An Architecture Without Contempt

Brittany Utting & Daniel Jacobs

French Protectorate architects and urbanists in the early twentieth century—participants in the administrative bureaucracies of North African colonial rule—were confronted with the task of housing populations they saw as living under conditions antithetical to Modernism. To consolidate control over its colonies, France asserted its political and cultural dominance, continuing the inherited myth of the “civilizing […]

French Protectorate architects and urbanists in the early twentieth century—participants in the administrative bureaucracies of North African colonial rule—were confronted with the task of housing populations they saw as living under conditions antithetical to Modernism. To consolidate control over its colonies, France asserted its political and cultural dominance, continuing the inherited myth of the “civilizing mission”1 by overlaying these Protectorates with the urban visions of its Modernist utopias. The Climat de France, an Algerian social housing project built by French architect Fernand Pouillon in 1954, is paradigmatic of this effort. Although conceived by its designer as “an architecture without contempt,” it was commissioned by the French authorities to house and pacify Algiers’ colonial subjects. While the housing project was used as a biopolitical instrument of subjugation and control, architects like Pouillon earnestly sought to transform the agendas of France’s Modernist project to adapt to the aesthetic, ideological, and formal terrains of North Africa. Despite these intentions, the tenants of the Climat have continuously appropriated its spaces through informal occupation and unintended use, transforming it into an important staging ground for protest and revolution. In an era where the lingering stresses of neocolonialism are re-politicizing urban spaces, the history of the Climat is instructional in how Modernism’s legacy can be re-adapted to new ways of life, occupation, and identity.

By the early 1950s in Algiers, local Arab populations had grown in size from 70,000 in 1926 to nearly 300,000 in 1954, rapidly filling up the already overpopulated Casbah and expanding bidonvilles (informal settlements). Due to the increasing hostility of the local populations against the French Protectorate, the Mayor of Algiers, Jacques Chevallier, ordered the planning of several large scale urban housing projects with the intent to relocate, integrate, and disperse Muslim groups. As Protectorate architecture was often used as much for statecraft as urban planning, Chevallier saw this increased modernization as a solution to the situation he saw as “a new and deadly battle, a battle for housing.”2 These colonial projects negotiated a continuous conflict between an offer for improved living conditions in exchange for the inevitable deferral of Algerian self-government, instrumentalizing urbanization “which signified at one and the same time oppression and modernization … yet which also brought hope of other potential ways of living.”3 This ethical and political ambiguity created a fertile new ground for appropriations of these spaces by its colonial subjects, leveraging the monumentality of these architectural prototypes into a later staging ground for revolution.

As the Protectorate witnessed increasing unrest in Algiers’ bidonvilles, Mayor Chevallier and the French army began to build housing projects for Algerian populations as a tactic to control the urban spaces of the city and implement social reform in order to “ensure the survival of the colonial system.”4 Of the architects in Chevallier’s “battle corps,”5 Fernand Pouillon, the newly appointed Chief Architect of Algiers was the vanguard against increased hostility. From 1953 to 1959, Pouillon designed and oversaw the construction of three major projects, each intended to house a different colonial subject: Diar es‐Saada or “Land of Happiness” was exclusively for Europeans, Diar el‐Mahsul or “Land of Plenty” combined both European and Muslim dwelling types in distinct structures, and finally the immense Climat de France, retaining the name of its district, to house an exclusively Muslim population in the lowest-cost and most compact dwelling units.

On November 1, 1954, just prior to the start of construction of the Climat de France, the political situation shifted dramatically when the National Liberation Front of Algeria staged a series of armed attacks and publicly demanded the dismantling of the colonial state, marking the start of the Algerian Revolution. These events forced the French militarization of Pouillon’s projects; as noted by Zeynep Çelik, “the War of Independence transformed the social atmosphere of the settlement, turning the public squares and gardens into proper battlegrounds and army stations.”6 However, it was in fact the inhabitants of these projects that appropriated these colonial tools, transforming what were once spaces of oppression into an arena for political action and independence.

