Perpetual Perspectives.

Aslı Çiçek

The oldest surviving, full translation of Euclid’s Elements has been made by Adelard of Bath in XII century, from an Arabic version into Latin. The title page of the book is an illustration, which shows a woman, holding a compass over a table laid with other tools and few students watching her. All figures are […]

The oldest surviving, full translation of Euclid’s Elements has been made by Adelard of Bath in XII century, from an Arabic version into Latin. The title page of the book is an illustration, which shows a woman, holding a compass over a table laid with other tools and few students watching her. All figures are placed frontally while the table top is seen from above. The rules of perspective are not respected but there is still a spatial depth to the depicted scene. The decisions of how to show what are precise, framed in the bowl of the letter P drawn in red. This type of drawing wasn’t unusual in the Middle Ages; the rather unusual element in the composition is the personification of Geometry as a woman 1. The illustration itself is an example of ‘miniature paintings’. Their main characteristics are not being concerned with light, proportion within the context or representing the reality one to one. The description of miniature comes from minium in Latin for the lead, which was used to produce the red pigment to delineate the content of the illustration. The term also refers to miniatura in Italian, which, given the small sizes of these drawings in handwritten illuminated manuscripts, has become a fitting etymology as well.

Woman teaching geometry

Having grown up in Istanbul and long before I acquired my architectural formation at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich I had seen countless mosaics in similar fashion, narrating -mostly- biblical stories in byzantine churches and colourful miniature drawings depicting scenes of the Ottoman court life or the cities concurred by sultans. All these drawings were fascinating to the eyes of a child in their narrative qualities rather than representing reality accurately. They left some space for imagination since they have been made through choices on how to represent each object in a scene in the best way- even if it would create an impossible composition in terms of reality.

Mosaic Chora XIII century.

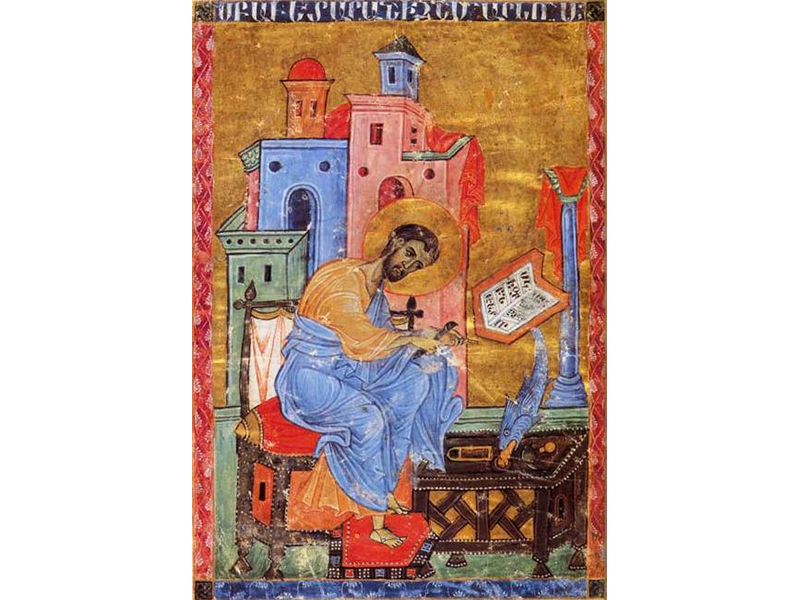

In youthful attempts of liberating myself from my Turkish roots and becoming ‘as European as possible’ I took a big detour via what I found necessary to appropriate, among others also the ‘European’ techniques of drawing until, several years later, I came back to recognise the qualities of this object related thinking of miniature drawings. I also had to discover that the miniature drawing commonly associated with islamic cultures, had actually a much longer history, of which a considerable part belongs to Christian imagery in gospels. In medieval times the masters of these illustrations were Armenians who have been influenced by the Byzantine art and later reigned by the Ottoman Empire.

