The ordinary in the problem of housing

Laura Bonell and Daniel López-Dòriga

CHAPTER IV: THE EVOLUTION OF URBAN ARTIFACTS The Housing Problem What follows is a compilation of 24 floorplans of existing dwellings in apartment buildings in the city of Barcelona. All of them with the north up, all at the same scale. Neither the name of the architect nor their precise location within the […]

CHAPTER IV: THE EVOLUTION OF URBAN ARTIFACTS

The Housing Problem

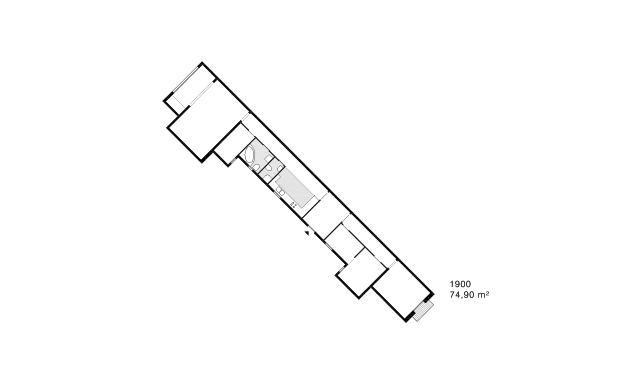

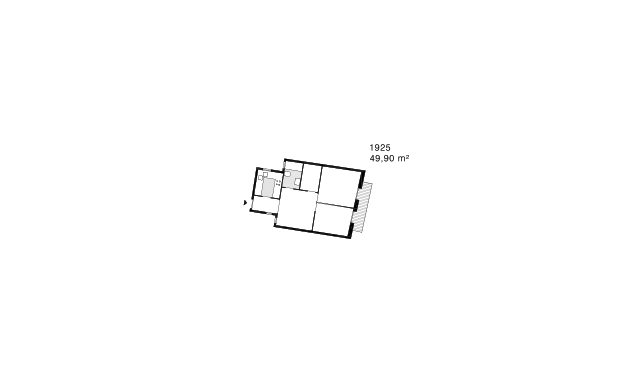

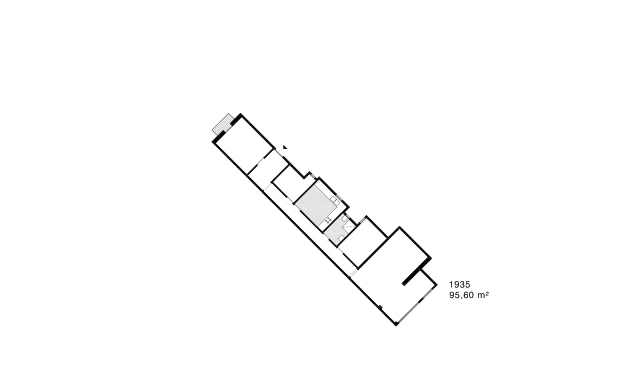