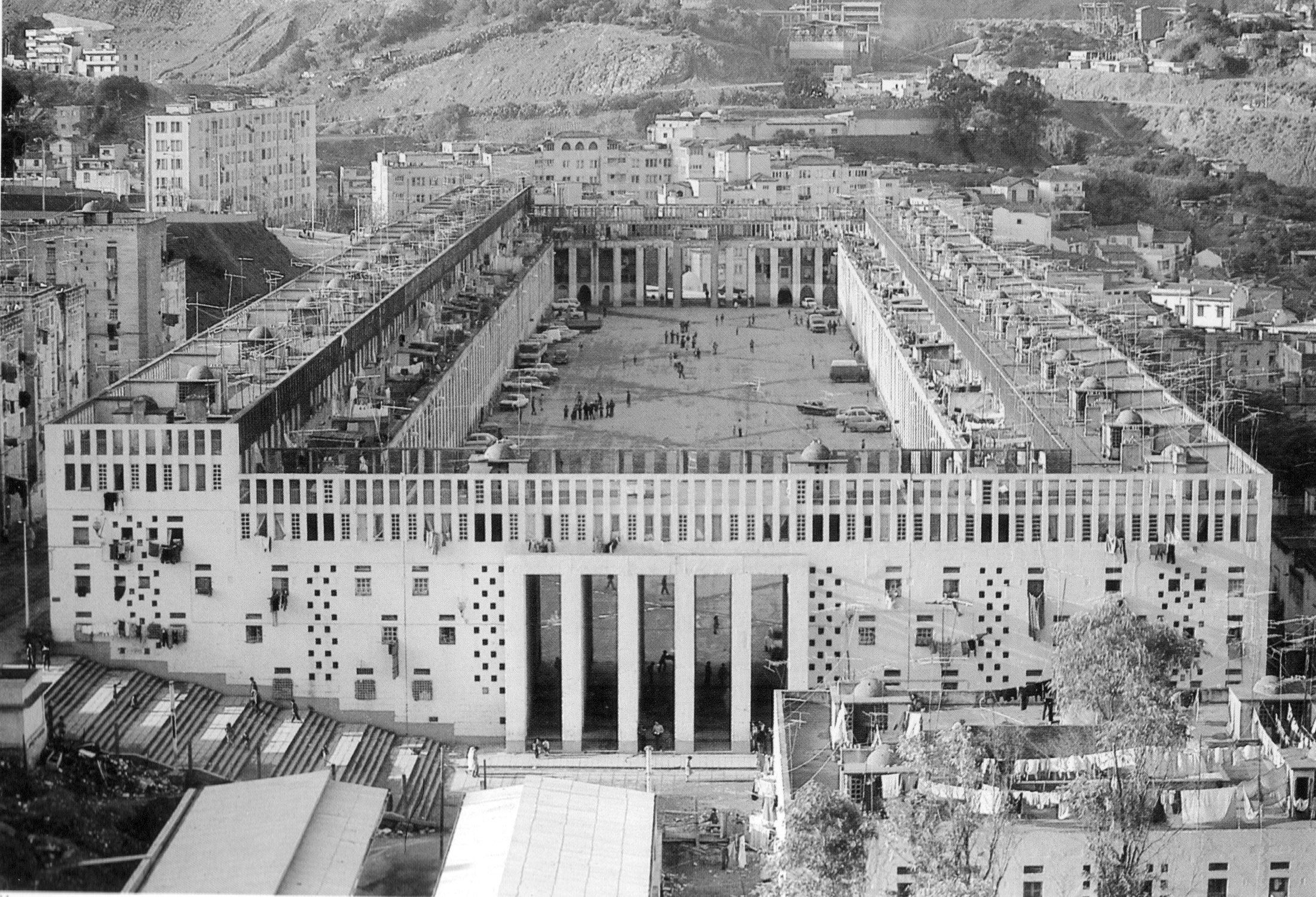

Documented in the famous concluding scenes of the 1966 film, The Battle of Algiers, the Climat de France serves as one of the backdrops for this revolution. The guerilla strategies of France’s army tactically deployed their troops into the streets of the city, infiltrating these new housing complexes to suppress Algerian freedom fighters while also blockading the entry points of the Casbah, preventing the free movement of its residents to and from the fortified quarter. The Climat, constructed in the midst of these uprisings and completed just three years before Algerian independence, became a scenographic stage for the revolution; as the most emblematic of the three projects in both scale and ambition, its iconicity became inextricably linked to the Battle of Algiers. It was among the largest housing projects constructed in North Africa at the time, containing 4,500 dwellings to house over 30,000 inhabitants. The 25 hectare urban plan was conceived as a small, autonomous city with its own hierarchy of streets, squares, schools, services, monuments, and residential blocks, occupying a mostly uninhabited hill to the west of the Casbah. The imbrication of this housing complex and the urban conditions of the impending revolution was paradigmatic of the confrontations between the agendas of modernisation and the emerging identity of the Algerians, notwithstanding Pouillon’s claim that:

“This architecture is without contempt. For the first time perhaps in modern times, we men installed a monument. And those men who were the poorest of the poor Algerians understood it.”7

Nor did the project reflect contempt for its own monumentality. While Pouillon broke down the scale of the site into an aggregation of smaller housing blocks of varying heights—referencing the roofscape of the old Casbah—he cleared away the center of the plan with a monumental courtyard structure, named by its inhabitants as “The Place of 200 Columns,” or 200 Colonnes. This 233 by 38 meter central square was lined with massive three-storey high stone columns and surrounded by ground floor shops and exclusively one-bedroom dwelling units above. These modest units, containing a living room, a bedroom, kitchenette, bathroom, and balcony facing the interior of the monumental courtyard, were united by a public walkway also facing the interior. Pierced by small windows and ventilation holes, the exterior facade of the 200 Colonnes simultaneously evoked a woven tapestry and a fortification. The cloistered interiority of the 200 Colonnes project combined with its overtly fortified exterior, its exclusively Muslim population, and its centrality in the massive Climat de France masterplan, generated a condition ideal for both French