin, the Altes Museum (1813-1830) and the Schauspielhaus( 1818-1821).

4The term refers to the German tradition of self-cultivation and it was specifically used by the Prussian philosopher and educational administrator Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835). Humboldt developed the term in order to define the way that a person could gain his freedom through a continuous process of self-education and the expansion of cultural sensibilities.

5Labrouste, H 1829 Antiquités de Pestum, Posidonia, Labrouste jeune 1829 [mémoire]. Paris, École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts.

6Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s plans for a palace on the Acropolis were published in the form of elaborate coloured lithographs by Ferdinand Riegel in Potsdam from 1840 to 1843 and 1846 to 1848, under the title Werke der höheren Baukunst zur Ausführung bestimmt (Works of higher architecture, intended for realisation).

7Barry Bergdoll, Erich Lessing Karl Friedrich Schinkel: An Architecture for Prussia, New York : Rizzoli, 1994, 45