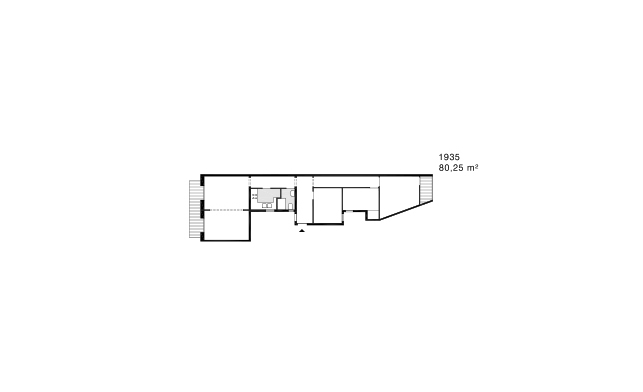

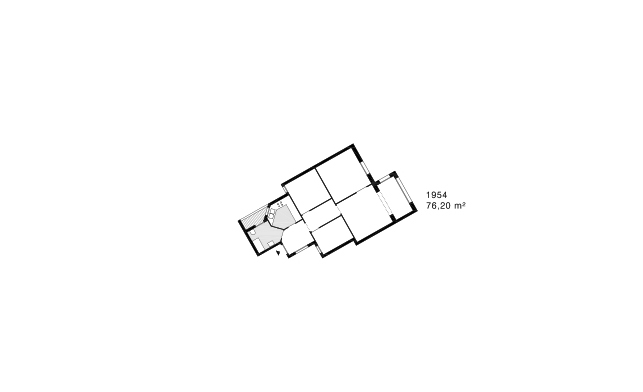

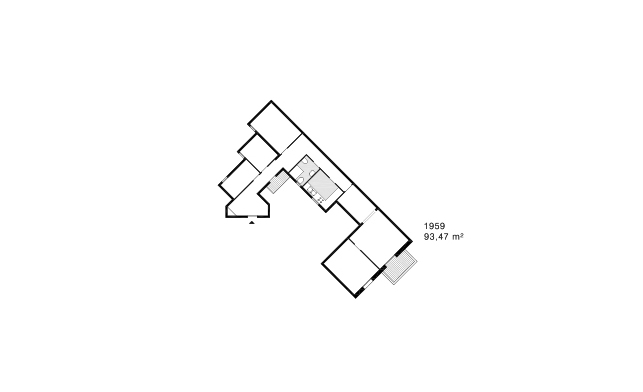

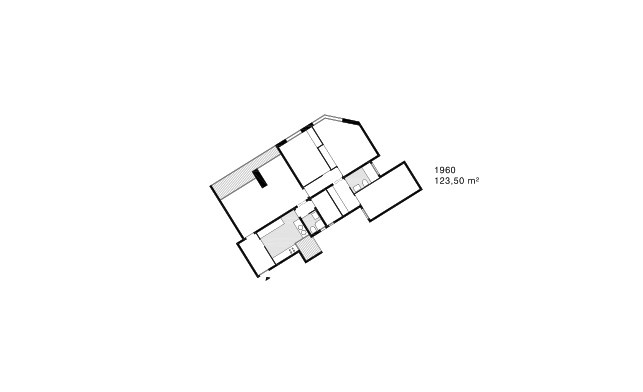

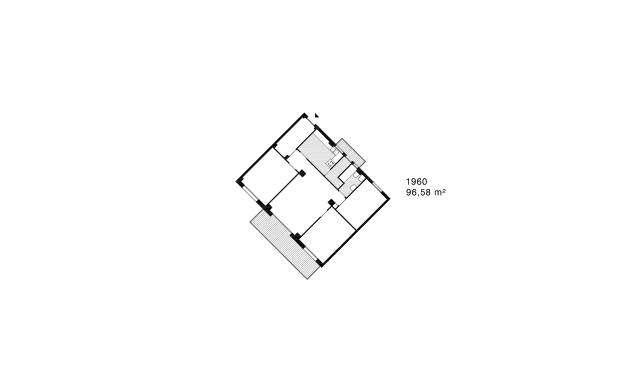

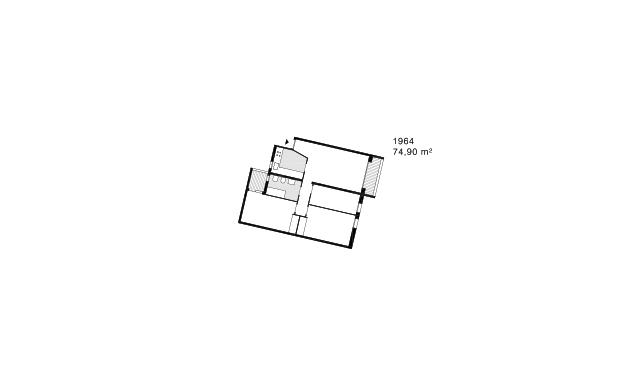

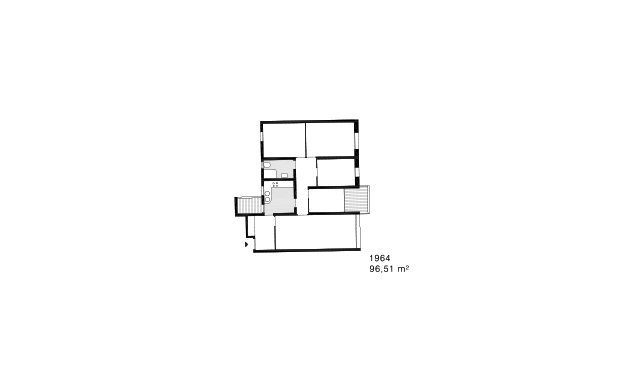

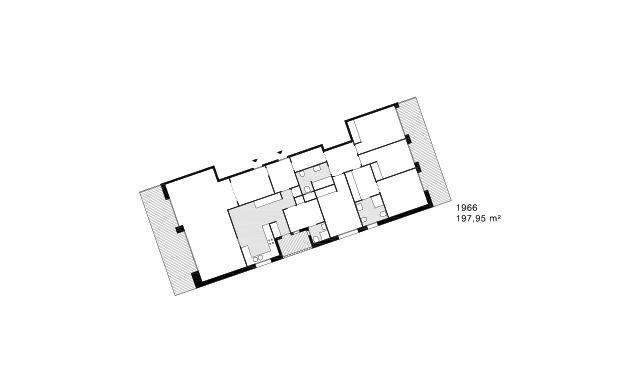

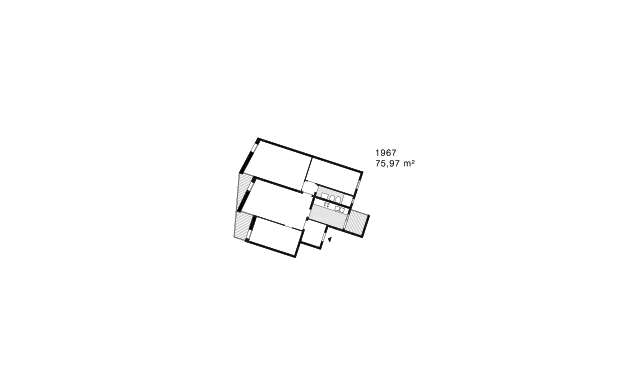

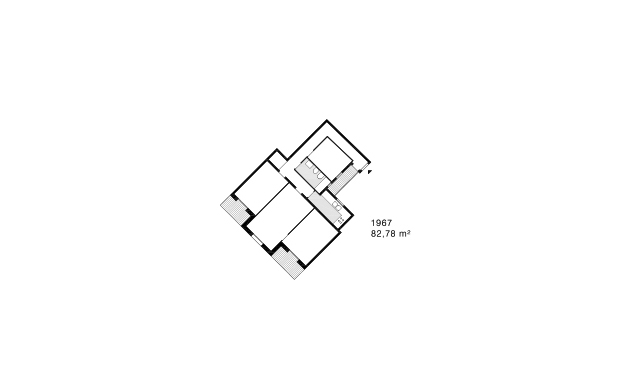

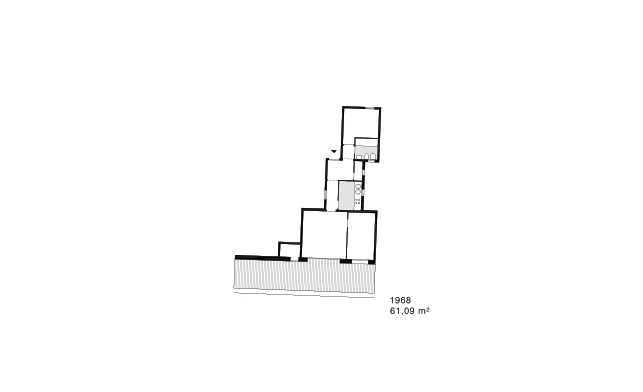

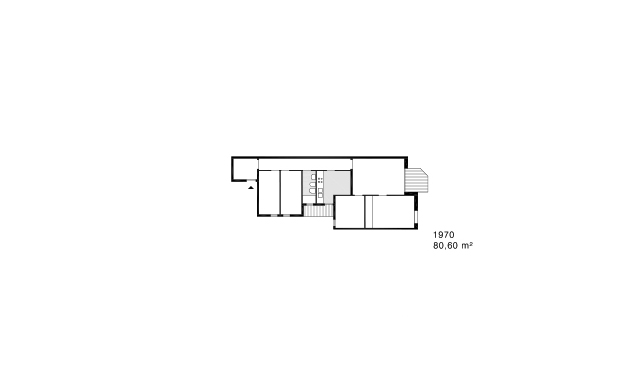

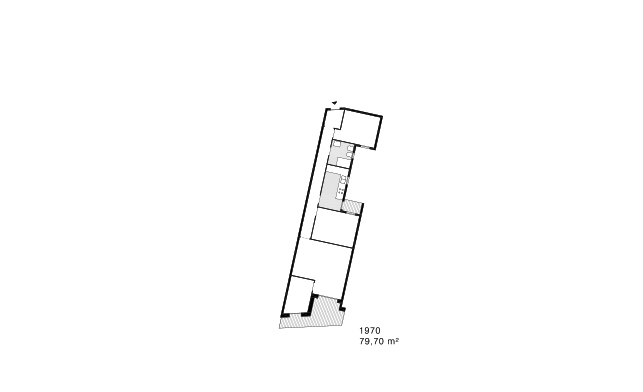

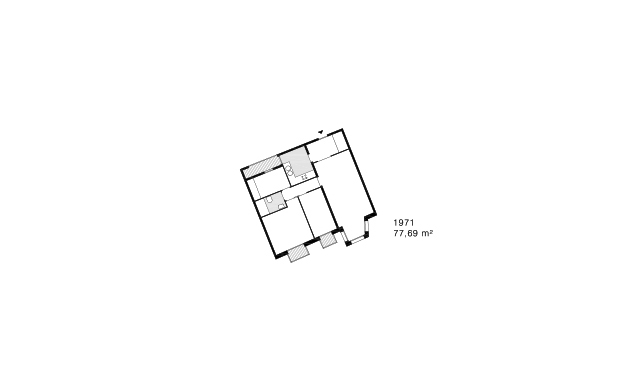

