The architecture of the territory ?

Milica Topalovic

CHAPTER IV: THE EVOLUTION OF URBAN ARTIFACTS The Urban Scale Fifty years after The Architecture of the City, should architects consider the Architecture of the Territory? In the mid-1960s, Rossi’s book revolutionised ways in which architects engaged with urbanisation. The megalopolis, the urban region and the levelling of differences between the city and the […]

CHAPTER IV: THE EVOLUTION OF URBAN ARTIFACTS

The Urban Scale

Fifty years after The Architecture of the City, should architects consider the Architecture of the Territory?

In the mid-1960s, Rossi’s book revolutionised ways in which architects engaged with urbanisation. The megalopolis, the urban region and the levelling of differences between the city and the countryside, were the characteristic urban phenomena of the period. Fifty years on, the scales of the urban have continued to magnify, and architectural tools for dealing with them have continued to erode. Rossi’s text remains relevant; it sounds even truer today. Should then the scope of the discipline of architecture be broadened once again, beyond the limits of the city, to include urban territories? Do the scales of urbanisation today demand a larger view?

(…)

Of course, territory is nothing new for architects. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there is a history of architects’ engagement with territory and urbanisation: Major modern architects have taken as a base of their projects extra-urban developments arising from industrialisation and rural exodus.

This history has not yet been written, but many fragments exist. André Corboz, among others, in his text La Suisse comme hyperville (Switzerland as Hypercity), proposed that theories of urban design approached the problematic of urbanisation in four distinct periods.

The first period, according to Corboz, aims to project “the city outside the existing city:” In 1859, Cerdà projected the urban fabric of Barcelona from the walls of the historical city outward to incorporate the neighbouring villages. His seminal work was the 1867 Theory of Urbanisation – in fact, the term urbanisation is credited to Cerdà.

Related projects dealing with urbanisation in this period are Soria y Mata’s Linear City from 1882, which organises urban fabric along public transport lines, and Howard’s Garden City from 1902, which aimed to create a network of small towns that would combine the advantages of both rural and urban living – a concept that has been realised over and over until today.

The second period in this development is marked by the Athens Charter drafted in 1933. This is, confirms Corboz, an urban design theory “against the city” whose ideal is to replace the “unplanned” development of settlements, sometimes including historical ones, with socially, technically, and hygienically “controlled” urban structures. In the same year, Walter Christaller proposed another highly influential theory, the Theory of Central Places. A Swiss example from this period is Armin Meili’s Landesplannung (“regional planning”) from 1941.

What these theories had in common was a hierarchical vision of socio-spatial organisation, anchored at the scale of national territory and corresponding to the Fordist organisation of economy. However, while the theories argued for the complete control of urbanisation processes under the patronage of state, in practice, a major part of that responsibility was handed down to individuals – the atomised texture of private dwelling became significant part of the fabric of the modern metropolis.

The third period of a backlash against excessive simplifications of the visions of the Modern, especially the reduction of the city to four basic functions, can be termed, Corboz suggests, “urban design within the city.” It is based on The Architecture of the City as the key text, calling for the return to the idea of a city as a historical continuity. But architects in this period continue to see the territory as a theme of architecture, embracing the facts of urbanisation beyond the canon. Proponents include Ungers, Koolhaas, Venturi and Scott Brown, Rowe, and so on.

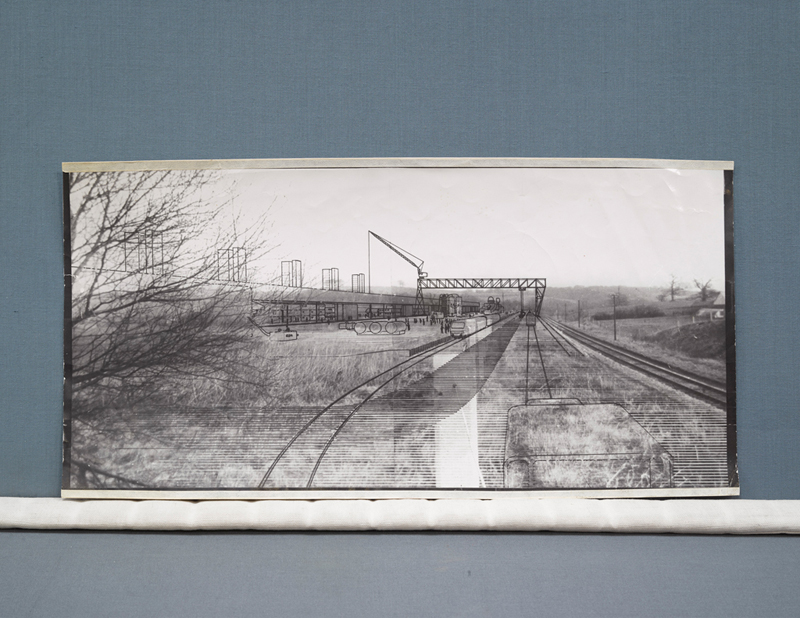

An exceptional project of the period dealing with territory is Cedric Price’s Potteries Thinkbelt from 1964-66, concerned with reclaiming the derelict infrastructure of coal mining in the region of Manchester, for the creation of a university – a visionary proposal for a new “knowledge economy” alternative to the declining post-industrial landscapes of Europe. The project was not realised, and the former mining area was returned to nature; today the site is a beautiful piece of wilderness. (Figure 1)

The fourth period in this trajectory is ongoing, and its paradigm is still being negotiated. The defining condition is the merging of urban and territorial scale – in Corboz’s words, “co-existence of city and territory.” Many concepts have been coined to describe this condition, including cittá diffusa, zwischenstadt, and decentralised concentration. Notable in this context is Andrea Branzi’s Agronica—both a project and description of what he calls weak urbanization, horizontally spread across territory. Crucially for the territorial approach to urbanism, in this project Branzi expands the regular urban program to include agriculture and energy production.

