Le Corbusier’s raised arm gestures a backstroke

Ala Younis

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS The Urban Artifact as a Work of Art In his first visit to Baghdad in 1957, Le Corbusier asked Iraq’s Director of Physical Education: “A swimming pool with waves?” Enthusiasm over a pool with artificial waves was stoked by their mutual interest in aqua sports. What Le […]

CHAPTER I: THE STRUCTURE OF URBAN ARTIFACTS

The Urban Artifact as a Work of Art

In his first visit to Baghdad in 1957, Le Corbusier asked Iraq’s Director of Physical Education: “A swimming pool with waves?” Enthusiasm over a pool with artificial waves was stoked by their mutual interest in aqua sports. What Le Corbusier and the Iraqis wanted for the Sport Center was a structure that would embody a modern Mesopotamia whose architecture would feature waters channelled from the Tigris, and an artificial wave pool collected from its flow. From now on, planning Baghdad becomes a strategy, an expression of power, or a necessity when it takes the form of enabling a future possibility.

In 1959, the Ministry of Public Works and Housing asked Le Corbusier: “What do you think about the creation of a second stadium in Baghdad?” He answered: “In principle it appears to me to be quite useless as it minimizes the one or the other by a sterile competition between them.” (1) Le Corbusier’s Saddam Hussein Gymnasium metamorphosed through numerous iterations of plans over a period of twenty-five years before it was finally inaugurated in 1980. Up until then, the commission passed through five military coups; six heads of state; four master plans, each with its own town planner; a Development Board that became a Ministry and then a State Commission; a modern starchitect among a constellation of many others with their associated architects, draftsmen, contractors, translators and lawyers; local architects accompanied by similar structures from their own consulting firms, from government departments and parallel commissions; more than one local artist/sculptor; eager competitors; and other monuments that appeared and disappeared as a result of these same conglomerations.

The Baghdad-based consulting firm Iraq Consult (1952–1978), led by its founder Rifat Chadirji (1926– ), facilitated the continuously interrupted process of building the gymnasium. In addition to his involvement in other aspects of the project, Chadirji took a set of 35mm photographs of the Gymnasium in 1982. These photographs and other documents of the urban artefacts he built exist now in the form of montages made up of scraps smuggled in and out of Abu Ghraib prison while Chadirji served part of a life sentence. The architect produced these compilations as he edited his notes into a massive monograph that renders the development of his architectural philosophy within the context of the modernity-identity discourse and his local and international commissions, and how these were affected by political conflict.

In December 2011, I asked the exiled architect about the parallel fates of the Gymnasium and its creators. From his response, it seemed to me that he revisited the enthusiasm that had driven the international architectural endeavours. At 85, he considered his work in introducing samples of international modernism was only for these projects to be experienced first-hand by the students and citizens of Baghdad. In another expression of dismay, he said that his buildings are being demolished one after another.

Chadirji’s first statement illustrated an interesting image of power relations in architecutre; to outsource architects to present structures on a platform for local viewers, removes any attributed or attempted locality and reduces the buildings to their basic relationship with their makers. The urban artefacts, in this image, become basic forms that aggregate, propagate, and negate forms of other structures. Perhaps this power relation is what Le Corbusier tried to explain when he responded to the question regarding a second stadium, or the fates Chadirji was refusing in his second statement.