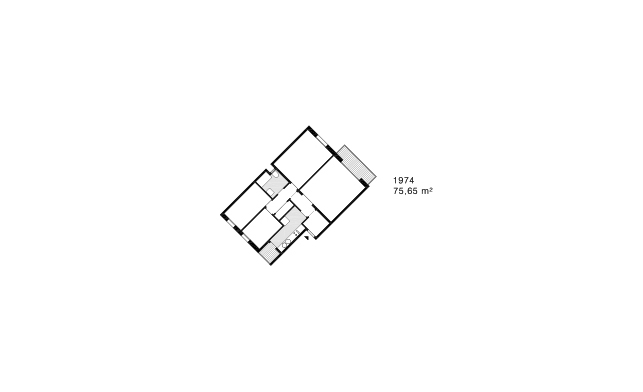

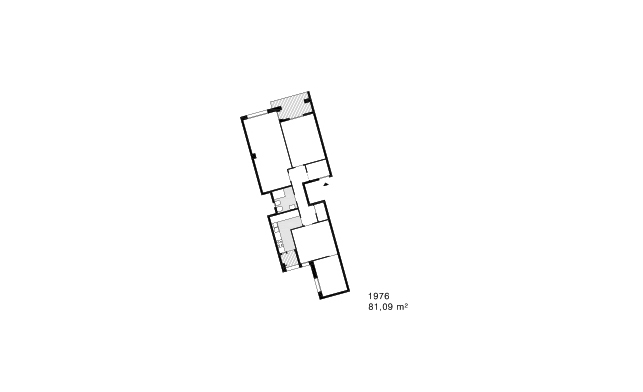

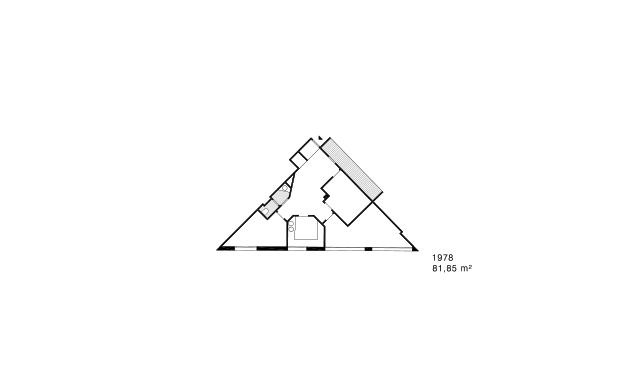

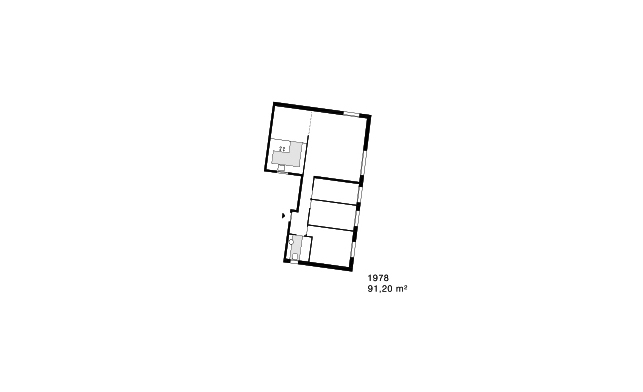

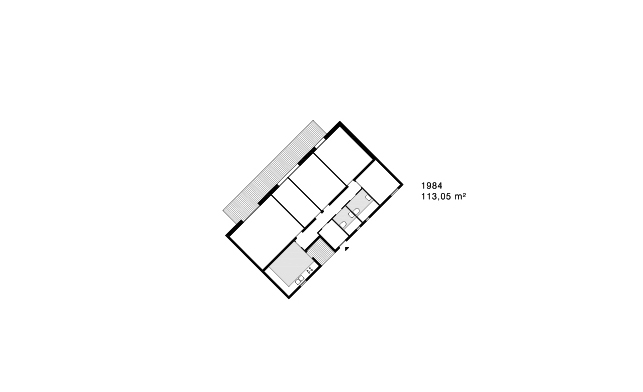

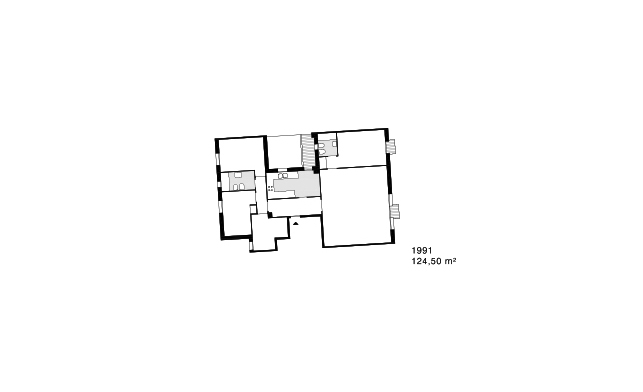

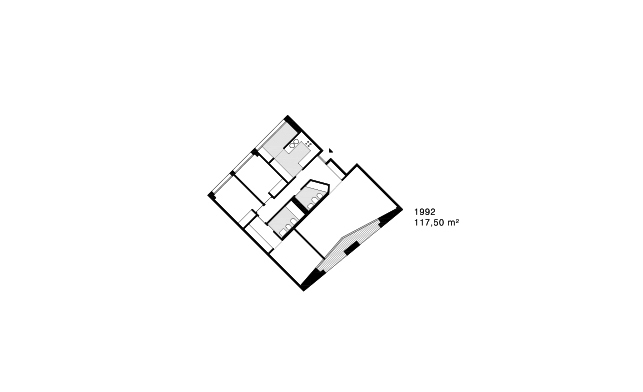

What follows is a compilation of 24 floorplans of existing dwellings in apartment buildings in the city of Barcelona.

All of them with the north up, all at the same scale.

All of them with the north up, all at the same scale.

Neither the name of the architect nor their precise location within the city are included.

They are ordered by year of construction and incorporate their built-up area.

They have not been chosen or selected in any way.

*They cover a period that goes from 1900 to 1992.

*They cover a period that goes from 1900 to 1992.

This is not a conscious choice, but it nevertheless reflects a crucial period in the city, from the Modernist era up to the celebration of the Olympic Games.

This is not a conscious choice, but it nevertheless reflects a crucial period in the city, from the Modernist era up to the celebration of the Olympic Games.

We often fixate on exemplary architecture. We study it, we visit it.

We often fixate on exemplary architecture. We study it, we visit it.

Books are written about it.It is architecture that serves as a desirable model to follow.

In doing this we fail to acknowledge that most buildings that give form to the city are not exemplary.

In doing this we fail to acknowledge that most buildings that give form to the city are not exemplary.

What is common is necessarily never extraordinary.

What is common is necessarily never extraordinary.