Armenian Gospel 1260

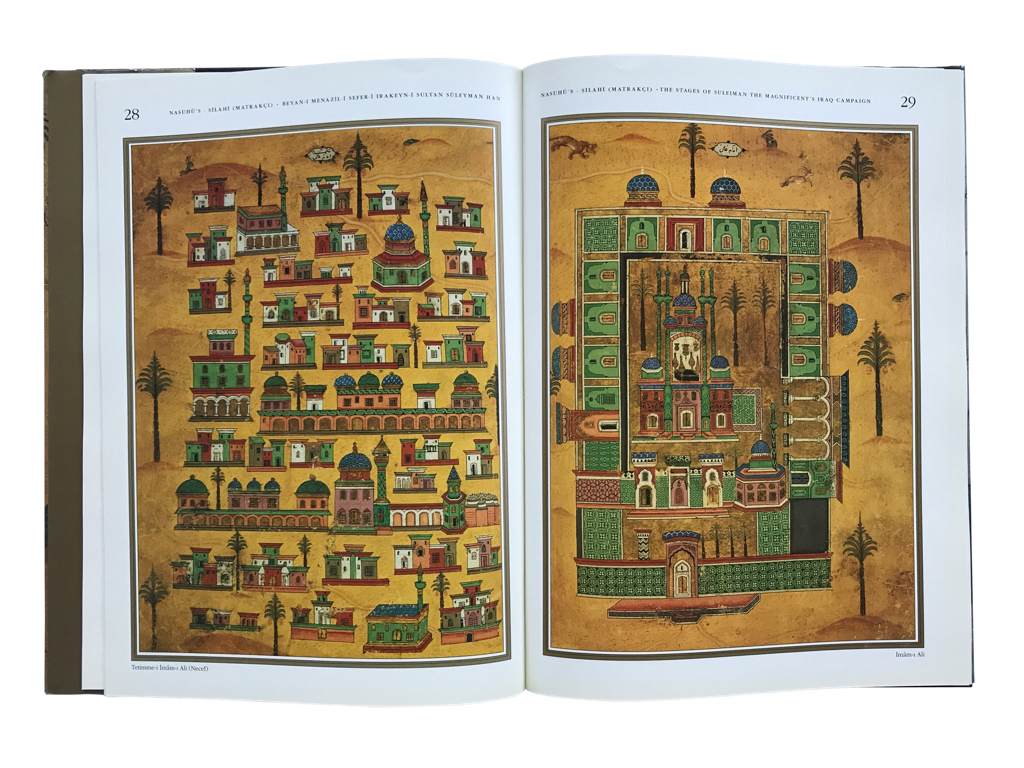

Mixed with the elaborate Persian craftsmanship of the miniature paintings this form of art reached a refinement in the XV and XVI centuries, which is to be seen in several chronicles of campaigns of Sultans or the daily life in Topkapı Palace. This period coincides with two important moments of European history: the invention of printing press in 1450 by Gutenberg and the establishment of the geometric rules for accurate representations of reality during Renaissance. Both meant the disappearance of miniature painting from the European tradition, first causing the replacement of handwritten manuscripts with printed books and the latter by the improvements in perspective drawings both technically and artistically achieved by masters such as Da Vinci, Della Francesca, Dürer and Van Eyck. The differences in attitude between the search for perfection in perspective drawing and the subjectivity of miniature paintings become unmissable if the etching of the Perspective Machine of Dürer is viewed next to any illustration from Chronicle of Stages of Iraq and Persia Campaign by Matrakçı Nasuh 2 .

Topkapi Hoflebe, Nasuh Süleymanname XVI Century

Both worked around same time slot but are entirely different in their aims. Dürer looks for methods to measure and project a scene onto canvas. He even creates a tool for that and meticulously observes the scene to ‘re-construct’ it. His contemporary, the miniaturist, takes every piece of building on its own right, turns them around the way they should be seen. The space left in between them loses its direction and overall scenery is made in the way the miniaturist wants us to see it. The movement between the buildings or interiors doesn’t follow one direction, some of the pieces are seen from above, others in elevation or in perspective. Colours replace the game of light, but the seeming flatness of the illustration bears more depth than seen by the first glance.

Dürer Perspective Machine 1526

Evidently the topics differ between islamic and christian narratives even if islamic miniature drawing has taken over some stylistic notions from christian traditions. Nonetheless, a crucial change of attitude is also perceivable. While the Renaissance increasingly emphasised the authorship of the artist, the islamic miniature paintings were mostly attributed and unsigned. Also human figures are absent in the city depictions of illustrators such as Nasuh.

