Madrid, Moneo and the complexity of urban artifacts

Alejandro Valdivieso

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS The Complexity of Urban Artifacts Rafael Moneo (born in Tudela, Navarra, 1937) has lived and works in Madrid since 1954, when he moved from the small city in the north of Spain where he spent his childhood and early youth to begin his university education. Since then, […]

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS

The Complexity of Urban Artifacts

Rafael Moneo (born in Tudela, Navarra, 1937) has lived and works in Madrid since 1954, when he moved from the small city in the north of Spain where he spent his childhood and early youth to begin his university education. Since then, short time periods have suspended his attachment to Madrid, a city that becomes crucial when one begins to investigate Moneo’s body of work. After qualifying as an architect in 1961, Moneo moved to Hellebaek in Denmark to work for Jørn Utzon. He returned to Madrid a year later for a short stay before moving to Rome, where he spent two years at the Spanish Academy, a wilful period to reflect upon theory and history and the place where he would establish his first linkages with the Italian scenario. In Rome he met Manfredo Tafuri, Paolo Portoghesi, Bruno Zevi (1) and Rudolf Wittkower, amongst other Italian architects and historians. It was not until 1967, back in Spain, where he met Aldo Rossi for the first time in one of the encounters organised by members of the Schools of Barcelona and Madrid, named as the Pequeños Congresos (“small conferences”).

Rossi’´s The architecture of the City was immediately translated into Spanish and published by Barcelona-based editorial and publishing house Gustavo Gili in 1971 (2). Architect and professor Salvador Tarragó translated the book (3) and promoted at once the ‘`Rossian’´ magazine 2C Arquitectura de la Ciudad (4), publishing three issues on Rossi. Other publications from Barcelona played an important role as printed spaces committed to the endeavour of disseminating architectural theory, transforming their previous condition as mere descriptive elements of a more and more confusing urban reality, into spaces where this reality was discussed for transformation. They became vehicles through which a new consideration of the city as collective space of action would be conceived, engaging with Rossi’´s main statement as to consider the city – and every urban artefact – to be by it’s very nature, collective.

Moneo wrote a paper for 2C on Rossi in one of the aforementioned monographs (5). 2C was contemporaneous of another magazine published in Barcelona during the late 70s, Arquitecturas Bis, información gráfica de actualidad (6), of which Moneo was one of the founding members. One of the first contents Moneo wrote for AB was an essay on Rossi and Vittorio Gregotti (7), which introduced a larger investigation on the former’s work, including a discussion of the principles Rossi made explicit on his book. AB stood out from other magazines published in Spain partly due to its connections with several North American and Italian publications, such as Oppositions from New York and the Milanese Lotus. They practiced an ‘after-modern’ philosophical and historical self-consciousness that contributed to a breaking with the traditions of modernism: theory was understood as a form of practice in its own right. The publication in Oppositions of “Aldo Rossi: The Idea of Architecture and the Modena Cemetery” (8) translated Rossi’s ideology, and what was known as ‘architettura autonomia’ (9), to the North American intellectual environment. In 1985, when the last issue of AB was published, Moneo was already working as Chairman of the Department of Architecture at Harvard University and his role as active translator of Rossi’s ideas into North American academia was by then firmly established.