Even as if sometimes the sum of ordinary parts can create an extraordinary whole.

If the city is largely characterized by collective housing, this collection of drawings offers an objective, though incomplete, portrait of the primary elements that form the city. Each and every one is defined by its belonging to Barcelona, and each and every one contributes to the form of Barcelona.

Each and every one is defined by its belonging to Barcelona, and each and every one contributes to the form of Barcelona. This intertwined relationship is a product of time and space; of the geographical, morphological, historical and economic aspects that define the city.

This intertwined relationship is a product of time and space; of the geographical, morphological, historical and economic aspects that define the city.

1.The city

In its origin, urban fabric can be either spontaneously created or rationally planned.

The city of Barcelona, geographically limited by the sea, the mountains and two rivers, is a dense ensemble of old quarters –highly compacted urban structures characterized by amorphous blocks and narrow streets–, and the more recent expansions built in between and beyond, most notably the enlargement of the old center projected by Ildefons Cerdà.

Cerdà shares with Leonardo the aim to reach an ideal urban planning through the study of science, thus relegating the divine. **

In contraposition with the Gothic quarter, his proposal is based on a low-density non-hierarchical grid with its corners cut off, a 45-degree rotation from the north-south axis and the large size of its blocks, of 113m long per side. It is democratic in its homogeneity and forward thinking in its communication system.

Not unlike the Paris of Haussmann, a project that precedes Cerdà’s by only six years, it is a plan that represents a progressive impulse and an aim to improve the quality of housing and living in the wake of the industrialization of the city.

Cerdà’s plan proves to be extremely rational in its organization, but has proven to be partly utopian in its realization, as the built volume nowadays quadruples what was originally intended.

The result is a highly densified ensemble, not devoid of its own appeal, but which does not ultimately solve the housing problem by itself.

2.The city on the house

2.The city on the house

The city of Barcelona, whatever the area, is mainly formed by large enclosed blocks with buildings attached one to another. As a consequence of the relatively narrow land division, buildings become very deep, so as to occupy the maximum land possible.

To provide natural light and ventilation to these deep floorplans, small courtyards generally appear and service areas and secondary rooms gather around them. The climate and sun conditions of the city allow for this to function, but it also relates to the dominant catholic morals of introversion, of hiding more than showing off.

Three main dwelling typologies emerge:

- Double-oriented apartments, with façades to both the street and the interior courtyard, often characterized by narrow layouts and long corridors.

- Apartments with only one façade, either towards the street or to the inner courtyard.

- Apartments in corner buildings, with two consecutive façades towards the street.

3. The house on the city

3. The house on the city

The morphology and particular attributes of these apartments have a direct impact on the form of the city.

17 out of the 24 apartments were built between 1954 and 1979, none were built between 1936 and 1953. This is significant, as it directly relates to the history of the city and the country.

In 1936 the Spanish Civil War started, which would go on until 1939. The climate of extreme poverty and uncertainty that followed was a direct cause of the low construction.Only from 1953 on, with the end of the dictatorship’s self-imposed autarchy and the arrival of international funds to the country, the economy started to grow and the shortage of housing was alleviated as construction works intensified. As a result, a great part of the city is defined by the architecture of those decades.

The practical absence of dwellings on the ground floors enables the occupation of these spaces with shops, bars, ateliers or garages; thus creating a decentralized urban fabric of mixed-use activities and lively streets.

The overwhelming presence of balconies adds a flair of customizable domesticity to the image of the city, otherwise defined by rationally structured façades, often load-bearing, with vertically proportioned windows.

The balcony is an in-between space, the most public of all the private elements that conform an apartment in the collective housing and the expression of the individual self as part of the city, as seen by the proliferation of protest flags and banners, especially in the last few years.

The house

Taken out of their urban context, these drawings represent a miscellany of housing typologies. They epitomize the evolution of the housing typology in the 20th century, or its lack thereof.

Despite the development of radical theories on the architecture of housing, most of them translated into reality at some point or another with various levels of success, we must conclude that in terms of the reality of where people live, this evolution is far from groundbreaking.

The city and its architecture are in constant change, while at the same time they evolve very slowly. Architecture is made to last, but it is at the same time a highly adaptable environment. We may live in one-hundred-year-old homes built in two-thousand-year-old cities, and still live in the present.