Nasuh City of Necef Big ca. 1530

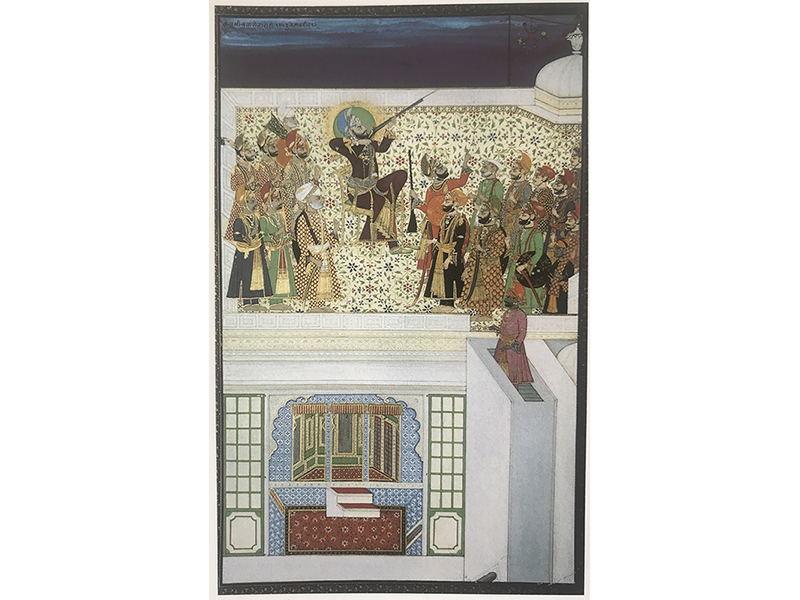

Both these withdrawals are related to the sufi tradition which doesn’t put value on the human life since it describes it as temporary, hence not worth to be represented. This marks perhaps the value of the controversial issue about cultural assimilation: the Ottoman miniature painting grew further in its own way, despite stylistic miscellany fed by other cultures. When two centuries later the Ottoman Empire entered a messy Westernisation process mainly by mocking and importing European ways of life the miniature paintings became an eclectic mixture between correct perspectives and stylistic habits. More elaborate, elegant pieces were produced in the far away Indian court, showing beautiful architectures with scenes generous on narratives and human figures. The quality of miniature being a subjective interpretation of a scene and letting objects relate to themselves rather than one absolute composition survived in those paintings until XIX century.

Mughrab Hofleben XIX century

Despite the freedom these miniature drawings offer in the representation of reality my interest lays more in the way of thinking that comes along with it. During architectural studies various skills are taught, which help to communicate the architectural statements, suggestions. Those skills remain only mediums to provide solutions to problems if they are not mixed with personal fascinations; but architecture made without fascinations remains flat and generic on whichever scale it is produced. As solution-oriented approach always hits its limits to deal with the complexities of the world the aspect of fascination feeds the drive to create instead of to solve. I operate in a niche of architecture where the coherent atmosphere surrounding objects, artefacts is more important than a solution-based approach. My projects are usually categorised as scenography but I cherish more the definition of exhibition architecture. For a long time scenography has been a term only in theatre where a scene is watched from a static position of the spectator. In his Ten Books of Architecture Vitruvius describes skēnographia as the representation of buildings in perspective, their façade and sides on one drawing. The term also includes the design and painting of a scenery supporting a narrative; the setting consisting of representational or abstract elements, the creation of dramatic effects by steering artificial light and design of costumes. But the spectator remains on his chair, the actors move on the stage.

Yet precisely this static position of the spectator watching a scene is the main reason why I refer to my practice as making ‘exhibition architecture’. In an exhibition the spectator moves and the main figures of the narrative stay on their assigned positions. Architecture, being different than painting and in its nature closer to the sculpture, requires the movement of the human to be fully experienced. While designing architectural spaces this idea of movement starts usually with circulation diagrams, sketchily spreading arrows over floor plans. It is not different while designing exhibition spaces: there is an entrance, an exit and a narrative path to be followed in between. Yet like walking between the buildings in a city also in exhibitions every piece can be approached from various directions and experienced differently. This very banal recognition of movement through the space and its ever-changing perception defines my approach to the (museum) space: rather than making rooms I work with elements which don’t only give a background to the exhibits but also refer to themselves. The narrative of the exhibition has to happen in between those and remains an open, ‘undecided plane’. This approach grows almost naturally with my personal fascination for the miniature paintings and perhaps it indicates a certain assimilation of methods lying far from my discipline.

La Perspective_Jean François Nicéron XVII century.

Nevertheless, in cultural production (to which architecture certainly belongs) nothing comes without the confrontation and processing of the already existing. Obviously much of the education concerning cultural production involves acquired knowledge both theoretical and practical. Thereby knowledge can be described as a sum of what is known, but what is known is not only what is learned. There are many things we know before we learn others, things we experience and forget, fascinations which are related to memories and memories, which create fascinations. The beauty of knowledge lays in its perpetual character and the formation, change, interpretation or adaptation of ‘the known’. All our senses contribute to the notion of knowledge, associations mingle with our perception; as a result identity emerges from revisiting our personal and global history.