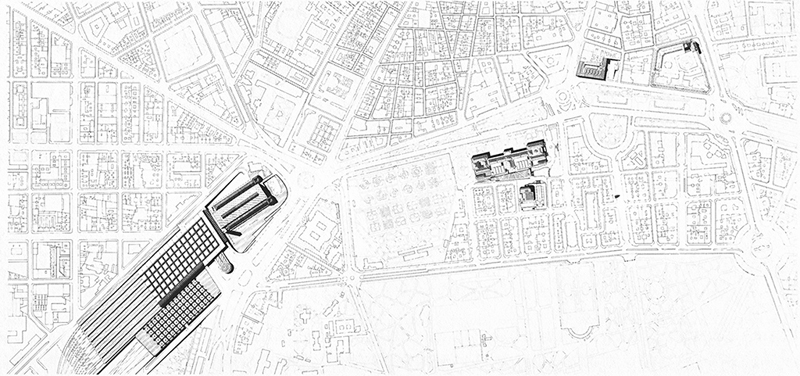

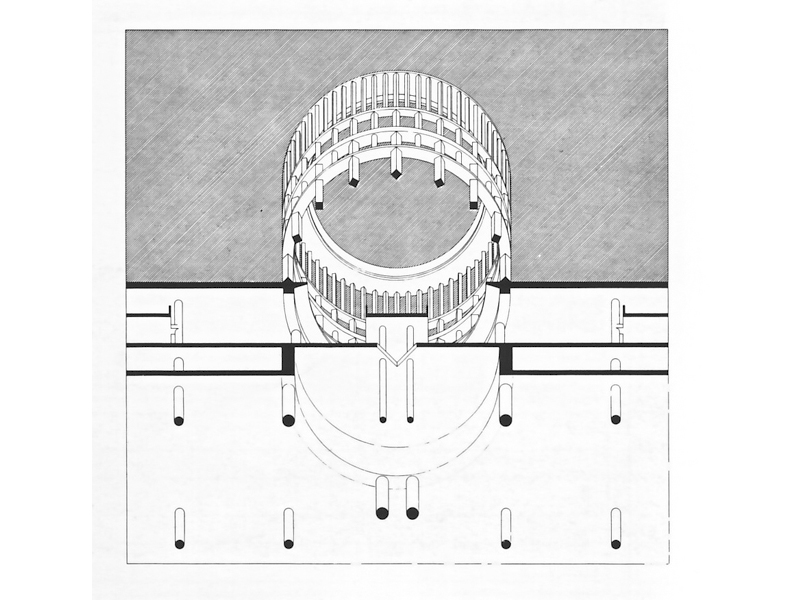

On his return to Spain, between 1991 and 1992 (10), Moneo was working on two projects in Madrid: the new Atocha Station (11) and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum (12). Both are purposefully and carefully redrawn in the city plan; together with the Bank of Spain (13) and the Prado Museum extensions (14). Atocha, which has recently been extended again, according to Moneo’s design, turns out to be the architecture capable of synthesising most accurately Moneo’s approach to what Rossi described as “the complexity of urban artefacts”. Its design strategy is the assertion of the concept of the city as a totality. The aim was to confer consistency, order and continuity to an urban complex comprising several different parts: the old station, with the preservation of its late nineteenth-century marquee; a new car park area just above the new suburban station; the intercity station, built around and defined according to the original alignment of tracks; and the intermodal transportation hub that manifests itself as the centerpiece of the architecture resolving Atocha’s complexity, as stated by Moneo (15). The hub reveals itself as a primary element, a permanent structure that ties together the complexity of all the overlapping layouts, movements and directions, but which above all determines and shapes the city. It also unveils what Rossi would describe as the contrast between private and universal, individual and collective, and emerges, like a metaphysical piece inside a painting by de Chirico, as a monument defined by Rossi standing within the landscape of Madrid. Moneo, as constructor of the city whose main intellectual vehicle is history – understood as the accumulation of human experience over time – was concerned with the notion of continuity and permanence, assuming that the city, as Rossi emphasised, endures through its transformations.

1 Moneo translated into Spanish Bruno Zevi´s 1964 edition of Architecture in Nuce [Architettura in nuce]. ZEVI, Bruno (1969) Arquitectura in Nuce. Una definición de arquitectura. Madrid: Aguilar.

2 Unlike in the United States, where the book was published more than a decade later: ROSSI, Aldo (1982) The Architecture of the City. Translation by Diane Ghirardo and Joan Ockman, and Introduction by Peter Eisenman; revised for the American edition by Aldo Rossi and Peter Eisenman. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

3 ROSSI, Aldo (1971). La arquitectura de la ciudad. Translation by Josep María Ferrer-Ferrer and Salvador Tarragó Cid. Colección “Arquitectura y Crítica”. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili.

4 2C Construcción de la Ciudad published a total of 22 issues from 1972 to 1985. Directed by Salvador Tarragó and Carlos Martí Arís.

