Post-Critical Urbanism

Philippe Rahm

CHAPTER III: THE INDIVIDUALITY OF URBAN ARTIFACTS, ARCHITECTURE Architecture as Science When the villager had to get water from the village square fountain or food from the market place, social and political life was born in the city. Villagers didn’t arbitrarily choose to gather for a chat in open spaces, outside the shelter of […]

CHAPTER III: THE INDIVIDUALITY OF URBAN ARTIFACTS, ARCHITECTURE

Architecture as Science

When the villager had to get water from the village square fountain or food from the market place, social and political life was born in the city. Villagers didn’t arbitrarily choose to gather for a chat in open spaces, outside the shelter of their homes. Similarly, the arcade was invented to protect inhabitants from snow or sun. The air pollution in 19th century cities gave rise to boulevards for ventilation, which, consequently, caused new social behaviors like strolling. These fundamental causes of urban design were ignored during the 20th century thanks to the enormous use of energy by pumps, motors, fridge, heating systems and air conditioning, which cause today’s greenhouse effect.

Overcoming the legacies of energy, food and climatic constraints, urban theory from the 1970s, like Aldo Rossi’s Tendenza and American Pop art, lead to cities that have been designed in response to only social and cultural values, which are really the effects of urban form rather than its causes. Out of this came a tendency for urban designers and architects to use a morpho-typological analysis of the city, wherein they study and repeat more or less precisely the formal drawing and figurative language of the city in its current state, regardless of climate or physiological necessity.

Following this logic, the designers of urban form sought to understand the “spirit of place”, its formal and material identity, and to establish a plastic and cultural language – making use of a grammar based on semantic reference, analogy, allusion, and narration — which propagates more or less deviance, irony, and nostalgia. This analytical method slowly emerged in the 1960s as an architectural extension of the critical philosophical theories proposed as a response to the disaster of World War II (1939-45) such as Adorno and Horkheimer’s critical theory coming from the Frankfurt School or Foucault’s postmodernism in France, deeply disillusioned by the progressive and scientific objectives of the modernity of the early 20th century.

Modernity began, full of hope, as a mechanism through which mankind could progress and find happiness. It ended with the bloodshed of World War II and the atomic bomb. From the late 1960s, Critical Theories have denounced philosophers’ ideas of progress — technical, scientific, or architectural — accusing them of being responsible for the world’s disasters. The Critical Theories in architecture instead favored linguistic and semantic analysis that evolved from the post-modern economical affluence of the end of the 20 century and tourism development, a perfect match.

We have seen in recent years the exhaustion of critical methods which actually had the effect of stifling architectural invention with repetition and formalism. By banishing the scientific and medical tools, they had focus only on the narrative and plastic discourse, choosing the subjective over the objective, and obscuring the physiological and climatic causes of urbanization. These methodologies, however, lack the tools and theory to adequately address the very immediate issues of global warming and dwindling natural resources.. How to answer by irony to the Global warming? Why to tell a story on the depletion of resources instead of fighting it? We think today that science is not the cause of the catastrophes of the 20th century but it was his use in a univocal political way without accepting difference, alterity and multiplicity, that was the cause.

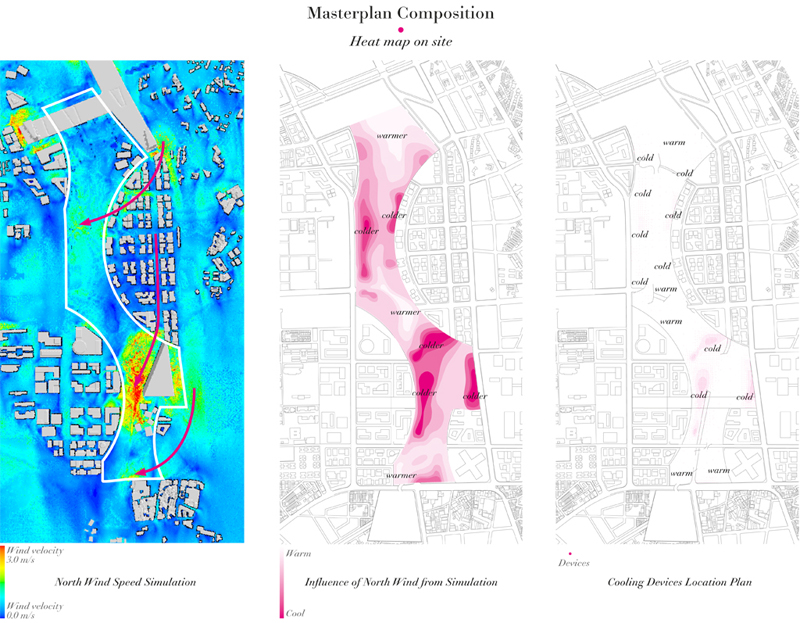

Our position is in no way a return to genesis of our modernity, but rather a generation of a new phase of architectural history that is post-post-modern, or maybe “post-critical”, as defined Hal Foster in his essay “Post-Critical” 1. We want to reengage physiology and meteorology as new tools for the urban and architectural design, in thinking critically by welcoming the multiplicity, diversity, and alterity of spaces and atmospheres, embracing the comfortable and uncomfortable, hot and cold, good and bad, wet and dry, clean and polluted, and the gradations between these extremes, to allow the user the freedom to use and interpret spaces in order to ensure his or her free will.

We want to abandon the modern univocal vision of space. We do not want to design uniform atmospheres that would only provide so-called perfect climates, because we also want the free choice for everybody between colder or warmer spaces, sunny or cloudy, clean or polluted. In this sense, we are the heirs of critical thinking, and not the neo-modern. Our goal is to re-engage science, medicine and technology with critical thinking, and to expand the toolset of critical thinking to include medical tools and physiological analyses. Our design brings variety of atmospheres and diversity of situations into the outdoor and indoor spaces, abandoning the so-called perfect and the univocal controlled modern architecture, keeping the field of the architectural design as open as possible, diversified, multiple, by accepting and designing either so-called good and less good places. Thus, the future of architecture and urbanism is post-critical.

We need to reengage the basic physiological and climatic necessities of the contemporary world in order to invent a new urban language, new forms, urban spaces to address these needs and raise new political, social, and cultural behaviors.