Assimilation of Rome

Dennis Lagemann

Introduction On August 24th, anno domini 410, northern swashbucklers have decapitated the mother of the world and left the Italian cities as parts of a corpse. Over the following centuries the grandeur of the ancients became tales to be told on the hearth fire and the ruins of the old world, aqueducts and forums, ramrod-straight […]

Introduction

On August 24th, anno domini 410, northern swashbucklers have decapitated the mother of the world and left the Italian cities as parts of a corpse. Over the following centuries the grandeur of the ancients became tales to be told on the hearth fire and the ruins of the old world, aqueducts and forums, ramrod-straight roads and statues were no more than silent witness of a gracious past, furnishing the landscape. Powerless, except for keeping their secrets. Conquered by barbarians, the identity of the proud Roman citizen, ruler of the world, was cut off.

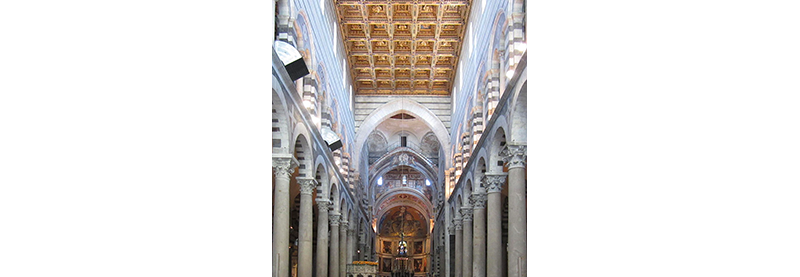

These admittingly pathetic lines are an attempt to give an impression of the melancholy that may have captured the Italian cities at the beginning of the middle ages. In the aftermath of this, many generations since the fall of Rome, Venice, Genoa, Pisa and many more Italian cities either became a republic of their own or independent capsules within the Byzantine or Frankian empires. But, regardless of their new independent status, the built architecture of this time reveals that the city-states presented a lack of a clearly defined own identity under the dominion of Byzantium and the Holy Roman Empire. At the same time, northern Italy became a hub for the trade between Asia and Europe, giving rise to successful and assertive merchant families, who could afford to employ stone-masons and master-builders from abroad. But this also meant that these paid workers brought their own ways of how to build. Which may be the reason, why edifices of those regions and time display a conglomerate of Gothic and Byzantine influences alongside fragments of Roman heritage, like the sacral Cathedral of Pisa (Fig. 1) or the profane Doge`s Palace of Venice.

Fig.1 Cathedral of Pisa

For the citizens of italy, this may have resulted in a strange situation. Wealth and self-confidence had raised the demand for independence, while the borrowed identity of recently built edifices somehow conveyed a kind of dominance. At the same time, the remains of a greater past still were present in the surrounding environment and so the idea may have appeared to rather step in line with the ancient heritage.

In Search for Harmony (Raising the Dead)

On the verge of Renaissance, Ciriaco de Pizzicoli, who is said to have been one of the first archeologists, started to investigate on the remains of the great ancients. Although Ciriaco and his mecenas Cardinal Bessarion were more drawn towards Greek tradition, they affirmed the image of the Roman citizens as “good-natured people” and the perpetuation of Hellenism within the Roman Empire (Lamers, 2016, p.109)1. Ciriaco referred to built artefacts rather than written documents because he deemed them to be more reliable than parchment (Mangani, 2017)2. But other than the interwoven fabric of mysticism and passed-on experience about material properties of the elaborate gothic canon, suitable to praise the Lord but not to serve Man, these artefacts were still silent. So all Ciriaco could do in order to distinguish the regional Italian city-states from imported canons of form was to draft and sketch, to copy motifs and to measure geometric relations. In the expelling of medieval dogmatism from this seemingly superficial investigation, a deeper sense was presumed to be found in the ancient proportionality.

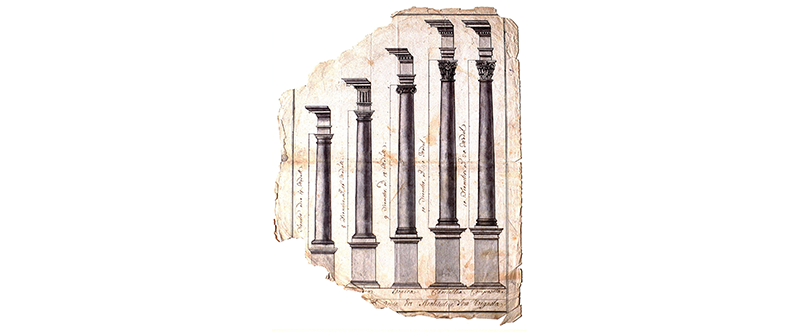

Alberti took up Ciriaco`s thread and developed his instrumentis mathematicis for further investigation (Fig. 2). He distinguished between the beauty (pulcheritudo) that comes from within, touching the soul of the observer from decoration (ornamentis), which at best may cover a flaw. Other than the contemporary understanding of beauty, this reduction on purely geometrical relationality was not superficial at all. This beauty was seen as the result of a harmony living within proportions. All these forms had to have a meaning but the sense they were supposed to make had to be re-established. And so Alberti posed the question:

Fig.2 Della statua Milano 1804.