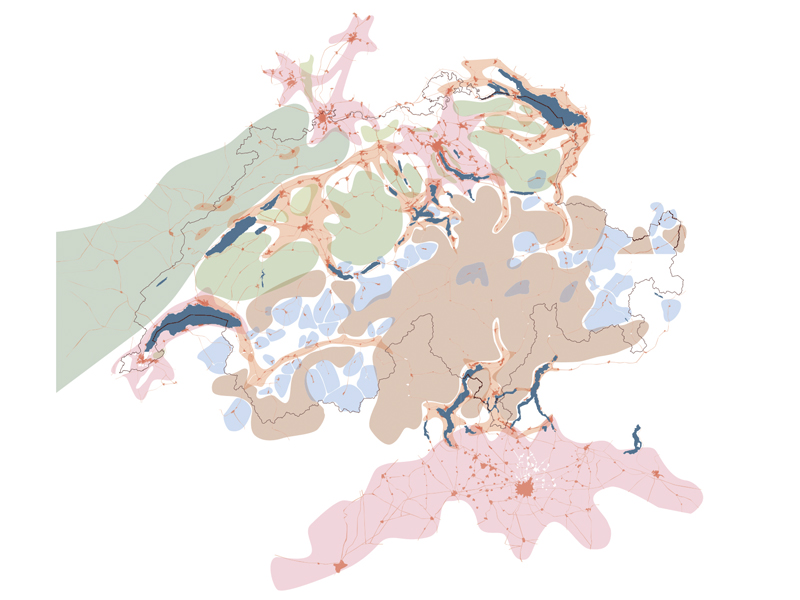

In a groundbreaking analysis of contemporary urbanisation entitled Switzerland: An Urban Portrait, in 2005 ETH Studio Basel put forward a thesis of Switzerland as a completely urbanised country. They show urbanisation putting pressure on the cellular structure of the Swiss commune and forcing the fabric of territory into new differences. The thesis also showed these differences as being no longer local, but increasingly integrated into the cross-border European context. (Figure 2)

Along this trajectory of planning and designing urban territories and urbanisation processes, in shifting from the period of Fordist economy – which emphasised the national scale – to the period of neoliberal globalisation, the national territory has been abandoned as a relevant scale of planning, with some variations from country to country.

The national planning concept was replaced by a more flexible or provisional idea of strategic planning and by a focus on select strategic territories. Broadly speaking, urban areas or agglomerations today receive different amounts of attention in terms of investment and disinvestment. There is no specific relevant or fixed territorial scale; the scale or the frame is always contextual.

Linked to the same transformations is the changing position of architects among other relevant protagonists in urbanism and territorial or spatial planning. The new constellation foregrounds the role of engineers and engineering approaches as relevant to territorial planning, rather than the role of architects and urbanists. At the same time, as a consequence of these transformations, there is a shifting of the typical task of the architect into smaller spatial scales, from territory and city back to the building.

Looking at the examples I have mentioned, it is apparent that in different historical and political circumstances, the challenge of territorial urbanisation has been a constant: Territory was not a minor problem that has only recently gotten out of hand. The assumption that the late-20th-century city is ungovernable and unplannable, driven by laissez-faire politics, has given many architects an alibi for retreating into their strict professional mandate; but this is not any truer today than it was before. In fact, architects have continuously reinvented urban territories and the playing field of their practice. It follows that, as in all previous periods, architectural engagement with territory is still relevant and necessary.

What can architects today bring to territory and territorial scale? What should be our programme?

Research beyond the boundaries of our discipline. I believe that in our discipline we do not have enough experience to tackle the problematic of urbanisation alone. New interdisciplinary constellations should be built up – I believe that the link between architecture and urban geography is crucial.

Furthermore, an important means of engagement with landscape and territory comes through visual arts, and through ethnographic practices – in keeping with Lucius Burckhardt’s practice of walking, for example.

In this new constellation there is an urgency of broadening the understanding of territory from the purely technical or administrative domain. Territory is a social and cultural fabric that architects are familiar with.

Design. Among other disciplines dealing with territory, architects’ strength is design. Architects and urbanists have the advantage of synthetic thinking about territory beyond narrow specialisation. Such synthesis is possible only through a qualitative and contextual approach.

Architecture and urbanism beyond the limits of the city. The idea is not new – throughout the 20th century the urban and the city have been elusive, unstable categories. For example, the recent concept of planetary urbanisation theorised by Neil Brenner and Christian Schmid, was helpful in reframing the urban problematic. Once again, architecture and urbanism should extend their geographical field beyond the limits of the city to the research and design of urbanising territories.

Note: This is an edited excerpt of Milica Topalovic, “Architecture of Territory—Beyond the Limits of the City: Research and Design of Urbanizing Territories,” lecture, presented at the ETH Zurich on November 30, 2015. For the full transcript of the lecture, see http://topalovic.arch.ethz.ch/materials/architecture-of-territory/