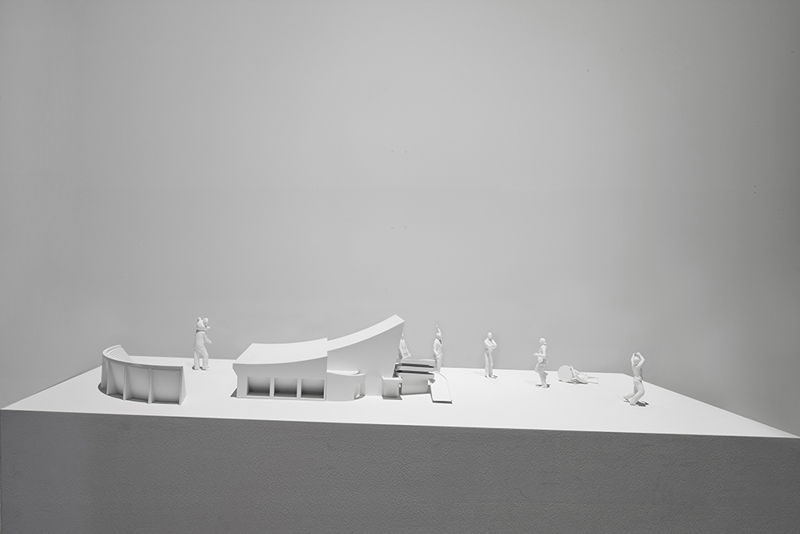

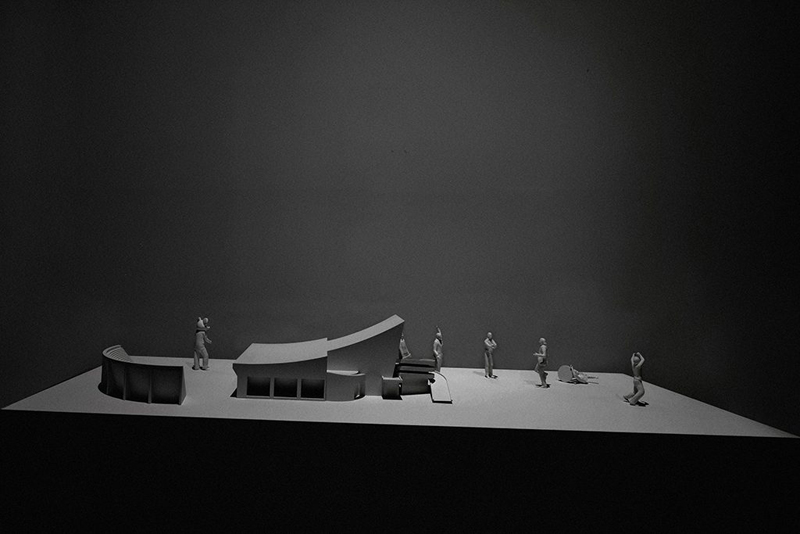

Le Corbusier created an image of such power relations in his model of the superstructures for his Cité radieuse in Marseille. On an inclined platform, he presented multiple architectural forms existing next to each other, the background was an image, and there were no other structures around nor beneath this presentation. Whether serving the residents of the main structure beneath (the building) or the city, in the images produced by Le Corbusier’s model and Chadirji statement, the buildings are meant to come to the foreground, emptied of all players. Between these forms and a sweeping landscape, two spaces remain: one of pure air permeating between the buildings, and an overall one containing space that surrounds the block of forms interchanging their power, in a secluded universe where nothing else exists.

“Plan for Greater Baghdad” is a project heavily based on archives, found images, and objects, that reproduce the story and politics around the Saddam Hussein Gymnasium project in the form of a timeline, an architectural model and a set of characters. The characters reproduce citations of imageless gestures that relate to performances of design, power, and designing power. They are retrieved as a set of motions and signals enacted by characters frozen in the denouements of historical time: Chadirji jogging in the courtyard of Abu Ghraib Prison or hurrying to photograph his monument before it is demolished; a young Saddam Hussein on the edges of the scene as monuments’ (de)constructor; and Le Corbusier raising his arm to gesture a backstroke of an artificial wave in a swimming pool to pull its waters from the Tigris. On an inclined base, an architectural model of the gymnasium is fixed next to, but different in proportion from, the set of characters. The set up aimed to looks at monuments, their architects, for governments, through the alternating power relations between them in the times of shifting states. In the diverse iterations of the project, these elements morph as they migrate within a universe of possible artistic and architectural intentions.

1 Report by Director General, Technical Section 2, Baghdad, titled “Baghdad Stadium, Notes: From Mr. Le Corbusier, Architect”, 4 May 1959.