And now again, what can be the Reason, that just at this Time all Italy should be fired with a Kind of Emulation to put on quite a new Face?3

He leaves the answer to this question open, but he answers it in exemplifying the aesthetics of antiquity as defined in fixed ratios and measurable proportionality.

So, in order to not simply raise the dead, but to make them talk how to revitalize this touch of the soul, Alberti created a first step towards the assimilation of Classical identity. In this respect, his lineamenta were nothing less than the invention of a level of information on which all the individual fragments of ancient artifacts could become identical. With only two elements, the line and the circular arc, he established a space of comparability on which the secret of beauty could be deciphered.

Constituting Identity

Today, it seems to be a commonplace that with the appearance of the lineamenta, the plan was invented and the modern Architect emerged. William of Sens, Gerhard von Rile and Peter Parler, three medieval Architects, famous characters of their time, would probably disagree. These were all distinguished personalities. Gerhard von Rile left us “Riss F” (Fig. 3), the oldest still existing elevation of the Cologne Cathedral, Peter Parler handled many construction sites at the same time, among them the St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, the Charles Bridge, and the Church of St. Barbara in Kutna Hora.

Fig. 3 Kölner Dom Riss

But if it is not the person of the Architect or the ability to draw plans, what has changed? The three mentioned medieval builders, although they would probably suit the modern image of “the Architect” by far better than these weird eccentrics of Renaissance, were born as sons of a mason, raised in a mason-family, educated as an apprentice to a master of the brotherhood of masons, and consequently, becoming fellow guild members. Their identity was a gift to the cradle and a cage for life.

Quite unlike Alberti, who was an illegitimate merchant son from Genoa. He had acquired his knowledge in schools and not as a family member within a brotherhood. He had to develop his individuality before he could start to constitute identity. So, a part of his writings is basically about defining himself as an Architect. He reframed the image of the Architect under a new premise, stating that an Architect should have clarified and solved all questions concerning a particular building in advance, including those of detailed geometrical solutions. Furthermore, he should keep an overview of how to finish the construction within a manageable time frame.

Fig. 4 Vignola’s Columns

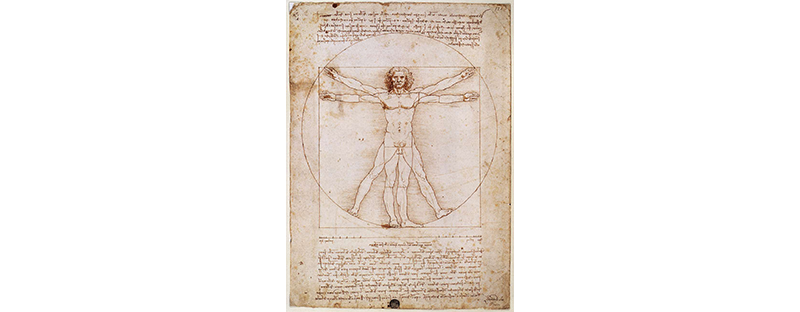

Yet, it appears to be a bit bold to state that with the lineamenta the building would have become a mere copy of the plan. This idea is probably based on a cite of Alberti, where he says that it is possible to find the same lines on a large number of buildings. But Renaissance did not actually produce identical buildings. It seems more likely to assume that on the informational level of the lineamenta the identity between parts of buildings, is being revealed. Alberti had a name for this. He called these identical parts membra and explicitly related those to the limbs of living beings. And this is exactly why thinking about the seemingly superficial beauty of things becomes so important to Alberti and his successors. They expected to find the secrets of the harmony of life in the geometrical relations of the ancient artefacts. Alberti also found a name for this and he called it concinnitas, the harmony that resides in between proportions. The lineamenta, identical to each other on an elementary level, were identical to the morphisms, found in artefacts and at the same time served as blueprints to create new artefacts and perpetuate the dignity of the great ancients. The bearers of beauty, the keepers of the secret of concinnitas are identical parts, while every building remains to be an individual. Technically, buildings of Renaissance had been facsimile, similar enough to keep a certain identity while each one is as individual as any corpus. Like Alberti was relating the parts of buildings to limbs of beings, the sketch of the Vitruvian Man fusing the circle and the square displays identity only on the level of geometry (Fig. 5). Giving a hypothesis, one could say that Renaissance pushed identity from the medieval cage for life to the level of information by assimilation of the morphisms of ancient Rome.

Fig. 5 Vitruvian Man

To Serve and to Comfort

Just as Ciriaco was interested in finding clues to human dignity by examining ancient artefacts, Alberti was interested in extracting a new sense from the meaning of the alphabet of ancient forms and in order to comfort human needs. So it seems hardly surprising that Alberti opposed the Vitruvian virtues “firmitas, utilitas, venustas” with his own categorization in order to get to the bottom of identity as comfort. His own categories maintain the trisection of the spectrum of building requirements, but he replaces durability by necessity, utility by commodity, and attraction by pleasure (voluptas).

In this span of utilizing the same membra on the informational level for individual buildings, the assimilation of identity enters into a kind of double relation. On the one hand ancient forms have been assimilated into Renaissance Architecture to establish an identity, which lies in between the Italian city states and the heritage of the Roman Empire in distinction to medieval mysticism. On the other hand, the regional and local building techniques and traditions were assimilated to establish an identity based on Italian ars vivendi under the purpose of giving comfort.