5 MONEO, Rafael (1979). “La obra reciente de Aldo Rossi: dos reflexiones”. 2C Construcción de la Ciudad n. 14. December of 1979. Barcelona: Coop. Ind. De trabajo Asociado “Grupo 2C” S.C.I. Pages 38-39.

6 Arquitecturas Bis: información gráfica de actualidad was published in Barcelona from 1974 to 1985, editing a total of 52 issues. The magazine arranged a very efficient intern structure that actively participated in the production and edition of all the numbers, generating around 500 writings; about 30% of the total content (from news notes, theoretical and criticism writings, texts and book reviews). Under the direction of well-known publisher Rosa Regás, the editorial board was mainly made up by architects and professors – Oriol Bohigas, Federico Correa, Manuel de Solà-Morales, Rafael Moneo, Lluís Domènech, Helio Piñón, and Luis Peña Ganchegui (the latter a member since the 17-18 double issue published in July and September of 1977) – as well as the philosopher Tomás Lloréns and the graphic designer Enric Satué. From 1977, the architect Fernando Villavecchia joined as the Editorial Board secretary.

7 MONEO, Rafael (1974). “Rossi & Gregotti”. Arquitecturas Bis n. 4 (November 1974). Barcelona: La Gaya Ciencia.

8 “These notes, written in 1973 before the Triennale of 1974, do not deal with the complex notions which provoked that exhibition; with the grouping under the banner of the ‘Tendenza’ – a heterogeneous, yet consciously selected, group of architects from different countries. Thus these notes are limited to the discussion of Rossi’s principles made explicit in his book L´Architettura della Città, and in this light, to see how Rossi designed the Modena Cemetery without considering the propositions inherent in the Triennale even though Rossi was undoubtedly the inspiration for these ideas.” MONEO, Rafael (1976). Aldo Rossi: “The Idea of Architecture and the Modena Cemetery”. Oppositions n. 5. A Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture. Summer 1976. New York: Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies. [Original: MONEO, Rafael (1974) “La idea de Arquitectura en Rossi y el Cementerio de Modena”. Barcelona: Ediciones de la ETSAB].

9 […] “Moneo makes the connection between the two aspects inherent in Rossi’s work by breaking the article into two dialectic halves: each with its own theme and its own rhythm and cadence. The first part, which dissects Rossi’s thinking in his book The Architecture of the City, is more intense; the second part, which examines Rossi’s project for the Modena cemetery, is more lyrical. For me, this is architecture writing at its best – dense and informative, analytical and questioning. There is no question that Rossi’s metaphysics demand this kind of dissection. Equally important for the European context is the fact that such an article by Moneo, who was part of the Barcelona group of writers of the magazine Arquitecturas Bis, signals a possible change in the Milan/Barcelona axis: from the influence in the early sixties of Vittorio Gregotti and post-war functionalism to the new ideology present in Rossi’s work” […]. EISENMAN, Peter (1976) Prologue to Moneo’s text “The Idea of Architecture and the Modena Cemetery”. Ibid.

10 During his professorship at the School of Barcelona, Moneo continue living and working in Madrid, commuting to Barcelona to teach every week. During this time he developed two important works: the Bankinter Building in Madrid (1972-76) and Logroño town hall (1973-81). During his years at Harvard, as Chair of the Department of Architecture, from 1985 to 1990, Moneo moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, with his family, and although he opened a small office in Massachusetts Avenue, near Harvard Square, the main office remained in Madrid.

11 Atocha Station extension, Madrid (1984-92). In collaboration with Emilio Tuñón. First prize winner in competition (1983). Phase I (1985-88): Suburban Station and Intermodal transportation hub. Phase II (1988-92): Intercity station and s. XIX marquee building (architect Alberto Del Palacio, 1894). Phase III (2008-2010): Extension of the intercity station.

12 Renovation of the Palace of Villahermosa: Museum Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. 1989-1992.

13 Bank of Spain extension (competition winner, 1978-80, built in 2004-06).

14 Prado Museum extension (first prize in competition 1998, 1998-07).

15 MONEO, Rafael (2010). El Croquis n.20+64+98: Rafael Moneo: imperative anthology, 1967-2004. El Escorial, Madrid: El Croquis Editorial, p. 206-223.