Protectorate surveillance and also revolution. Despite claims by the colonial administration that “the settled, well-housed population of ‘Climat de France’ is less fidgety than that of the neighboring casbah,”8 it was from within these same housing projects that the resurgent nationalist protests of 1960 emerged. In his critique of End of Empire cinema, Alan O’Leary writes that “the Algerians may have lived inside the buildings of the Climat de France, but they rejected the designs that its architecture had upon them.”9

While these housing projects were used to symbolically transplant the Western way of life into Algeria, consolidating France’s geopolitical presence and socio-cultural hegemony, these architectural backdrops were in fact co-opted by the same populations they were meant to control. In 1962, just three years after the completion of the Climat de France, the Algerian Revolution successfully overthrew the French colonial regime and France withdrew from Algeria.

Postscript: A Second Appropriation

“They seemed perfectly calm and almost content. Our coming changed nothing.”

– Albert Camus, The Stranger

In the years following the Algerian revolution, tenants of the Climat de France began constructing informal settlements between the housing blocks and on the roof of the 200 Colonnes. Due to the overpopulation and deterioration of Pouillon’s new Casbah, the Climat once again reasserted itself as a prime location for revolution in the 2011 Arab Spring. During the riots, Algerian Police entered the complex to demolish the informal settlements, resulting in clashes that left seventy people wounded. Even today, these housing complexes are still spaces of protest and unrest, inheriting the legacies of neocolonial oppression and daily hardship. While on the one hand it is the inadequacies of these projects as both urban solutions and socio-political programs that produce the struggles of daily life—insufficient housing, urban infrastructures, and scarcity of resources—it is this same architecture that is used by its occupants as a symbolic frame for political resistance. Coupling a nostalgia for a radical past with an ongoing revolutionary necessity, the monumentality of the architecture provides an aesthetic ethos for these recurrent projects of dissent and defiance. This recursive history of the Climat and revolution exposes how French colonial intentions in Algeria and Pouillon’s specific vision were opportunistically appropriated to enact new forms of life and stage new models of protest within the contemporary city.

“It’s hard to start a revolution. Even harder to continue it. And hardest of all to win it. But, it’s only afterwards, when we have won, that the true difficulties begin.”

-Ben M’Hidi, The Battle of Algiers